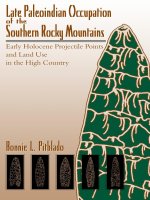

university press of colorado late paleoindian occupation of the southern rocky mountains early holocene projectile points and land use in the high country mar 2003

Bạn đang xem bản rút gọn của tài liệu. Xem và tải ngay bản đầy đủ của tài liệu tại đây (1.73 MB, 314 trang )

Late Paleoindian Occupation

of the

Southern Rocky Mountains

Late Paleoindian Occupation

of the

Southern Rocky Mountains

Early Holocene Projectile Points

and Land Use

in the High Country

Early Holocene Projectile Points

and Land Use

in the High Country

Bonnie L. Pitblado

Bonnie L. Pitblado

Late Paleoindian Occupation

of the

Southern Rocky Mountains

Bonnie L. Pitblado

Late Paleoindian Occupation

Southern Rocky Mountains

University Press of Colorado

of the

Early Holocene Projectile Points

and Land Use

in the High Country

© 2003 by the University Press of Colorado

Published by the University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

The University Press of Colorado

is a proud member of the

Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams

State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State

College of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of

Southern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National

Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-

1992

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pitblado, Bonnie L., 1968–

Late Paleoindian occupation of the southern Rocky Mountains : early Holocene projectile points

and land use in the high country / Bonnie L. Pitblado.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87081-728-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Paleo-Indians—Colorado. 2. Paleo-Indians—Utah. 3. Paleo-Indians—Rocky Mountains. 4. Land

settlement patterns, Prehistoric—Rocky Mountains. 5. Projectile points—Rocky Mountains. 6.

Colorado—Antiquities. 7. Utah—Antiquities. I. Title.

E78.C6 P58 2003

978.8—dc21

2003000199

Designed and Typeset by Laura Furney

12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my husband, Joe Dulin,

without whom nothing would be worthwhile;

and to Dr. Colin Pitblado,

a wonderful and inspirational dad and human being,

who I miss terribly.

Contents

List of Illustrations ix

Preface xv

Acknowledgments xvii

1 Introduction 1

2 Environment: Modern and Early Holocene 29

3 Hunter-Gatherer Land Use, Lithic Technology, and Late

Paleoindian Occupation of the Project Area 45

4 Projectile Point Analysis Procedure 65

5 Late Paleoindian Projectile Point Typology in the Western

United States 79

6 Late Paleoindian Projectile Points: Typological Variability 125

7 Late Paleoindian Projectile Points: Raw Material Variability 145

8 Late Paleoindian Projectile Points: Qualitative Technological

Variability 175

9 Late Paleoindian Projectile Points: Quantitative Technological

Variability 201

10 Late Paleoindian Projectile Points: Condition and Reworking 217

11 Discussion and Conclusions 231

Appendix A: Site Coding Guide 249

Appendix B: Projectile Point Coding Guide 255

References 263

Index 285

FIGURES

1.1 Colorado-Utah project area, showing location of Rocky

Mountains, Great Plains, Colorado Plateau, and Great Basin 3

1.2 Locations of late Paleoindian sites in the Rocky Mountains

mentioned in text 5

1.3 Relationship among environment, hunter-gatherer land use,

and technology 24

1.4 Hypothetical example of the relationship among environment,

late Paleoindian land use, and projectile point technology 25

2.1 Rocky Mountain environmental zones 33

4.1 Map showing locations of projectile points in Colorado-

Utah project area 67

4.2 Variants of longitudinal and transverse cross-section forms 73

4.3 Flaking intensity measurement procedure 73

4.4 Projectile point measurement procedure 75

5.1 Scottsbluff projectile points from the Colorado-Utah project

area 82

5.2 Locations of Scottsbluff sites 83

5.3 Eden/Firstview projectile points from the Colorado-Utah

project area 84

5.4 Locations of Eden/Firstview sites 85

5.5 Alberta projectile points from the Colorado-Utah project area 88

5.6 Locations of Alberta sites 88

5.7 Hell Gap/Haskett I projectile points from the Colorado-Utah

project area 90

5.8 Locations of Hell Gap/Haskett I sites 91

5.9 Great Basin Stemmed projectile points from the Colorado-

Utah project area 92

5.10 Locations of Great Basin Stemmed sites 93

Illustrations

ILLUSTRATIONSx

5.11 Pryor Stemmed projectile points from the Colorado-Utah

project area 98

5.12 Locations of Pryor Stemmed sites 98

5.13 Lovell Constricted projectile points from the Colorado-

Utah project area 101

5.14 Locations of Lovell Constricted sites 101

5.15 Concave Base Stemmed projectile points from the

Colorado-Utah project area 103

5.16 Locations of Concave Base Stemmed sites 103

5.17 Goshen/Plainview projectile points from the Colorado-

Utah project area 106

5.18 Locations of Goshen/Plainview sites 106

5.19 Agate Basin/Haskett Type II projectile points from the

Colorado-Utah project area 108

5.20 Locations of Agate Basin/Haskett Type II sites 109

5.21 Jimmy Allen/Frederick projectile points from the Colorado-

Utah project area 111

5.22 Locations of Jimmy Allen/Frederick sites 111

5.23 Angostura projectile points from the Colorado-Utah project

area 113

5.24 Locations of Angostura sites 114

5.25 Deception Creek projectile points from the Colorado-Utah

project area 118

5.26 Location of Deep Hearth site (Deception Creek) 118

5.27 Histograms of radiocarbon dates for best-dated projectile

point types 121

5.28 Plot of number of radiocarbon-dated occurrences against

date ranges, all projectile point types 123

6.1 Distribution of eight most common point types in regions of

the project area 130

6.2 Regional distribution of eight most common projectile

point types in Colorado-Utah 133

7.1 Lithic raw material sources identified in the Colorado-Utah

projectile point sample 146

7.2 Direction to raw material source by region 153

7.3 Distribution of distance classes for eight most common

projectile point types in the Colorado-Utah project area 163

8.1 Projectile point basal grinding by region 178

8.2 Projectile point blank form by region 180

ILLUSTRATIONS xi

TABLES

1.1 Extent of use of the Rockies and typology distribution

correlates 16

1.2 Extent of use and expected raw material selection in the

Southern Rockies 18

1.3 Extent of use of the Southern Rockies and expected

technological correlates 20

1.4 Extent of use of the Rockies and corresponding expectations:

projectile point typology, raw material use, and technology. 23

3.1 Accessibility of primary production and secondary biomass 47

3.2 Structure of faunal resources 48

3.3 Projectile point technology correlates of foraging and

collecting land use strategies 51

3.4 Accessibility of secondary biomass, fauna size/dispersion,

and inferred dominant late Paleoindian land use strategies

for project-area environments 53

3.5 Inferred relationships between dominant late Paleoindian

land use strategy and projectile point technology for project-

area environments 54

5.1 Radiocarbon dates associated with Scottsbluff projectile

points 82

5.2 Radiocarbon dates associated with Eden/Firstview projectile

points 86

5.3 Radiocarbon dates associated with Alberta projectile points 87

5.4 Radiocarbon dates associated with Hell Gap/Haskett Type I

projectile points 90

5.5 Radiocarbon dates associated with Great Basin Stemmed

projectile points 94–96

5.6 Radiocarbon dates associated with Pryor Stemmed projectile

points 97

5.7 Radiocarbon dates associated with Lovell Constricted

projectile points 99

5.8 Radiocarbon dates associated with Goshen/Plainview

projectile points 104–105

5.9 Radiocarbon dates associated with Agate Basin/Haskett

Type II projectile points 108

5.10 Radiocarbon dates associated with Jimmy Allen/Frederick

projectile points 110

5.11 Radiocarbon dates associated with Angostura projectile points 115–116

ILLUSTRATIONSxii

5.12 Median radiocarbon dates and date ranges for projectile

point types 120

6.1 Distribution of projectile point types by physiographic region 127

6.2 Distribution of eight most common projectile point types

by region 129

6.3 Distribution of eight most common projectile point types by

environmental zone 134

6.4 Distribution of eight most common projectile point types in the

Great Basin mountains and Rockies by environmental zone 136

6.5 Elevation statistics for projectile point types 138

6.6 Mean and median elevations for common point types,

Rockies versus non–Rocky Mountain contexts 139

7.1 Lithic raw material sources in the Colorado-Utah projectile

point assemblage 147

7.2 Distribution of raw material types by region 148

7.3 Distribution of raw material types by environment 148

7.4 Percentage quartzite and chert, projectile point versus non–

projectile point tool assemblages at four sites 150

7.5 Specific raw material types in the Colorado-Utah projectile

point assemblage 151

7.6 Distance from projectile point provenience to raw material

source by region 154

7.7 Distance from projectile point sites to nearest source of raw

material by region 155

7.8 Distance from projectile point sites to raw material source

by environmental zone 156

7.9 Distance from projectile points to source of material by

environmental zone 157

7.10 Cross-tabulation of eight most common projectile point

types by raw material 158

7.11 Distance-to-source statistics for projectile point types

with n > 5 165

8.1 Heat treatment of chert projectile points by region 176

8.2 Basal grinding by region 177

8.3 Projectile point type by blank form 181

8.4 Presence/absence of patterned flaking by region 184

8.5 Patterning in flaking and raw material by region 185

8.6 Flaking pattern by region 188

8.7 Mean and median distance-to-source for flaking patterns

by region 191

ILLUSTRATIONS xiii

8.8 Mean flaking intensity indexes for raw materials by region 194

8.9 Flaking intensity statistics for local and exotic stone by

region 195

8.10 Summary of technological variables and land use by region 200

9.1 Basic statistics for eight quantitative observations (all

point types) 203–204

9.2 Statistical significance of regional/environmental

differences in quantified observations 204

9.3 DMax by point type 205

9.4 MW by point type 205

9.5 MT by point type 205

9.6 Wgt by point type 205

9.7 BW by point type 205

9.8 CD by point type 205

9.9 StemRat by point type 206

9.10 EGINDX by point type 206

10.1 Condition of projectile points by region 219

10.2 Presence/absence of reworking by region 223

10.3 Intensity of reworking by region 223

10.4 Nature of reworking by region 223

ILLUSTRATIONSxiv

ILLUSTRATIONS xv

Preface

FOR DECADES, ARCHAEOLOGISTS and others with a passion for prehistory have

been enthralled by Paleoindian sites on the Great Plains and in the Great

Basin of the western United States. The Rocky Mountains that geographi-

cally separate these regions, however, have been the subject of considerably

less attention, although a few hardy archaeologists like Wil Husted, Jim

Benedict, Liz Morris, and George Frison have long stressed their role in the

human story.

Despite the lack of archaeological focus, the Rocky Mountains are vi-

tally important to our understanding of the earliest human adaptations in the

western United States. Obvious questions to be answered include: When did

human occupation of the Rockies fluoresce? Did Paleoindian people oc-

cupy the Rockies year-round, seasonally, or only sporadically? If Paleoindians

did not spend all year in the mountains, where did they spend the rest of

their time—to the east or to the west? How, specifically, did people move

around the mountain landscape? Did Rocky Mountain Paleoindian settle-

ment strategies differ from those practiced in neighboring lowland regions

to the east and west?

The research reported in this book attempts to answer these questions,

focusing most particularly on characterizing the extent and nature of human

occupation of the Southern Rocky Mountains, circa 10,000–7,500 years ago.

ILLUSTRATIONSxvi PREFACE

This is accomplished through a regional comparison of 589 late Paleoindian

projectile points from the Rockies, Plains, Colorado Plateau, and Great Ba-

sin of Colorado and Utah. Projectile point comparisons encompass three

independent axes of variability: typology, raw material, and technology.

To evaluate the extent of human use of the Southern Rockies 10,000–

7,500 years ago, Rocky Mountain projectile points are assessed for their simi-

larity to or difference from specimens from adjacent lowlands of the Plains,

Colorado Plateau, and Great Basin. The greater the similarity of the moun-

tain points to counterparts from the eastern and western lowlands, the more

likely it is that seasonal or sporadic visitors from those lowlands deposited

them. The greater the difference of the mountain points from counterparts

to the east and west, the more likely it is that they were deposited by people

uniquely adapted to full-time mountain existence.

To evaluate the nature of late Paleoindian use of the Rockies, a chain of

inferences is built linking regional environments to inferred land use strate-

gies (“logistical” versus “residential”) and inferred land use strategies to likely

projectile point characteristics. Then, actual Southern Rockies projectile point

characteristics are evaluated against those predicted by Rocky Mountain

environmental parameters. A match supports the environmentally based land

use model; lack of a match requires hypotheses explaining the dissonance.

Although the foremost goal and accomplishment of the research reported

here is to illuminate late Paleoindian use of the Southern Rocky Mountains,

this comparative project also yields data that answer questions about early

human use of the other regions of the Colorado-Utah project area: the Plains,

Colorado Plateau, and Great Basin. Wherever possible, the book expands

inferences beyond the mountains themselves to the lowland regions that

surround them and form the broader context within which the mountains

must be understood.

The result of this endeavor is twofold. First, the research yields a refined

“big-picture” view of human adaptations in the American West generally

and the Southern Rocky Mountains specifically, circa 10,000–7,500 years

ago. Second, the research yields testable hypotheses about the timing of early

human use of the Rockies, the extent of late Paleoindian use of the Rockies,

and the nature of late Paleoindian settlement strategies in not only the South-

ern Rockies but adjacent regions of the Plains, Colorado Plateau, and Great

Basin as well.

ILLUSTRATIONS xvii

A PROJECT LIKE THIS ONE, which entails extensive travel and contact with doz-

ens of people, rapidly accumulates debts of gratitude. First, I thank Cherie

Freeman and Sam Richings-Germain for the many hours spent helping me.

The value of the time these two wonderful women shared far exceeds any

monetary grant I received. I also thank R. A. Varney for his help with photo-

graphing artifacts and with various other research-related tasks; Jason Porter

for drafting most of the figures for this book; and Beth Ann Camp for me-

ticulously proofreading and creating an index for this manuscript.

Next I thank the many dear friends who shared their lives with me while

I conducted my studies on the road. Jean Kindig let me use a cozy loft in her

alpine “chalet” and plied me with Echinacea when the Boulder winter got

me down. Becky Hutchins loaned me everything from a spare bed to her

gym pass. Pam and Quentin Baker and Ron Rood shared spare bedrooms

and always made me laugh after a hard day of analysis.

Jim and Audrey Benedict, Bob and Becky Brunswig, and Bud and Sue

Phillips are second families—always welcoming and supportive. Patty Walker

Buchanan is also a terrific pal who shared her home, archaeological exper-

tise, contacts, and illustrating talent at every turn.

I also express my gratitude to the individuals who donated their exper-

tise, time, and meticulously documented projectile point collections for study.

Acknowledgments

ILLUSTRATIONSxviii

Scott DesPlanques, Mike Dollard, Bill Fox, Wynn Isom, Dick Louden, Rich-

ard Louden, Tom McCourt, Tom Pomeroy, Dann Russell, Steven Salas, Mark

Stuart, Bill Tilley, and Mike Toft all ensured that we now know more about

Paleoindian occupation of both Colorado and Utah.

In conducting research at various repositories, I greatly appreciated the

help of Bob Akerly, Brooke Arkush, Jim Benedict, Kevin Black, Don Burge,

Bill Butler, Donna Daniels, Jim Dixon, Kathy Fowler, Barbara Frank, George

Frison, Ric Hauck, Becky Hutchins, Marian Jacklin, Kathy Kankainen, Marcel

Kornfeld, Carolyn Landes, Fred Lange, Mary Lou Larson, Loretta Martin,

Lucha Martinez, Duncan Metcalfe, Pam Miller, Liz Morris, Brian Naze, Ron

Rood, Evie Seelinger, Richard Stucky, Mary Sullivan, Duane Taylor, and Susan

Thomas.

I express my deep appreciation to my Ph.D. committee, who helped

guide the research reported in this book. I shall be continually inspired by

the unparalleled scientific standards set by my mentor, Vance Haynes. George

Frison, who has done more for Rocky Mountain Paleoindian than anyone,

provided invaluable input. Mary Stiner and Steve Kuhn have always given

me advice I can take to the bank. Although not officially a member of my

committee, I also thank Wil Husted, a pioneer in studies of prehistoric occu-

pation of the Rocky Mountains, for inspiring me with his work and for

hours of great E-mail conversations about mountain Paleoindians.

Financially, this research was made possible primarily thanks to the Na-

tional Science Foundation (SBR-9624373). I also acknowledge funding from

the American Alpine Club, Arizona-Nevada Academy of Sciences, Colorado

Mountain Club, Colorado State University Foundation, Explorers Club,

Graduate Women in Science/Sigma Delta Epsilon, Hyatt Corporation,

Marshall Foundation, and the University of Arizona Anthropology Depart-

ment, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, and Graduate College.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS xix

Late Paleoindian Occupation

of the

Southern Rocky Mountains

OVERVIEW

The research reported in this book focuses on late Paleoindian occupa-

tion of the Southern Rocky Mountains, circa 10,000 to 7,500 (uncalibrated

radiocarbon) years ago. The Southern Rockies are an important arena for

study, both because they are a vast and environmentally distinct region with

a potentially unique late Paleoindian prehistory and because they constitute

the geographic interface between physiographic regions with different late

Paleoindian records: the Plains to the east and the Colorado Plateau and

Great Basin to the west.

Paradoxically, given their likely archaeological significance, the Southern

Rockies have been the subject of little Paleoindian-oriented fieldwork, and

the region has received even less consideration as a player in synthetic mod-

els of late Paleoindian occupation of the American West. To be sure, a hand-

ful of researchers (e.g., Benedict 1998, 2000; Black 1991; Husted 1962; Jodry

and Stanford 1992; Jodry et al. 1989; Kornfeld and Frison 2000; Morris and

Metcalf 1993) have provided the underpinnings for viewing late Paleoindian

use of the Southern Rockies within a broad context, but basic issues remain

unresolved, hampering refinement of a bigger picture.

Chief among the corpus of unresolved issues are two that form the crux

of the research reported in this book: (1) the extent to which the Southern

Introduction

1

INTRODUCTION2

Rockies were occupied during the late Paleoindian period—full-time, sea-

sonally, sporadically, or some combination thereof—and (2) how, specifically,

late Paleoindian groups moved across the Southern Rocky Mountain land-

scape—through systems of residential mobility, logistical mobility, or both

(Binford 1980). The goal of the research is to resolve these two issues and in

so doing to expand current understanding of the range of late Paleoindian

adaptations in the western United States.

Because the research situates the Southern Rockies within a very broad

context, methodology is regional in scope and comparative in nature. The

regional emphasis is reflected in the selection of the states of Colorado and

Utah as a project area (Fig. 1.1). The area encompasses the Rocky Moun-

tains, as well as the surrounding physiographic regions that provide the broad

context within which occupation of the Rockies must be understood: the

Plains to the east and the Colorado Plateau and Great Basin to the west.

The comparative requirements of the research design are met through

the selection of late Paleoindian projectile points as the analytical medium.

Projectile points are the only late Paleoindian artifact type ubiquitously rep-

resented in the project area. These artifacts are also suited for making con-

trolled comparisons across space because they are time sensitive and allow

chronology to be held constant. Moreover, projectile points vary along a

number of axes that can be explored independently and brought to bear on

the issues the research strives to resolve.

To determine the extent of human occupation of the Southern Rockies,

10,000–7,500

B.P., late Paleoindian projectile points from the mountains are

compared to those from adjacent lowland regions according to typology, raw

material use, and technology. The underlying principle is that the more time

people spent in the Rockies, the more their weaponry would have taken on

unique characteristics. By evaluating the extent to which projectile points

from the Rockies differ from or resemble those from adjacent regions, the

degree of late Paleoindian commitment to the mountain environment can

be gauged.

The process for evaluating how late Paleoindian groups utilized the Rocky

Mountain landscape rests upon two well-established anthropological pre-

mises: (1) environment plays an important role in structuring the way hunter-

gatherers use the landscape (e.g., Binford 1980; Kelly 1983); and (2) the way

hunter-gatherers use the landscape structures how they make and use chipped

stone tools (e.g., Bleed 1986; Bousman 1994; Kuhn 1995).

This part of the research proceeds in two phases. First, a chain of infer-

ences links reconstructed environments (including the Rockies) to inferred

late Paleoindian land use strategies (residential versus logistical) and ulti-

INTRODUCTION 3

1.1 Colorado-Utah project area, showing locations of Rocky Mountains, Great Plains,

Colorado Plateau, and Great Basin.

mately to inferred projectile point characteristics. Second, projectile point

technology is investigated directly in the Colorado-Utah assemblage, and

the results are compared to those obtained through inference alone. If the re-

sults converge, the land use strategies derived inferentially are probably accurate;

if they do not, hypotheses must be offered to account for the discrepancy.

The remainder of this introductory chapter delves more deeply into vari-

ous aspects of the project. First, a survey of previous late Paleoindian–oriented