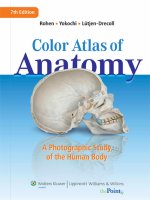

comprehensive vascular and endovascular surgery 2nd ed - j. hallett, et al., (mosby, 2009)

Bạn đang xem bản rút gọn của tài liệu. Xem và tải ngay bản đầy đủ của tài liệu tại đây (36.07 MB, 901 trang )

1600 John F. Kennedy Blvd.

Ste 1800

Philadelphia, PA 19103-2899

COMPREHENSIVE VASCULAR AND ENDOVASCULAR

SURGERY, SECOND EDITION ISBN: 978-0-323-05726-4

Copyright © 2009, 2004 by Mosby, Inc., an affiliate of Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Rights

Department: phone: (+1) 215 239 3804 (US) or (+44) 1865 843830 (UK); fax: (+44) 1865 853333; e-mail:

You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier website at

/>Notice

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden

our knowledge, changes in practice, treatment, and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate.

Readers are advised to check the most current information provided (i) on procedures featured or (ii) by

the manufacturer of each product to be administered, to verify the recommended dose or formula, the

method and duration of administration, and contraindications. It is the responsibility of the practitioner,

relying on their own experience and knowledge of the patient, to make diagnoses, to determine dosages and

the best treatment for each individual patient, and to take all appropriate safety precautions. To the fullest

extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the Editors assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to

persons or property arising out of or related to any use of the material contained in this book.

The Publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Comprehensive vascular and endovascular surgery/[edited by] John W. Hallett … [et al.]. 2nd ed.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-323-05726-4

1. Blood-vessels Surgery. 2. Blood-vessels Endoscopic surgery. I. Hallett, John W.

[DNLM: 1. Vascular Surgical Procedures. 2. Endoscopy methods. 3. Vascular Diseases surgery.

WG 170 C7377 2009]

RD598.5.C644 2009

617.4’130597 dc22 2009008603

Acquisitions Editor: Judith Fletcher

Developmental Editor: Lisa Barnes

Project Manager: Mary Stermel

Marketing Manager: Radha Mawrie

Printed in China

Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

v

DONALD T. BARIL, MD

Fellow, Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

GINGER BARTHEL, RN, MA, FACHE

Vice President, Clinical Operations

Advocate Lutheran General Hospital

Park Ridge, Illinois, USA

B. TIMOTHY BAXTER, MD

Professor

Department of Surgery

University of Nebraska

Omaha, Nebraska, USA

JONATHAN D. BEARD, FRCS, ChM, Med

Professor of Surgical Education

University of Sheffield

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Sheffield Vascular Institute

Northern General Hospital

Sheffield, United Kingdom

JEAN-PIERRE BECQUEMIN, MD, FRCS

Professor of Vascular Surgery

University of Paris XII

Head of the “Pole”

Cardiac Vascular and Thoracic

Henri Mondor Hospital

Creteil, France

MICHAEL BELKIN, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery

Harvard Medical School

Chief, Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

THOMAS C. BOWER, MD

Professor of Surgery

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Consultant

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

KEVIN G. BURNAND, MBBS, MS, FRCS

Professor, Academic Surgery

King’s College London

Professor, Academic Surgery

St. Thomas Hospital

London, United Kingdom

JAAP BUTH, MD, PhD

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

Catharina Hospital

Eind Hovem, The Netherlands

JOHN BYRNE, MCh FRCSI (GEN)

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

Albany Medical Center

Albany, New York, USA

RICHARD P. CAMBRIA, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Harvard Medical School

Chief, Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

CHRISTOPHER G. CARSTEN, MD

Assistant Program Director

Academic Department of Surgery

Greenville Hospital System University Medical Center

Greenville, South Carolina, USA

Contributors

Contributors

vi

KENNETH J. CHERRY Jr, MD

Head, Division of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

Professor of Surgery

Chair, Vascular Surgery

University of Virginia Hospital

Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

W. DARRIN CLOUSE, MD, FACS

Associate Professor of Surgery

The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Chief, Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

San Antonio Military Medical Center

San Antonio, Texas, USA

MARC COGGIA, MD

Professor of Vascular Surgery

Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines University

Versailles, France

Vascular Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

Ambroise Pare University Hospital

Boulogne-Billancourt, France

MATTHEW A. CORRIERE, MD

Fellow

Section on Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA

DAVID L. CULL, MD

Vice Chairman, Surgical Research

Academic Department of Surgery

Greenville Hospital System University Medical Center

Greenville, South Carolina, USA

PHILIPPE CUYPERS, MD, PhD

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

Catharina Hospital

Eindhovem, The Netherlands

MICHAEL D. DAKE, MD

Chairman

Department of Radiology

University of Virginia Health System

Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

ALUN H. DAVIES, MA, DM, FRCS, ILTM

Imperial College

Imperial Vascular Unit

Charing Cross Hospital

London, United Kingdom

MAGRUDER C. DONALDSON, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery

Harvard Medical School

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Chairman

Adjunct Staff

Department of Surgery

Metro West Medical Center

Framingham, Massachusetts, USA

Department of Surgery

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

JOSÉE DUBOIS, MD

Professor

Department of Radiology, Radio-Oncology, and Nuclear

Medicine

University of Montreal

Chair

Department of Medical Imaging

CHU Sainte-Justine

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

WALTER N DURÁN, PhD

Professor of Physiology and Surgery

Director, Program in Vascular Biology

Department of Pharmacology and Physiology

New Jersey Medical School

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Medical

School

Newark, New Jersey, USA

JONOTHAN J. EARNSHAW, DM, FRCS

Consultant Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

Gloucestershire Royal Hospital

Gloucestershire, United Kingdom

JAMES M. EDWARDS, MD

Professor of Surgery

Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Oregon Health and Science University

Department of Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

Portland, Oregon, USA

vii

Contributors

MATTHEW S. EDWARDS, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery

Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Wake Forest University Health Sciences

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center

Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA

JULIE FREISCHLAG, MD

Chair

Department of Surgery

Surgeon-in-Chief

Johns Hopkins Medical Institution

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

MARY E. GISWOLD, MD

Staff Surgeon

Kaiser Permanente

Sunnybrook Medical Office

Clackamas, Oregon, USA

PETER GLOVICZKI, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Chair

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Director

Gonda Vascular Center

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

OLIVIER GOËAU-BRISSONNIÈRE, MD, PhD

Professor of Vascular Surgery

Versailles Saint-Quentin-en–Yvelines University

Versailles, France

Head

Department of Vascular Surgery

Ambroise Pare University Hospital

Boulogne-Billancourt, France

MANJ S. GOHEL, MD, MRCS

Honorary Research Fellow

Faculty of Medicine

Imperial College London

Specialist Registrar

Department of Vascular Surgery

Charing Cross Hospital

London, United Kingdom

BRUCE H. GRAY, DO

GHS Clinical Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

Medical University of South Carolina

Director of Endovascular Services

Department of Vascular Surgery

Greenville, South Carolina, USA

MARCELO GUIMARAES, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Radiology—Heart and Vascular Center

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina, USA

MAHER HAMISH, MD, FRCS

Senior Clinical Fellow

Imperial Vascular Unit

Charing Cross Hospital

London, United Kingdom

KIMBERLEY J. HANSEN, MD

Professor of Surgery and Section Head

Section of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Division of Surgical Sciences

Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA

PAUL N. HARDEN, MB, ChB, FRCP

Consultant Nephrologist

Oxford Kidney Unit

The Churchill Hospital

Oxford, United Kingdom

JOHANNA M. HENDRIKS, MD, PhD

Consultant

Department of Vascular Surgery

Erasmus University

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

NORMAN R. HERTZER, MD, FACS

Emeritus Chairman

Department of Vascular Surgery

The Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio, USA

Contributors

viii

WALTER HUDA, PhD

Professor

Department of Radiology

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina, USA

GLENN C. HUNTER, MD

Staff Surgeon

Department of Surgery

Tucson Medical Center

Tucson, Arizona, USA

DANIEL M. IHNAT, MD, FACS

Assistant Professor of Clinical Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona, USA

JEFFREY A. KALISH, MD

Clinical Fellow in Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

MANJU KALRA, MBBS

Associate Professor of Surgery

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Mayo Clinic

Consultant

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

EDOUARD KIEFFER, MD

Professor of Vascular Surgery and Chief

Department of Vascular Surgery

Pitie-Salpetriere University Hospital

Paris, France

CONSTANTINOS KYRIAKIDES, MD, FRCS

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Department of Surgery

Barts and the London NHS Trust

The Royal London Hospital

Whitechapel, London, United Kingdom

FRANK A. LEDERLE, MD

Professor of Medicine

Veteran Affairs Medical Center

Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

LUIS R. LEON Jr, MD, RVT, FACS

Chief of Vascular Surgery

Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Southern Arizona Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Associate Professor of Surgery

Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

University of Arizona Medical Center

Tucson, Arizona, USA

BENJAMIN LINDSEY, MB BS, FRCSE

Department of Vascular Surgery

Royal Cornwall Hospital

Cornwall, United Kingdom

NICK J.M. LONDON, MD, FRCS, FRCP

Professor of Surgery

Vascular Surgery Group

University of Leicester

Hon. Consultant Vascular/Endocrine Surgeon

Vascular Surgery

UHoL, Leicester Royal Infirmary

Leicester, United Kingdom

WILLIAM C. MACKEY, MD, FACS

Andrews Professor and Chairman

Department of Surgery

Tufts University School of Medicine

Surgeon-in-Chief

Tufts New England Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

JASON MacTAGGART, MD

Fellow in Vascular Surgery

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, California, USA

JOVAN N. MARKOVIC, MD

Postdoctorate

Department of Surgery

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina, USA

CATHARINE L. McGUINNESS, MS, FRCS

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Royal Surrey County Hospital

Guildford, Surrey, United Kingdom

ix

Contributors

MARK H. MEISSNER, MD

Professor

Department of Surgery

University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, Washington, USA

MATTHEW T. MENARD, MD

Instructor in Surgery

Harvard Medical School

Co-Director, Endovascular Surgery

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

VIRGINIA M. MILLER, PhD

Professor

Departments of Surgery and Physiology and Biomedical

Engineering

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

JOSEPH L. MILLS Sr, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Arizona Health Sciences Center

Chief of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

University Medical Center

Tucson, Arizona, USA

GREGORY L. MONETA, MD

Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

Oregon Health and Science University

Chief of Vascular Surgery

Oregon Health and Science University Hospital

Portland Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital

Portland, Oregon, USA, USA

JONATHAN G. MOSS, MBChB, FRCS, FRCR

Professor of Interventional Radiology

University of Glasgow

North Glasgow University Hospitals

Glasgow Scotland, United Kingdom

JOSEPH J. NAOUM, MD

Division of Vascular Surgery

The Methodist Hospital

Cardiovascular Surgery Associates

Houston, Texas, USA, USA

A. ROSS NAYLOR, MBChB, MD, FRCS

Professor of Vascular Surgery

Department of Vascular Surgery

Leicester Royal Infirmary

Leicester, United Kingdom

GUSTAVO S. ODERICH, MD

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Consultant

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

PATRICK J. O’HARA, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

Staff Vascular Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

The Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Cleveland, Ohio, USA, USA

VINCENT L. OLIVA, MD

Professor of Radiology

Department of RadiologyRadiology

University of Montreal

Assistant Chief

Department of RadiologyRadiology

Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montreal

Chief of Vascular and Interventional Radiology Division

Department of RadiologyRadiology

Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montreal

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

FRANK PADBERG Jr, MD

Professor of Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

New Jersey Medical School

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

Attending Vascular Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

University Hospital

Newark, New Jersey, USA

Chief, Section of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

Veterans Affairs, New Jersey Health Care System

East Orange, New Jersey, USA

Contributors

x

LUIGI PASCARELLA, MD

Resident

Department of Surgery

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina, USA

FRANK B. POMPOSELLI Jr, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery

Harvard Medical School

Chief of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

BRENDON QUINN, MD

Vascular Fellow

Academic Department of Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

Greenville Hospital System University Medical Center

Greenville, South Carolina, USA

TODD E. RASMUSSEN, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery

Norman M. Rich Department of Surgery

The Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Chief, San Antonio Military Vascular Surgery

Wilford Hall United States Air Force Medical Center

Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, USA

Chief, San Antonio Military Vascular Surgery

Brooke Army Medical Center

Fort Sam Houston, Texas, USA

JOHN E. RECTENWALD, MD

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

AMY B. REED, MD

Director, Vascular Surgery Fellowship

Division of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

Staff Vascular Surgeon

University Hospital

Department of Surgery

Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

LINDA M. REILLY, MD

Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery—Vascular Division

University of California, San Francisco

Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of California, San Francisco Medical Center

Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

San Francisco VA Medical Center

San Francisco, California, USA, USA

ROBERT Y. RHEE, MD

Clinical Director

Division of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, USA

JEFFREY M. RHODES, MD

Attending Physician

Department of Vascular Surgery

Rochester General Hospital

Rochester, New York, USA, USA

JOSEPH J. RICOTTA II, MD

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Consultant

Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota, USA, USA

DAVID RIGBERG, MD

Assistant Professor of Surgery

Division of Vascular Surgery

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California, USA, USA

CLAUDIO SCHÖNHOLZ, MD

Professor of Radiology

Radiology Heart and Vascular Center

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina, USA, USA

xi

Contributors

PARITOSH SHARMA, MRCS

Vascular Research Fellow

Department of Surgery

Barts and the London NHS Trust

The Royal London Hospital

Whitechapel, London, United Kingdom

AMANDA SHEPHERD, MRCS

Doctor

Imperial Vascular Unit

Imperial College

London, United Kingdom

CYNTHIA SHORTELL, MD, FACS

Professor of Surgery

Chief of Vascular Surgery

Program Director, Vascular Residency

Division of Surgery

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, North Carolina, USA, USA

FRANK C.T. SMITH, BSc, MD, FRCS

Reader and Consultant Vascular Surgeon

University of Bristol

Bristol Royal Infirmary

Bristol, United Kingdom

GILLES SOULEZ, MD, MSc

Professor

Department of Radiology

University de Montreal

Interventional Radiologist, Director of Research

Department of Radiology

Centre Hospitalier de l’Universite de Montreal

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

JAMES C. STANLEY, MD

Professor of Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Michigan Medical School

Director

Cardiovascular Center

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, USA

KONG TENG TAN, MD

Assistant Professor of Radiology

Interventional Radiology

University of Toronto

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

DESAROM TESO, MD

Fellow in Vascular Surgery

Section of Vascular Surgery

Tufts Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts, USA, USA

STEPHEN C. TEXTOR, MD

Professor of Medicine

Departments of Nephrology and Hypertension

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Consultant

Departments of Nephrology and Hypertension

Rochester Methodist Hospital

Consultant

Saint Mary’s Hospital

Rochester, Minnesota, USA

BRAD H. THOMPSON, MD

Associate Professor of Radiology

Department of Radiology

Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine

Department of Radiology

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

Iowa City, Iowa, USA, USA

RENAN UFLACKER, MD

Professor of Radiology

Department of Radiology—Heart and Vascular Center

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina, USA, USA

GILBERT R. UPCHURCH Jr, MD

Professor of Surgery

Section of Vascular Surgery

Department of Surgery

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, USA

EDWIN J.R. VAN BEEK, MD, PhD

Professor of Radiology, Medicine, and Biomedical

Engineering

Department of Radiology

Carver College of Medicine

Iowa City, Iowa, USA, USA

Contributors

xii

MARC R.H.M. VAN SAMBEEK, MD, PhD

Associate Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

Erasmus University

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Consultant Vascular Surgeon

Department of Vascular Surgery

Catharina Hospital

Eindhovem, The Netherlands

FRANK C. VANDY, MD

Resident

Department of Vascular Surgery

University of Michigan Medical Center

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, USA

DIERK VORWERK, MD

Professor

Department of Radiology

University of Technology

Chairman

Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology

Klinikum Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt, Germany

THOMAS W. WAKEFIELD, MD

S. Martin Lindeanuer Professor of Vascular Surgery

Section Head

Department of Vascular Surgery

University of Michigan Medical Center

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, USA

NICOLE WHEELER, MD

Vascular Surgery Bidwell Fellow

Oregon Health and Science University

Portland, Oregon, USA

JOHN V. WHITE, MD

Clinical Professor

Department of Surgery

University of Illinois

Chicago, Illinois, USA

Chairman

Department of Surgery

Advocate Lutheran General Hospital

Park Ridge, Illinois, USA

CHRISTOPHER L. WIXON, MD, FACS

Assistant Professor of Surgery and Radiology

Mercer University School of Medicine

Director and Chairman

Department of Cardiovascular Medicine and Surgery

Memorial Health University Medical Center

Savannah, Georgia, USA

KENNETH R. WOODBURN, MB ChB,

MD FRCSG (GEN)

Honorary University Fellow

Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry

University of Plymouth

Plymouth, United Kingdom

Consultant Vascular and Endovascular Surgeon

Vascular Unit

Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust

Truro, Cornwall, United Kingdom

KENNETH J. WOODSIDE, MD

Clinical Lecturer in Surgery

Division of Transplantation

Department of Surgery

University of Michigan Health System

Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, USA

xiii

Something happens with the first edition of a textbook that leads to a second edition. Something must have succeeded. Someone

has to understand the success to ensure that the next edition meets the expectations of the readers. As we planned this new edition

of Comprehensive Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, the original four editors and our editorial staff discussed that “something”

in great detail.

What have we heard about the first edition that sets this textbook apart from others? First, we chose a comprehensive but

concise approach to cover all the main topics in vascular disease. Detailed discussions of rare topics were left to other, more ency-

clopedic, books. In other words, our readers commented that they could read this textbook cover-to-cover in a reasonable period

of time. Second, we chose authors who are clinical experts in both open surgical and endovascular techniques. Consequently, the

first edition revealed a balance in open and endovascular options for every clinical problem.

Some other features of the first textbook appealed to our readers, too. The consistency in simply designed anatomical drawings

and reproductions of vascular imaging was considered a strength. Next, and perhaps as important, the CD-ROM collection of all

illustrations and tables helped our readers to quickly assemble PowerPoint presentations for teaching. This innovation with the

book may have done more to advance vascular disease education than any other feature of the first edition.

This newest edition of Comprehensive Vascular and Endovascular Surgery sustains the features that our readers acknowledged

so graciously with the first textbook. With this edition, all of the text, illustrations, and study questions will be available on a spe-

cial website. In other words, you will have the textbook at your fingertips on the Internet at any location where you may need to

refresh your knowledge or prepare a PowerPoint presentation. In addition, we have advanced this new edition with several new

features. First, Dr Thom Rooke, an internationally recognized cardiovascular medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic, joins our

editorial team. We recognize that cardiologists and vascular internists are venturing more into medical and interventional man-

agement of peripheral vascular disease. Dr Rooke’s input represents their interests. Second, we have updated every chapter and

added several new erudite discussions of other topics, such as vascular imaging and radiation safety, vascular infections, and aor-

tic dissections. Finally, we have added a bank of study questions to assist with review and preparation for board examinations.

We hope that this second edition of Comprehensive Vascular and Endovascular Surgery provides a practical and user-friendly

reference for the care of your patients. Again, we welcome your feedback to improve future editions. Stay in touch. Share your

experience and knowledge with us and with your colleagues who are dedicated to vascular care.

John (Jeb) Hallett

Joseph Mills

Jonothan Earnshaw

Jim Reekers

Thom Rooke

Preface

3

1

Historical Perspectives

in Vascular Surgery: The

Evolution of Modern

Trends

Todd E. Rasmussen, MD • Kenneth J. Cherry Jr., MD

Key Points

• Military vascular surgery

• The beginnings of aortic surgery

• Peripheral arterial reconstruction

• Aortic thromboendarterectomy

• Development of aortic prostheses

• Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms

and aortic dissections

• Mesenteric occlusive disease

• Carotid arterial reconstruction

• Evolution of endovascular procedures

• Conclusion

This chapter focuses on the evolution of

interesting and important trends in the

history of vascular surgery and endo-

vascular therapy. We emphasize that a

comprehensive history of vascular sur-

gery is beyond the scope of this chapter

for several reasons. Foremost, attempts

to account for all of the contributions of

Antyllus, Paré, Lambert, Eck, Murphy, the Hunters, Cooper,

Mott, Matas, Halstead, Carrel, Exner, Goyanes, and other

pioneers of surgery and medicine would fail to do them jus-

tice. Furthermore, a comprehensive and modern historical

account would incorporate the contributions of transplant

and cardiovascular surgery, venous surgery, vascular medi-

cine and pharmacology, diagnostic and therapeutic radiology,

and noninvasive vascular testing. Such breadth would surely

require more text than the editors are willing to spare.

Consequently, this chapter represents not a complete his-

tory of vascular surgery but rather a selective perspective—a

perspective of those people and advances of the modern era

that have sparked or perpetuated an evolution of vascular care.

The omission of certain surgeons and reports may dismay

some readers, and the inclusion of others will undoubtedly

cause similar discord. Other interpretations and appraisals of

our history are as valid as this one; therefore, this effort can be

seen as a starting point for collegial discussion.

MILITARY VASCULAR SURGERY

Hippocrates is credited with the phrase “He who wishes to be a

surgeon should go to war.” Consequently, no history of vascu-

lar surgery would be complete without examination of the con-

tributions made by military surgeons. This notion is especially

relevant today with the global war on terror in Afghanistan and

Iraq. These conflicts have provided the environment in which

advances in vascular and endovascular surgery are being made

under the most challenging conditions and with the most dev-

astating injuries seen since the Vietnam War. Claudius Galen,

one of the greatest surgeons of antiquity, was known for his

treatment of traumatic wounds.

1

As a surgeon to the gladia-

tors of the second century, he cared for orthopedic, abdomi-

nal, and vascular injuries using sutures, dressings, and splints.

The use of heat or cautery was paramount in the treatment

of bleeding at the time and was often achieved using boiling

oil.

2

In the sixteenth century, the French physician Ambrose

Paré advocated a method other than cautery to control hem-

orrhage. Specifically, Paré introduced the ligature for control

of bleeding in a battle in which he had exhausted the supply

SECTION I Background

4

of boiling oil.

2

Ligation of vascular injuries as documented by

Paré would remain the treatment of choice until 1952.

Another French surgeon, Dominique Jean Larrey, was the

surgeon-in-chief of the Napoleonic armies (1797 to 1815)

and is widely regarded as the first modern military surgeon.

Larrey’s greatest contribution was the “flying ambulance,”

which was a horse-drawn vehicle designed to transport

wounded soldiers from the battlefield to hospitals in the rear

for surgical care. Larrey’s legacy of rapid casualty movement

was fully realized nearly 150 years later when use of helicopters

was implemented during the Korean War.

World War I

During World War I, George Makins, the British surgeon gen-

eral, reported great experience with the treatment of vascular

injuries in his paper “On Gunshot Injuries of the Blood Ves-

sels.”

3

In this report, Makins reviewed more than 1000 vascu-

lar injuries and described the preferred treatment as ligation. In

contrast, the German surgeon Jaeger began attempts to repair,

instead of ligate, arterial injuries in an effort to avoid amputa-

tion.

1,4

The German literature reported successful vascular

repairs during World War I. Unfortunately, these successes were

largely ignored, and enthusiasm for arterial repair waned.

World War II

Despite improvements in mobile surgical units, antibiot-

ics, and whole blood transfusions, World War II did little to

advance the treatment of battlefield vascular injuries beyond

the principle of ligation. In their classic review of nearly 2500

cases of arterial wounds treated in World War II, Michael

DeBakey and Fiorindo Simeone found only 81 instances of

suture repair.

5

The amputation rate in this “highly selective

group” of patients with “minimal wounds” was 36%, as com-

pared with an amputation rate of 49% following ligation. The

poor results of vascular repair led the authors to acknowledge

that ligation of vascular injury during wartime was “one of

necessity,” although repair would be ideal. The major obsta-

cle to vascular repair was prolonged evacuation time, which

averaged more than 10 hours, practically precluding success-

ful arterial repair and limb salvage.

4,5

Although the concept

of bringing the surgeon close to the battlefield was explored,

it was considered unworkable to provide definitive operative

care of vascular injuries at forward echelons.

Korean War

Following World War II, military doctrine prohibited

attempts at vascular repair in the battlefield, although a

program to explore this possibility was initiated at Walter

Reed Army Hospital in 1949. At the onset of the Korean

War, a U.S. Navy surgeon, Frank C. Spencer, was deployed

with “Easy Medical Company,” a unit of the First Marine

Division (Figure 1-1).

6

In 1952, Spencer challenged war-

fare doctrine mandating ligation and repaired an arterial

injury with a cadaveric femoral artery (i.e., arterial homo-

graft). The Pentagon sent Army surgeons to verify Spen-

cer’s achievements, which were eventually reported in

1955. Col. Carl Hughes visited Spencer in Korea and not

only verified his clinical experience but also aided in the

delivery of badly needed surgical tools to accomplish vas-

cular reconstruction.

Soon a new policy of vascular reconstruction to restore or

maintain perfusion to injured extremities was begun under

the guidance of Hughes, Edward Janke, and S.F. Seeley.

1,4

This program and the clinical successes of Easy Medical Com-

pany represented the first deviation from the practice of liga-

tion started by Paré more than a century earlier. By using the

techniques of direct anastomosis, lateral repair, and inter-

position graft placement, the initial limb salvage rates were

encouraging.

7,8

Figure 1-1. Members of Easy Medical Company, a U.S. Marine Corps unit in the First Marine Division in Korea in 1952. Frank Spencer is standing

second from the left. (From Spencer FC. J Trauma 2006;60:906-909.)

5

CHAPTER 1 Historical Perspectives in Vascular Surgery: The Evolution of Modern Trends

Subsequently, a contingent of Army surgeons returned to

Korea armed with additional surgical techniques at the same

time that the medical evacuation helicopter was being fully

implemented. The combination of these events provided

the momentum for vascular repair to begin in earnest in the

mobile Army surgical hospitals (MASHs). Amputation rates

associated with extremity vascular injury declined dramati-

cally. In his landmark review of more than 300 major arterial

repairs performed during the Korean War, Hughes reported a

13% amputation rate.

4,9,10

Vietnam War

The experience of DeBakey during World War II and the

achievements of Hughes and others in Korea were advanced in

the Vietnam War. Foremost, the importance of rapid transport

of the wounded soldier to surgical care was realized. In one

report, 95% of wounded patients reached surgical attention by

helicopter within 2 hours of injury.

11

Recognizing the opportu-

nity, Norman Rich and Hughes initiated the Vietnam Vascular

Registry in 1966 to document and analyze vascular injuries.

12

In a review of more than 1000 arterial injuries treated during

the Vietnam War, Rich and Hughes reported a limb salvage

rate of 87%.

13

The Vietnam Vascular Registry also provided

vital information related to venous injuries, missile emboli,

concomitant bony and vascular injuries, type of bypass mate-

rial (prosthetic versus autogenous), and utility of continuous

wave Doppler to assess perfusion of the injured extremity.

14-16

Global War on Terror (2001 to Present)

Contemporary experience with wartime vascular injury has

confirmed and extended past military contributions. Mod-

ern successes are based on the premise established by Larrey

200 years ago of rapid transport of the injured to surgical exper-

tise. Operations in Iraq and Afghanistan represent the first in

which defined forward surgical capability has been used for a

prolonged period during different phases of warfare. Deploy-

ment of level 2 surgical teams (general and orthopedic surgeons

with anesthesia and corpsman support) near the site of injury,

in combination with rapid casualty evacuation, means that most

wartime injuries are now treated within 1 hour of wounding.

17

The broad use of commercially engineered tourniquets and

body armor has prevented immediate death in many injured

soldiers.

17

But, the result has been a three- to fivefold increase

in the rate of vascular injury seen on the modern battlefield.

Contemporary success with vascular injury management is also

based on the near-exclusive use of autologous vein for conduit,

as well as an aggressive approach to repair of extremity venous

injuries. Interestingly, the importance of the continuous wave

Doppler first advocated by Lavenson, Rich, and Strandness to

assess perfusion of injured extremities in wartime has been

further validated in current military endeavors.

18

Novel or groundbreaking perspectives have also stemmed

from current wartime experience.

19,20

These innovations

include the effectiveness of temporary vascular shunts to

restore or maintain perfusion until vascular reconstruction

can occur. While this technique was first described in the 1950s

during the French-Algerian War and again by the Israelis in the

early 1970s, the use of temporary vascular shunts in Iraq has

been more extensive.

4,21

Current observations have allowed

clinical study and discernment of vascular injury patterns

most amenable to this damage control adjunct versus those

best treated with the time-honored technique of ligation.

19

Another first in warfare management of vascular injuries

has been endovascular capabilities introduced to diagnose and

treat select injury patterns.

22

While catheter-based procedures

are not common in wartime, this capability has been shown

to extend the diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium

of the surgeon during wartime. In some cases, endovascular

therapy has provided the preferred or standard therapy (e.g.,

coil embolization of pelvic fracture or solid organ injury and

placement of covered stents).

Another major advance has been negative pressure wound

therapy, or VAC (KCI, San Antonio, Texas), which has revo-

lutionized the management of complex soft-tissue wounds

associated with vascular injury.

23,24

This closed wound man-

agement strategy was not available during previous military

conflicts, and its rapid acceptance and common use has made

it a standard now used in some phase of nearly all battle-

related soft-tissue wounds.

Finally, contemporary wartime experience has prompted a

historic reevaluation of the resuscitation strategy applied to the

most severely injured. Damage control resuscitation is based

on the use of blood products with a high ratio of fresh fro-

zen plasma to packed red blood cells, minimal crystalloid, and

selective use of recombinant factor VII.

25

This relatively new

strategy has increased survival in injured patients who arrive

with markers of severe physiological compromise (e.g., hypo-

tension, hypothermia, anemia, acidosis, or coagulopathy).

BEGINNINGS OF AORTIC SURGERY

The first operations on the aorta took place in the early 1800s

and were for aneurysmal disease, invariably due to syphilis,

in young to middle-aged men. In 1817, Sir Astley Cooper,

a student of John Hunter, ligated the aortic bifurcation in

a 38-year-old man who had suffered a ruptured iliac artery

aneurysm.

26

The patient died soon after the operation. Keen,

Tillaux, Morris, and Halstead reported similar attempts to

ligate aortic and iliac artery aneurysms without patient sur-

vival in the 100 years following Cooper’s initial report.

1

In 1888, during the era of arterial ligation for aneurysmal

disease, Rudolph Matas revived the dormant but centuries-

old concept of endoaneurysmorrhaphy. Nearly 16 centuries

earlier, Antyllus had introduced the concept of opening and

evacuating the contents of the arterial aneurysm sac. Matas

successfully performed the technique on a brachial artery

aneurysm, after an initial attempt at proximal ligation had

failed, in a patient named Manuel Harris, who had a traumatic

aneurysm following a shotgun injury to his arm.

27

Although in

this instance the technique was successful, Matas was reluctant

to apply this method broadly during the era when aneurysm

ligation was the prevailing dogma. The technique of open

endoaneurysmorrhaphy was not used for more than a decade

following Matas’s original description.

In 1923, while professor of surgery and the chief of the

Department of Surgery at Tulane University, Matas was the

first to ligate successfully the abdominal aorta for aneurysmal

disease with survival of his patient.

28

He reported this tech-

nique again in 1940.

29

Matas eventually improved and refined

the technique of open endoaneurysmorrhaphy, described

in three forms: obliterative, restorative, and reconstructive.

The reconstructive form allowed for maintenance of arterial

SECTION I Background

6

patency. In all, Matas operated on more than 600 abdominal

aortic aneurysms, with remarkably low morbidity and mor-

tality rates. In 1940, at the age of 80 years, he presented his

experience with the operative treatment of abdominal aortic

aneurysms to the American Surgical Association.

30

Through

his success and pioneering techniques, Matas demonstrated

the efficacy of a direct operative approach to the aorta and

began the era of aortic reconstruction.

Matas is widely held as the father of American vascular sur-

gery. In 1977, during the organization of the Southern Asso-

ciation for Vascular Surgery, a likeness of Matas was chosen

as the new society’s logo (Figure 1-2).

31

In one of his most

significant addresses, “The Soul of the Surgeon,” he estab-

lished and emphasized the qualities of a surgeon to which we

all should aspire.

32

PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL

RECONSTRUCTION

During this same era, vascular reconstruction of the periph-

eral arteries was developing rapidly. The first attempts to

place venous autografts into the peripheral circulation were

described by Alfred Exner in Austria and Alexis Carrel in

France at the beginning of the twentieth century.

1

Separately,

these two individuals pioneered the vascular anastomosis.

Exner used techniques with Erwin Payr’s magnesium tubes,

while Carrel used segments of vein. Carrel and Charles Guthrie

developed the model of the arterial anastomosis in dogs at the

Hull Physiological Laboratory in Chicago.

33

In 1912, Carrel

was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in

“recognition of his work on vascular suture and the transplan-

tation of blood vessels and organs.”

Guthrie, who was born in Missouri, returned to Washing-

ton University in St. Louis as professor. He eventually joined

the faculty at the University of Pittsburgh as the chairman

of physiology and pharmacology. A likeness of Guthrie was

designated as the logo for the Midwestern Vascular Surgical

Society during its first annual meeting at the Drake Hotel in

Chicago in 1977 (Figure 1-3).

34

The first use of a venous autograft in the human arterial cir-

culation was performed by the Spanish surgeon José Goyanes

in 1906, following resection of a syphilitic popliteal aneurysm.

One year later, a German surgeon, Erich Lexer, used a reversed

greater saphenous vein as an interposition graft in the axillary

position of the arm.

1

The modern technique of venous grafting fell out of favor

following these initial reports until revived by Jean Kunlin

with dramatic success in 1948 in Paris. One of Kunlin’s first

patients was initially under the care of his close associate René

Leriche. The patient had persistent ischemic gangrene follow-

ing sympathectomy and femoral arteriectomy. Kunlin per-

formed a greater saphenous vein bypass from the femoral to

the popliteal artery in his patient, employing end-to-side anas-

tomotic techniques at the proximal and distal aspects of the

bypass. The concept of end-to-side anastomosis was impor-

tant as it allowed for preservation of side branches. In 1951,

Kunlin reported his results of 17 such bypass operations.

35

In

1955, Robert Linton, from Massachusetts General Hospital,

popularized use of the reversed greater saphenous as a bypass

conduit in the leg, when he reported his experience.

36

Heparin was first discovered in 1916 by Jay Maclean and

reported in 1918.

37

However, heparin remained too toxic for

clinical use until Best and Scott reported the purification of

heparin in 1933.

38

Four years later, in 1937, Murray dem-

onstrated that heparin could prevent thrombosis in venous

bypass grafts.

39

Murray and Best noted that the use of this

novel anticoagulant was important not only during repair of

blood vessels but also in treatment of venous thrombosis.

39,40

The availability of heparin emboldened surgeons to attempt

vascular reconstructions that had been complicated previ-

ously by high rates of thrombosis.

AORTIC THROMBOENDARTERECTOMY

In the early 1900s, Severeanu, Jianu, and Delbet first described

thromboendarterectomy. These attempts were before the dis-

covery of heparin and generally resulted in failure due to early

thrombosis.

1

Subsequently, the technique was abandoned

until the mid-1940s, when John Cid Dos Santos performed

the first successful thromboendarterectomy of the aortoiliac

Figure 1-3. Charles Guthrie, as illustrated in the official logo of the

Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society. (From Pfeifer JR, et al.

34

)

Figure 1-2. Official seal of the Southern Association for Vascular Sur-

gery. (From Ochsner J. J Vasc Surg 2001;34:387-392.)

7

CHAPTER 1 Historical Perspectives in Vascular Surgery: The Evolution of Modern Trends

segment using an ophthalmic spatula and a gallstone scoop.

8

Edwin Wylie in San Francisco and others soon took up and

perfected the technique of aortic thromboendarterectomy in

the United States.

41,42

Wylie and colleagues developed and

extended endarterectomy techniques to the great vessels,

aorta, mesenteric arteries, and renal arteries. The technique of

thromboendarterectomy was also used briefly for the manage-

ment of some abdominal aortic aneurysms, as described by

Wylie, who reported the use of fascia lata to wrap an aneurys-

mal aorta following thromboendarterectomy and tailoring of

the vessel.

43

DEVELOPMENT OF AORTIC

PROSTHESES

Successful operations for aortic coarctation in the 1940s by

Clarence Crafoord in Sweden and Robert Gross in the United

States stimulated interest in arterial homografts that might

be used when primary aortic repair could not be accom-

plished.

44,45

In 1948, Gross and colleagues reported the use of

preserved arterial grafts in humans with cyanotic heart disease

and aortic coarctation.

46

Initial successes with arterial homografts in pediatric and

cardiac surgery led to their use in the operative treatment of

aortoiliac occlusive disease and aortic aneurysms. In 1950,

Jacques Oudot replaced a thrombosed aortic bifurcation with

an arterial homograft. One year later, another French vascular

surgeon, Charles Dubost (Figure 1-4), did the same following

resection of an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

47,48

Arterial homografts seemed initially to be an effective

substitute for the thoracic and abdominal aorta. At first,

fresh grafts were used; then, Tyrode solution, a preservative,

was used to preserve grafts for short periods. Development of

the techniques of freezing and lyophilization allowed for the

establishment of artery banks.

49,50

Despite early successes,

arterial homografts did not provide a durable bypass con-

duit for the aorta due to aneurysmal degeneration or fibrotic

occlusions. A satisfactory aortic substitute was still lacking.

The eventual development of synthetic grafts propelled

aortic surgery to its current maturity. As a surgical research

fellow at Columbia University under the mentorship of Arthur

Blakemore, Arthur Voorhees made a fortuitous observation

in 1947. Voorhees recognized that a silk suture inadvertently

placed in the ventricle of the dog became “coated in endocar-

dium” after a period in vivo. His observation caused him to

speculate that a “cloth tube acting as a lattice work of threads

might indeed serve as an arterial prosthesis.”

1

In 1948, during an assignment to Brooke Army Medical

Center in San Antonio, Texas, Voorhees fashioned synthetic

grafts from parachute material and placed them in the aor-

tic position of the dog. Although few of the initial prostheses

lasted for more than a week, Voorhees remained optimistic

and returned to Columbia in 1950 to resume his surgical

residency. Alfred Jaretzki joined Voorhees and Blakemore

in 1951, and their collaboration resulted in a report in 1952

of cloth prostheses in the animal aortic position.

1,51

Having

established the efficacy of such in the animal model, the group

reported the use of vinyon-N cloth tubes used to replace the

abdominal aorta in 17 patients with abdominal aortic aneu-

rysms in 1954.

1,52

Unfortunately, the early synthetic fabrics

available were subject to degenerative problems, as well as

failure to be incorporated.

DeBakey’s (Figure 1-5) introduction of knitted Dacron in

1957 allowed widespread application of the prosthetic graft

replacement technique for large- and medium-sized arteries,

and modern conventional aortic surgery began in earnest.

53

Modifications of the knitted Dacron graft were provided ini-

tially by Cooley and Sauvage and later by others; these modi-

fications improved the original knitted Dacron that DeBakey

provided.

54

THORACOABDOMINAL AORTIC

ANEURYSMS AND AORTIC

DISSECTIONS

Samuel Etheredge performed the first successful repair of a

thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm in 1954.

55

Etheredge used

a plastic tube or shunt, first proposed by Schaffer in 1951,

to maintain distal aortic perfusion as he moved the clamp

Figure 1-4. Charles Dubost. (From Friedman SG. J Vasc Surg

2001;33:895-898.)

Figure 1-5. Michael DeBakey, MD. (From McCollum CH. J Vasc Surg

2000;31:406-409.)

SECTION I Background

8

down the graft after each successive visceral anastomosis

had been completed. DeBakey and colleagues used modi-

fications of Etheredge’s technique and extended the use of

graft replacement and bypass to visceral arteries in patients

with thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. In 1956, DeBakey,

Creech, and Morris reported a series of complicated tho-

racoabdominal aneurysm repairs involving the renal and

mesenteric arteries.

56

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Wylie and Ronald Stoney

in San Francisco popularized the long, spiral thoracoabdomi-

nal incision for the approach of thoracoabdominal aortic

aneurysms.

33

In his discussion of Wylie and Stoney’s paper,

Etheredge made reference to the polyethylene bypass tube that

he had used as a shunt during his original aneurysm resec-

tion. Etheredge noted that he had “fashioned the tube over

his gas kitchen stove with a spoon for shaping.” Also during

the discussion, Etheredge showed pictures of the original tho-

racoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair, including a picture of

the patient 18 years after operation.

57

Extending the work of Matas and Carrel, DeBakey’s

younger partner, E. Stanley Crawford, provided the greatest

advancement in the operative management of thoracoabdom-

inal aortic aneurysms. Crawford introduced a direct approach

to the aneurysm, where the aorta was clamped above and

below the aneurysm and then opened longitudinally through-

out the aneurysm’s length.

58,59

A fabric graft was then sewn

into the lumen of the proximal and distal aorta into non-

aneurysmal artery. Inclusion of major groups of intercostal or

visceral vessels were then sewn into the wall of the fabric graft

using modifications of Carrel’s patch method of anastomosis,

sometimes referred to as a “Crawford window.”

58,59

The ability to handle aortic dissections operatively was

first reported by DeBakey with primary resection, as well as

fenestration. DeBakey himself underwent operation for aortic

dissection in his 90s; he died several years later at the age of 99

(2008). In recent years, aortic stent grafts have become impor-

tant in managing both thoracic aortic dissections (type B) and

descending and some arch aneurysms.

MESENTERIC OCCLUSIVE DISEASE

In 1936, Dunphy first recognized the clinical and anatomi-

cal entity known now as chronic mesenteric ischemia. He

reviewed autopsy results of patients dying of gut infarction

from mesenteric artery occlusions and documented that

most patients had the prodrome of abdominal pain and

weight loss associated with this syndrome.

60

Robert Shaw and

E.P. Maynard III, from Massachusetts General Hospital, first

reported thromboendarterectomy of the paravisceral aorta

and superior mesenteric artery for treatment of chronic intes-

tinal ischemia in 1958.

61

Following this report, Morris et al.

described the use of a retrograde aortomesenteric bypass

using knitted Dacron in the treatment of chronic mesenteric

ischemia.

62

Although this technique avoided exposure of the

midaorta, it was associated with tortuosity and kinking of the

retrograde grafts.

The early experience with retrograde grafts and the prob-

lem with tortuosity led Wylie and Stoney to develop other

techniques to establish visceral flow.

57,63

Wylie’s technique

evolved from experience doing renal endarterectomy and was

facilitated by the thoracoretroperitoneal approach that he had

championed for the exposure of thoracoabdominal aortic

aneurysms.

57,63

Transaortic endarterectomy was accomplished

through a trapdoor aortotomy and eversion endarterectomy

of the mesenteric vessels. This technique is now applied trans-

abdominally after medial visceral rotation to avoid the mor-

bidity of the thoracoabdominal incision.

CAROTID ARTERIAL RECONSTRUCTION

The prevailing thought at the turn of the twentieth century was

that the major cause of stroke was intracranial vascular disease.

A neurologist, Ramsay Hunt, was one of the first to assert that

the extracranial carotid circulation was a potential source of

cerebral infarcts. In an address to the American Neurological

Association in 1913, he recommended the routine examination

of the carotid arteries in patients with cerebral symptoms.

64

Egas Moniz described the first cerebral arteriography in

1927, originally as a technique to diagnose cerebral tumors.

1

In 1950, a neurologist from Massachusetts General Hospital,

Miller Fisher reported the results of postmortem examina-

tions of the brains of patients who had died from cerebral vas-

cular occlusive disease. In his observations, Fisher found that

a minority of strokes were caused by primary hemorrhagic

disease, and he concluded that the majority of strokes were

caused by embolic disease.

65,66

Three years after Fisher proclaimed that “it is conceivable

that some day vascular surgery will find a way to bypass the

occluded portion of the artery,”

1

DeBakey performed the first

carotid endarterectomy in the United States. He performed

a thromboendarterectomy on the patient, a 53-year-old man

with a symptomatic carotid stenosis; closed the artery primar-

ily; and confirmed patency with an intraoperative arterio-

gram.

67

Nine months later, Felix Eastcott, George Pickering,

and Charles Rob (Figure 1-6) successfully treated a patient

with a symptomatic carotid stenosis by means of a carotid

bulb resection and primary end-to-end anastomosis of the

internal and common carotid arteries.

68

Figure 1-6. Charles Rob and Felix Eastcott, 1960. (From Rosenthal D.

J Vasc Surg 2002;36:430-436.)

9

CHAPTER 1 Historical Perspectives in Vascular Surgery: The Evolution of Modern Trends

In 1961, Yates and Hutchinson further emphasized the

importance of extracranial carotid occlusive disease as a cause

of stroke.

69

Jack Whisnant, from the Mayo Clinic, identi-

fied the risk of stroke in the presence of transient ischemic

attacks and provided additional basis for operation on

symptomatic disease of the carotid arteries and great ves-

sels, which was becoming widely accepted.

70

Endarterectomy

or “disobliteration” of not only symptomatic carotid lesions

but also lesions of the subclavian and innominate arteries was

advanced by investigators such as Jesse Thompson in Dallas,

Wylie in San Francisco, and Inahara in Portland, Oregon.

These investigators, as well as others, refined techniques,

determined the range of uses, and clarified indications and

contraindications. The origins of prophylactic carotid endar-

terectomy for asymptomatic disease, a topic of debate today,

can be traced to Jesse Thompson and colleagues in Dallas in

the mid-1970s.

71

EVOLUTION OF ENDOVASCULAR

PROCEDURES

A Swedish radiologist, Sven-Ivar Seldinger (1921 to 1998),

described a minimally invasive access technique to the artery

in 1953.

72

Seldinger’s technique used a catheter passed over

a wire that in turn was introduced through the primary arte-

rial puncture site. The wire was advanced to the desired site,

and then the appropriate catheter was advanced over the wire.

Previous to Seldinger’s technique, arteriography was limited

and performed using a single needle at the puncture site in the

artery for the injection of contrast material.

One decade after Seldinger’s technique had been described,

Thomas Fogarty (Figure 1-7) and colleagues reported the use

of the thromboembolectomy catheter. That report in 1963,

while Fogarty was a surgical resident, detailed the use of a

balloon-tipped catheter to extract thrombus, embolus, or

both from a vessel lumen without having to open the vessel.

73

A year later, Charles Theodore Dotter (Figure 1-8) reported the

use of a rigid Teflon dilator passed through a large radiopaque

catheter sheath to perform the first transluminal treatment of

diseased arteries.

74

Five years after his original report, Dotter elaborated on a

technique for percutaneous transluminal placement of tubes

Figure 1-7. Thomas Fogarty. (Courtesy Thomas Fogarty.)

Figure 1-8. Charles Theodore Dotter. (Courtesy The Dotter Interven-

tional Institute, Portland, Ore.)

Figure 1-9. Andreas Gruntzig. (Courtesy Emory University School of

Medicine, Atlanta.)

SECTION I Background

10

within arteries to relieve obstructed arteries and restore blood

flow.

75

Together, the work of Fogarty and Dotter in the early

to mid-1960s heralded an evolution from diagnostic to diag-

nostic and therapeutic endovascular procedures.

Silastic balloons were later introduced by a Swiss radiolo-

gist, Andreas Gruntzig (Figure 1-9), who extended the work

of Fogarty and Dotter and in 1974 reported that percutane-

ous transluminal angioplasty with a silastic balloon could be

performed in different vascular beds, including coronary,

renal, iliac, and femoral.

76

Metallic stents in various designs

followed percutaneous balloon angioplasty, beginning with

the stent developed by Julio Palmaz (Figure 1-10) in 1985.

77

Arguably the greatest advance in transluminal endovascu-

lar interventions came when Juan Parodi (Figure 1-11) per-

formed the first endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm

repair.

78

His repair merged the old and the new by attach-

ing a woven Dacron graft to a Palmaz stent and delivering it

through a large-bore sheath placed via surgical exposure of

the femoral artery.

CONCLUSION

The management of patients with peripheral vascular dis-

ease has evolved such that effective treatments often can

be performed not only with minimal morbidity but also

with short—and, in many cases, no—hospital stay. We

have evolved such that the effectiveness of a procedure or

treatment is critically assessed in clinical research studies

in thousands of patients and measured by single-digit per-

centages. The pathophysiology and genetic basis of vascu-

lar disease are now understood so well in some cases that

disease processes are managed effectively with nonoperative

means. The rapidity with which the treatment of peripheral

vascular disease has evolved over the past century is

remarkable. We can only imagine how the practice of vas-

cular surgery will look during the next 50 years if such great

progress continues.

References

1. Friedman SG. A history of vascular surgery. New York: Futura; 1989.

2. Wangensteen WO, Wangensteen SD, Klinger CF. Wound management

of Ambrose Paré and Dominique Larrey, great French military surgeons

of the 16th and 19th centuries. Bull Hist Med 1972;46:207.

3. Makins GH. On gunshot injuries to the blood vessels. Bristol, UK: John

Wright & Sons; 1919.

4. Rich NM, Rhee P. An historical tour of vascular injury management:

from its inception to the new millennium. Surg Clin North Am 2001;81:

1199-1215.

5. DeBakey ME, Simeone FA. Battle injuries of arteries in World War II:

an analysis of 2471 cases. Ann Surg 1946;123:534-579.

6. Spencer FC. Historical vignette: the introduction of arterial repair into

the US Marine Corps, US Naval Hospital, in July-August 1952. J Trauma

2006;60:906-909.

7. Jahnke EJ, Seeley SF. Acute vascular injuries in the Korean War: an analy-

sis of 77 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 1953;138:158.

8. Hughes CW. The primary repair of wounds of major arteries. Ann Surg

1955;141:297.

9. Hughes CW. Arterial repair during the Korean War. Ann Surg

1958;147:155.

10. Jahnke EJ. Late structural and functional results of arterial injuries

primarily repaired. Surgery 1958;43:175.

11. Rich NM. Vietnam missile wound evacuation in 750 patients. Mil Med

1968;133:9.

12. Rich NM, Hughes CW. Vietnam vascular registry: a preliminary report.

Surgery 1969;65:218.

13. Rich NM, Baugh JH, Hughes CW. Acute arterial injuries in Vietnam:

1000 cases. J Trauma 1970;10:359-369.

14. Rich NM, Hughes CW, Baugh JH. Management of venous injuries. Ann

Surg 1970;171:724-730.

15. Rich NM. Vascular trauma. Surg Clin North Am 1973;53:1367-1392.

16. Rich NM, Collins Jr GJ, Anderson CA, et al. Missile emboli. J Trauma

1978;18:236-239.

Figure 1-11. Juan Parodi. (Courtesy Washington University, St. Louis.)

Figure 1-10. Julio Palmaz. (Courtesy Julio Palmaz.)

11

CHAPTER 1 Historical Perspectives in Vascular Surgery: The Evolution of Modern Trends

17. Rasmussen TE, Clouse WD, Jenkins DH, et al. Echelons of care and the

management of wartime vascular injury: a report from the 332nd EMDG/

Air Force Theater Hospital Balad Air Base Iraq. Persp Vasc Surg Endovasc

Ther 2006;10:1-9.

18. Lavenson Jr GS, Rich NM, Strandness Jr DE. Ultrasonic flow detector

value in combat vascular injuries. Arch Surg 1971;103:644-647.

19. Rasmussen TE, Clouse WD, Jenkins DH, et al. The use of temporary vas-

cular shunts as a damage control adjunct in the management of wartime

vascular injury. J Trauma 2006;61(1):8-12.

20. Chambers LW, Rhee P, Baker BC, et al. Initial experience of US Marine

Corps forward resuscitative surgical system during Operation Iraqi Free-

dom. Arch Surg 2005;140:26-32.

21. Eger M, Golcman L, Goldstein A, et al. The use of a temporary shunt

in the management of arterial vascular injuries. Surg Gyn Obst 1971;32:

67-70.

22. Rasmussen TE, Clouse WD, Peck MA, et al. Development and implementa-

tion of endovascular capabilities in wartime. J Trauma 2008;64:1169-1176.

23. Leininger BE, Rasmussen TE, Smith DL, et al. Experience with wound

VAC and delayed primary closure of contaminated soft tissue injuries in

Iraq. J Trauma 2006;61:1207-1211.

24. Peck MA, Clouse WD, Cox MW, et al. The complete management of

extremity vascular injury in a local population: a wartime report from the

332nd Expeditionary Medical Group/Air Force Theater Hospital, Balad

Air Base, Iraq. J Vasc Surg 2007;45:1197-1204.

25. Fox CJ, Gillespie DL, Cox ED, et al. The effectiveness of a damage control

resuscitation strategy for vascular injury in a combat support hospital:

results of a case control study. J Trauma 2008;64(Suppl 2):S99-S106.

26. Brock RC. The life and work of Sir Astley Cooper. Ann R Coll Surg Engl

1969;44:1-2.

27. Matas R. Traumatic aneurism of the left brachial artery. Med News

1888;53:462.

28. Matas R. Ligation of the abdominal aorta: report of the ultimate result,

one year, five months and nine days after ligation of the abdominal aorta

for aneurysm of the bifurcation. Ann Surg 1925;81:457.

29. Matas R. Aneurysm of the abdominal aorta at its bifurcation into the

common iliac arteries. Ann Surg 1940;112:909.

30. Matas R. Personal experiences in vascular surgery: a statistical synopsis.

Ann Surg 1940;112:802.

31. Ernst CB. The Southern Association for Vascular Surgery: the beginning.

J Vasc Surg 2001;34:381-383.

32. Matas R. The soul of the surgeon. Tr Miss M Assoc 1915;48:149.

33. Carrel A, Guthrie CC. Results of biterminal transplantation of veins.

Am J Med Sci 1906;132:415.

34. Pfeifer JR, Stanley JC. The Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society: the

formative years, 1976 to 1981. J Vasc Surg 2002;35:837-840.

35. Kunlin J. Le traitement de l’ischemie arteritique par la greffe veineuse

longeu. Rev Chir 1951;70:206.

36. Linton RR. Some practical considerations in surgery of blood vessels.

Surgery 1955;38:817.

37. Howell WH. Two new factors in blood coagulation: heparin and proan-

tithrombin. Am J Physiol 1918;47:328-341.

38. Best CH, Scott C. The purification of heparin. J Biol Chem 1933;102:425.

39. Murray DWG, Best CH. The use of heparin in thrombosis. Ann Surg

1938;108:163.

40. Murray DWG. Heparin in surgical treatment of blood vessels. Arch Surg

1940;40:307.

41. Wylie EJ. Thromboendarterectomy for atherosclerotic thrombosis of

major arteries. Surgery 1952;32:275.

42. Freeman NE, Gilfillan RS. Regional heparinization after thromboendar-

terectomy in the treatment of obliterative arterial disease: preliminary

report based on 12 cases. Surgery 1952;31:115.

43. Wylie Jr EJ, Kerr E, Davies O. Experimental and clinical experience

with the use of fascia lata applied as a graft about major arteries after

thromboendarterectomy and aneurysmorrhaphy. Surg Gynecol Obstet

1951;93:257.

44. Crafoord C, Nylin G. Congenital coarctation of the aorta and its surgical

treatment. J Thorac Surg 1945;14:347-361.

45. Gross RE. Treatment of certain aortic coarctations by homologous grafts:

a report of nineteen cases. Ann Surg 1951;134:753.

46. Gross RE, Hurwitt ES, Bill Jr AH, et al. Preliminary observations on the

use of human arterial grafts in the treatment of certain cardiovascular

defects. N Engl J Med 1948;239:578-579.

47. Oudot J, Beaconsfield P. Thrombosis of the aortic bifurcation treated

by resection and homograft replacement: report of five cases. Arch Surg

1953;66:365-370.

48. Dubost C, Allary M, Oeconomos N. Resection of an aneurysm of

the abdominal aorta: re-establishment of the continuity by a pre-

served human arterial graft, with results after five months. Arch Surg

1952;64:405-408.

49. Deterling Jr RA, Coleman CC, Parshley MS. Experimental studies on the

frozen homologous aortic graft. Surgery 1951;29:419.

50. Marangoni AG, Cecchini LP. Homotransplantation of arterial segments

by the freeze-drying method. Ann Surg 1951;134:977.

51. Voorhees Jr AB, Jaretzki A III, Blakemore AH. Use of tubes constructed

from vinyon-N cloth bridging arterial defects. Ann Surg 1952;135:332.

52. Blakemore A, Voorhees Jr AB. The use of tubes constructed from vinyon-

N cloth in bridging arterial defects: experimental and clinical. Ann Surg

1954;140:324-334.

53. DeBakey ME, Cooley DA, Crawford ES, et al. Clinical application of a

new flexible knitted Dacron arterial substitute. Arch Surg 1958;77:713.

54. Sauvage G, Berger KE, Wood SJ, et al. An external velour surface for

porous arterial prosthesis. Surgery 1971;70:940-953.

55. Etheredge SN, Yee JY, Smith JV, et al. Successful resection of a large aneu-

rysm of the upper abdominal aorta and replacement with homograft.

Surgery 1955;38:1071.

56. DeBakey ME, Creech O, Morris GC. Aneurysm of the thoracoabdomi-

nal aorta involving the celiac, mesenteric and renal arteries: report of

four cases treated by resection and homograft replacement. Ann Surg

1956;144:549-573.

57. Stoney RJ, Wylie EJ. Surgical management of arterial lesions of the thora-

coabdominal aorta. Am J Surg 1973;126:157-164.

58. DeBakey ME, Crawford ES, Garrett HE, et al. Surgical considerations in

the treatment of aneurysms of the thoracoabdominal aorta. Ann Surg

1965;162:350-362.

59. Crawford ES. Thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysms involving renal,

superior mesenteric and celiac arteries. Ann Surg 1974;179:763-772.

60. Dunphy JE. Abdominal pains of vascular origins. Am J Med Sci

1936;192:109.

61. Shaw RS, Maynard EP. Acute and chronic thrombosis of the mesenteric

arteries associated with malabsorption. N Engl J Med 1958;258:874.

62. Morris GC, Crawford ES, Cooley DA, et al. Revascularization of the celiac

and superior mesenteric arteries. Arch Surg 1962;84:95-107.

63. Stoney RJ, Ehrenfeld WK, Wylie EJ. Revascularization methods in chronic

visceral ischemia. Ann Surg 1977;186:468-476.

64. Hunt JR. The role of the carotid arteries in the causation of vascular

lesions of the brain with remarks on certain special features of the symp-

tomatology. Am J Med Sci 1914;147:704-713.

65. Fisher M. Occlusion of the internal carotid artery. Arch Neurol Psychiat

1951;65:346-377.

66. Fisher M, Adams RD. Observation on brain embolism with special

reference to the mechanism of hemorrhagic infarction. J Neuropath Exp

Neurol 1951;10:92.

67. DeBakey ME. Successful carotid endarterectomy for cerebral vascular

insufficiency: nineteen year follow up. JAMA 1975;233:1083-1085.

68. Eastcott HHG, Pickering GW, Rob C. Reconstruction of internal carotid

artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet 1954;

2:994-996.

69. Yates PO, Hutchinson EC. Cerebral infarction: the role of stenosis of the

extracranial arteries. Med Res Council Spec Report (London) 1961;300:1.

70. Whisnant JP, Matsumoto N, Elveback LR. Transient cerebral ischemic

attacks in a community: Rochester, Minnesota, 1955 through 1969. Mayo

Clin Proc 1973;48:194-198.

71. Thompson JE, Patman RD, Talkington CM. Asymptomatic carotid bruit.

Ann Surg 1978;188:308-316.

72. Seldinger S. Catheter placement of the needle in percutaneous arteriog-

raphy: a new technique. Acta Radiol 1953;39:368.

73. Fogarty T, Cranley J, Krause R, et al. A method for extraction of arterial

emboli and thrombi. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1963;116:241.

74. Dotter CT, Judkins MP. Transluminal treatment of arteriosclerotic

obstruction. Circulation 1964;30:654-670.

75. Dotter CT. Transluminally placed coilspring endarterial tube grafts: long-

term patency in canine popliteal artery. Invest Radiol 1969;4:329-332.

76. Gruntzig A, Hopff H. Perkutane rekanalisation chronischer arterieller

verschlusse mit einem neuen dilatationskatheter: modifikation der

dotter-technik. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1974;99:2502-2510.

77. Palmaz J, Sibbitt R, Reuter S, et al. Expandable intraluminal graft: a pre-

liminary study. Radiology 1985;156:72-77.

78. Parodi JC, Palmaz JC, Barone HD. Transfemoral intraluminal graft

implantation for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg 1991;5:

491-499.

12

2

Vascular Biology

Virginia M. Miller, PhD

Key Points

• Endovascular and vascular surgeons are

largely concerned with correction of

degenerative vascular disease, explained

by the abnormal biology (or pathology) of

blood vessels.

• Biological responses of blood vessels to

vascular and endovascular procedures limit the

long-term success of mechanical intervention.

• Understanding vascular biology may lead

to the development of new medical and

interventional techniques.

• The balance in production and release

of endothelium-derived relaxing and

contracting factors affects how injured and

grafted blood vessels heal.

• Production and release of endothelium-

derived factors are influenced by

hemodynamic changes, sex steroid

hormones, infection, and aging.

• Growth factors and enzymes released

from blood elements interacting with the

blood vessel wall promote development of

intimal hyperplasia.

• Monogenic vascular disorders are

uncommon, but they provide valuable

insight into mechanisms of vascular

disease.

• Growth factors, together with extracellular

matrix cues, regulate the growth of new

blood vessels. Growth factors can be

used as adjuncts for revascularization and

recovery of tissue loss.

• Sex, hormonal status, and immunological

competence are confounding factors that

modulate vascular healing.

Many contemporary challenges faced

by vascular and endovascular surgeons

have their basis in vascular pathology, or

abnormal vascular biology. The success

of endovascular aneurysm repair depends

partly on the absence of endoleak through

lumbar and other vessels and arresting the

process of aortic dilatation at the aneu-

rysm neck. The success of peripheral bypass surgery depends

on the limitation of anastomotic hyperplasia and controlling

the progression of atherosclerosis in inflow and outflow ves-

sels. Intimal hyperplasia with recurrent stenosis is a common

consequence of femoral angioplasty. In other cases, tissue loss