CONVERSATION (resource books for teachers OXFORD)

Bạn đang xem bản rút gọn của tài liệu. Xem và tải ngay bản đầy đủ của tài liệu tại đây (33.37 MB, 158 trang )

RESOURCE

BCDKS FOR

TEACHERS

seies

edinr

ALAN MALEY

CtlNUERSATI(lN

Rob Nolasco &

Lois Arthur

Oxford University Press

Oxford Uoiveniry Press

Walton Stre€t, Oxford OX2 6DP

Ozlotd New Yoth

.*hett Au.hlind

Cahu\o

Banghoh Bombat

Ca?e Torun Dar es

Salaan Delhi

Fbence Hong Kong Istanbul Karo.hi

Kuala

Lmpu Madrat Madid

Mehoume

llenco City Nd;robi Pais Sinsaporc

Taipei Tohyo Toftnro

and associated companies in

B&lin lbadan

Oxford and Oxlod

ISBN 0 19 437096

Engh,

are trade

mark of Oxford Univenity

press.

I

e Oxford Universiry

Press 1987

Fi.st published 1987

Eighd impression 1995

.{ll rights reserved- No pan of this publication may be reproduced,

saored in a retrieval system, or Eansmitted, in any form or by any

means, elecEonic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

'*ithout the prior q,Titten permission of Oxford Universiry

Press,

with the sole exception of photocopying carried our under rh€

conditions described below.

This book is sold subjed ro rhe condirion rhar ir shall not, by way of

trade or othenrise, b€ lent. re-sold. hired our. or otherwise circulated

\r'iihout fie publisher's pior consenr in any form of birding or cover

other than that in which ir is published and withour a similar condirion

mcluding thrs condruon beLng irnposed on the suhrequent purchaser

Photocopying

The Publisher Sranrs permission for the phoaocopying of rhose

pages marked 'photocopiable' according to rhe following

conditions. Individual purchasers may male copies for iheir

om use or for use by ciasses rhey leach. Schoot purchasen

may make copies for use by rhet StaII and srudenrs, bur rlis

pemission does oot extend to eddirionai schools or branches.

ID no circurrsEnces may any pan of this bbok lte photocopied

S€t by Katerprint Tlpesetting Services, Oxford

Printed in Hong Kong

I

,.I

4

I

Acknowledgements

.-t

I

it

i-t

rl

ll

,.{

J

'l

-1

-,1

"l

I

I

I

-.J

i

i

I

.l

I

I

I

_l

-t

I

-l I

I

I

I

j

I

I

The publishers would like to thank the following for their

permission to use copyright material:

Nathaniel Altman and Thorsons Publishing Group Limited for an

exract from The Palmistry WorhDoo& (1984); Charles Handy and

BBC Publications for an extract from Taking Sneh - Being FifA in

tlp Eightbs (1983); Donald Norfolk and Michael Joseph Ltd. for an

extrect from Fareuell to Fatiguc (1985); Oxford Universiry Press for

an extract from the English Languge TeachingJoutul,Yol. 4012

(April 1986); Gordon Wells and Cambridge Univenity Press for an

extract from Leaning Thraryh Inuracrioa (1981).

I

t

1

l

Contents

The authors and series editor

Foreword

Introduction

I

Towards a classroom aPProach

l5

2

Controlledactivities

zt

Lezel

Actioity

Approx time

Desciption

(minutes)

I

Chain names

2

Name bingo

Beginner to

Advanced

5-t0

Beginner to

l0-15

and above

Guess who?

Elementary to

Elementary

Sounds English

Beginner to

Advanced

Introducing students to

24

Students find out more

about each other.

Students ask questions

in order to establish a

person's identity.

25

l0-15

Getting students'

tongues around English

27

To help students repeat

a dialogue.

Giving students simple

oral practice tlrough

dialogue repetition.

To make a recording

after listening to a taped

model.

Building up students'

confidenceHow different language

is used for the same

function.

To cue a dialogue so that

students have to listen to

I5-20

l5-20

Intermediate

5

24

each other (larger

classes).

Elementary

Find someone

who . .

Introducing students to

each other.

26

sounds.

8

Look and speak

Beginner to

I5-20

Listen and speak

Intermediate

Beginner to

Elementary

l5-20

Listen and record

Elemenfarv

rt20

and above

Shadow reading

l0 \7ho

do you

think. . .?

Beginner to

Advanced

10-15

Upper

intermediate to

2c_25

Advanced

Do you come here

often?

Elementary

and above

l0-15

what the other speaker says.

28

29

29

30

3l

32

game Elementary 10-15

and above

13 Who said it?

Intermediate 15-20

and above

14 Split exchanges Elemenrary l0-I5

and above

15 Anyone for tennis? Elementary to 5-10

Lower

12

The phone

Controlled practice of

telephone conversadons.

Inrerpredng and

attributing urterances.

Focusing on exchange

structure.

Practice with gaing ro to

express the future.

34

35

36

39

intermediate

16

l7

Is

thatright?

Elementary 10-15

Dialogue

fill-in

Inrermediare

and

l8

The besr years

my life

of

19 Experiences

40

Pet

hates

2l Theolddays

above

10-15

producing

4l

Practice in

more than minimal

responses.

Elementary I0-15

Practice in the

and

past forms.

above

Elementary 15-20

and

20

gambits.

Recognizing

and above

above

practice in the

perfect tense.

above

I loae,I

Elementary 10-15

and

Intermediare

15-20

simple

42

present

42

Practice in forrns such

hate, etc.

Practice in

as

43

uedro.

44

hypothetical

44

hypotherical

15

Pracdce in

u:ould.

hyporhetical

46

Practice ir

forms.

quesdon

47

and above

22 Ifonly...

Intermediate

and

above

lO-15

rien Intermediate 15-20

and above

24 Cheat

Intermediate 10-15

and above

25 Could I ask you a

Elementary 15-20

few questions, and above

23

Je ne regrette

Practice in

zuould.

Practice in

ztould.

please?

3 Awareness activities

26 Encouraging noises Elementary 15-20

- and above

27

Keep

talking

Elementary 10-15

above

and

28 Encouragement Intermediate 10-15

and above

29 Repetition

5l

Expressions which

encourage the other

speaker to condnuerVays in which fiIlers

52

53

can contribute to an

rmpression offluency.

Expressions which

encourage lhe speaker to

54

say more.

Upper

to

Advanced

intermediate

15-20

Different uses to which

repetition can be put in

tlre spoken language.

55

30

As I was saying

3l

Gestures

32

Follow me

33

Sound

Upper

intermediate to

Advanced

Intermediate

20_25

tlem.

Using gestures as

reinforcement of what is

being said. (video task)

58

t5-20

Repetition of certain

words and phrases, and

body language. (video

task)

60

Extra-lingui stic clues to

60

and above

off

Elementary

l0

help students understand

and interpret what is being

said. (video task)

and above

34

Sound only

35

\7hat's next?

Elementary

20 (max.)

A smiling face?

Intermediate

a feel

for

6l

l5 (max.)

Practice in following

extended conversation.

(video task)

62

20-25

To raise sensitivity in

students to body

63

and above

35

Developing

voice quality. (video

task)

and above

Elementary

57

l0

and above

Elementary

Types of interruption

and how to deal with

and above

language.

37

The message is

Intermediate

t5-20

and above

38

I want

39

I haven't got any ice!

a blue onel

Elementary to

Intermediate

Intermediate

l0-15

5-10

and above

40

Intermediate

Take that!

15-20

and above

4l

is a question?

.This

42

43

20-25

English.

Stress practice in the

context of a dri.ll.

Shifting stress in a

prompted dialogue,

altering meaning.

Making students aware

of sentence stress.

How intonation can

alter meaning.

64

67

68

69

70

and above

-

Same words

different message

True or false?

,14 Similariries and

differences

Upper

intermediate

Recognizing the

function ofgestures in

Intermediate to

15-20

Advanced

Upper

intermediate to

Advanced

Upper

intermediate to

Advanced

25-30

2U25

Ways in which the

rneaning of an utterance

can be altered by

changing the intonation.

Ways in which native

speakers try to be pol.ite

in social encounters.

Social behaviour in the

target language.

70

73

75

f

I

45

Culture shock!

25-30

Intermediate

and above

Problems people

encounter when tiey

have to live in a new

'

country.

:

!

4

Fluency activities

46

I hated Maths

you?

47

- did

Habits

79

25-30

83

30-35

Introducing students to

fluency activities.

Sharing opinions.

2r30

Sharing opinions.

86

Intermediate to

30-35

Uppet

intermediate

Intermediate

Telling each other about

emotions.

20 (max.)

Talking about likes and

dislikes.

Getting students to

explore their life style.

Talking about fears.

Elementary

and above

Intermediate

84

i

l

I

Intermediate

Famiiy life

I

J't

I

and above

48

I

II

and above

Emotions

50

A coma

kit

and above

5l How much

energy

do you have?

52

Emotional match

Intermediate

30-40

and above

Elementary

20_25

88

90

and above

53

Exchange

EIementary

20

(min.)

and above

55

56

Have you heard

Elementary

of . .

and above

.?

35-40

It's all in your hands

Uppe.

35-40

The best

intermediate to

Advanced

Elementary to

20-25

Lower

intermediate

57

Eureka!

Intermediate

30-35

and above

58

Time

Time capsule

A just punishment

5l

Future shock

Intermediate

Advanced

Intermediate

Advanced

to

30-35

to

25-35

Uppet

30-35

intermediate to

Advanced

Intermediate

Advanced

to

30-35

Finding out about each

otier by asking

questions.

9l

Cross-cultural exchange

in mixed nationality

groups.

Talking about personal

characteristics, and

92

palmistry.

Introducing students to

ranking activities.

Promoting discussion

about inventions.

Justifying and

explaining preferences.

Things students value in

their daily lives.

Considering the extent

to which punishments

fit the crime.

Discussing priorities for

the future.

{

i

I

I

93

96

'97

I

I

i

97

99

i

100

i

l0l

l

bridge

62

The

63

From what I

remember

64

A dream

Upper

30-35

inrermediate to

Advanced

Elementary 2C_25

and above

classroom Elementary

and

65

Plan your

time

above

30-35

Intermediate 30-35

and

above

Deciding on individual

responsibility for a

tragedy.

Discussing the results of

a simple memory

experiment.

Carrying out a design

task togetherConsidering ways in

which students can learn

English outside the

102

104

l(X

105

classroom.

56

My ideal

book

phrase- Elementary 35-40

and above

67

Building

a

model Intermediare 25-30

and above

68 I'll give you . . .

Elementary

above

Upper

intermediate to

Advanced

and

69 Airport

70

7l

Attitudes to gifts

giving

Ifho's

the

72 Gifts

to

Working together

produce and evaluate

phrase-books.

and Intermediate

and

above

boss? Intermediate

and above

Elementary

Evaluating how

effectively students are

able to perform a given

task.

2135

Students buy and sell

(2 lessons) things.

30-35 A conflict situation in

which students have to

decide what to do.

25-30 A cross-cultural

discussion about gifts

and giving.

35-40 Discussing the role of

secretaries at work.

2540

Talking about gifts.

106

107

108

109

II

I

112

I 14

and above

73

Love

story

Intermediate 4045

and

5

above

well-known

Using a

story as a stimulus for

students to produce

their own.

Feedback

Task

I

Task

2

Task

3

Task 4

I 15

t17

Elementary

Advanced

Elementary

Advanced

Elementary

Advanced

Elementary

Advanced

to

to

Students look closely at

the language they use.

125

Encouraging

126

expressrons.

hesitation

to

Fillers and

devices.

to

128

Strategies we use to

keep a conversation going.

127

.l

I

Task

5

Task 6

Task

7

Task

8

Task

9

Task l0

Task

ll

Story-telling devices.

t29

How we make and

respond to suggestions in

order to encourage people

to be constructive.

Ways in which we seek

and give opinions.

Ways of introducing

polite disagreement.

Giving a talk.

130

t34

I

How we use

comrnunication

strategies to carry on

speaking.

Students consider how

they behave in meedngs.

r35

-t

I

Intermediate

Patternsofinteraction

143

and above

within

Elementary to

Advanced

Elementary to

Advanced

Elemenmry to

Advanced

Elementary to

Advanced

Elementary to

Advanced

Elementary to

Advanced

Upper

intermediate

I

i

I

.t

.t

131

I

133

-t

.t

I

I4l

I

I

and above

Task

12

Bibliography

a

i

group.

I

,{

145

I

-l

{

1

I

-t

I

I

-t

I

The authors and

series editor

Rob Nolasco has been involved in English as a foreign language

since 1970. He was pan ofthe senior management ofThe

British Council managed ESP proiect at King Abdulaziz

University, Jeddah (1978-80). Between 1981 and 1983 he was a

Project Director with the Overseas Development Administration

in Angola, and wi*r The Cenre for British Teachers Ltd. in

Morocco (1933-85). He has also taught EFL to secondary and

adult srudents, at all levels, in the UK, Turkey, France, and

Spain. He is currently working as an EFL author and consultanr.

His books for students include *rree OUP courses: lZOlZ./

(Window on the WorlQ, Ameican IVOIV!' and Streetwise.

Lois Arthur started her career with the Centre for British

Ltd. in West Germany. In 1979 she took up the post of

Senior Tutor at The Bell School of I-anguages at Cambridge.

Between 1983 and 1985 she was the Deputy Project Director

with The Centre for British Teachers Ltd. in Morocco. She is

currently Director of UK Schools and Young I-eamers for The

Teachers

Bell Language Schools.

Alan Maley worked for The British Council from 1962 to 1988'

serving as English l-anguage Offrcer in Yugoslavia, Ghana, Italy'.

France, and China, and as Regronal Representadve in South

India (Madras). From 1988-1993 he was Director-General of

the Bell Educational Trust, Cambndge. He is currenrly Senior

Fellow in the Depanment of English I-anguage and Literature of

the National University of Singapore. Among his publications

ate: Quartet (wirh Frangoise Grellet and !(rim Velsing)' Be1'ozd

ll'ords, Sounds Interesting, Sounds Intriguing, Words' Vaiations on o

Theme, Literature (in this series), and Drama Techniques in

Language Learning (all with Alan Dufi, The Mind's Eye (with

Frangoise Grellet and AIan Duff), Leaming to Listen and Poem

into Poem (wirh Sandra Moulding), and Shon and Sweer. He is

also Series Editor for the Oxford Supplementary Skills series.

Foreword

The distinction between accuracy and fluency is now a familiar one.

Almost as familiar is the further distinction between fluency and

appropriacy. To be accurate is not necessarily to be fluent. And to

be fluent is not necessarily ro be appropriate in a given set of

circumstances.

In this book the authors make a further distinction: between

speaking skills and conversation skills. They conrend thal there are

skills specific to conversation which make it easier for people to talk

to each other informally, and that these do not overlap a hundred

per cent with the skills involved in fluent speaking. Being able to

speak reasonably correct and even fluent English is one thing.

Being able to engage in on-going, interactive, mentally satisfying

conversation is anorher. This is not to deny that speaking skills are

necessary for conversation; simply that they are not alone sufficient

for successful conversation to take place.

It is these specific conversational skills which the book sets out to

cover. In order to do so, the authors first examine in the

introduction what ir is that native speakers do when they 'make

conversation'. They then use this inforrnation as the basis for the

tasks and activities in the remainder of the book.

Two obvious, but nevertheless frequently neglected facts about

conversations, are that they involve at leasr rwo people, and that the

pardcipants in a conversadon cannot talk simultaneously all rhe

time. Unless they agree to share the speaking time, listen, react,

and attend to each other, the conversation dies.

This is in contrast to a view of speaking, which is often handled as if

it were the only factor ofimportance. Absorption in speaking,

without attending to the other, can only lead to surreal parallel

monologues, such as we encounter in Pinter. The mutual,

interdependenr, interactive nature ofconversation is given special

emphasis in tle sections on Az.ucreness actioities and Feedbach

actizities. A series of tasks is developed here to sharpen the

students' awareness and observation both of themselves and of

others. The rmportance given to equipping the students with tools

to evaluate dreir own performance tboth in dre conversations and in

tieir own learning) is especially welcome.

Conaersation is rnique in its insistence on the need to teach

conversational skills. The imponance ir gives to developing a

sensitivity to fellow participants in conversarions is likewise highly

original. Above all it offers a rich and varied selection ofactivities

and msks to draw upon.

It will be welcomed by all teachers interested in developing further

the teaching of this important aspect of oral expression.

Alan Maley

Introduction

Foreign language teachers often tend to assume that conversation in

the language classroom involves nothing more than putting into

practice the grammar and vocabulary skills taught elsewhere in the

course. So, the 'conversation class'may turn out to include

everything from mechanical drills to task-based problem-solving

activities. It is true that both tlese types of activity may, to some

extent at least, help students develop the skill of taking part in

conversation. But, if we want to teach conversation well, we need to

know something about what native speakers do when they have

conversations. This information can then help us to develop

appropriate materials and techniques for teaching purposes. In this

section therefore, we shall be looking at the characteristics of

native-speaker conversation in order to provide a rationale for the

practical exercises which follow in the remainder of the book.

What is conversation?

People sometimes use the term 'conversation' to mean any spoken

encounter or interaction. In this book however, 'conversation'

refers to a dme when two or more people have the right to talk or

listen without having to follow a fixed schedule, such as an agenda.

In conversation everyone can have something to say and anyone can

speak at any time. In everyday l-ife we sometimes refer to

conversation as 'chat' and the focus of the book is on this type of

spoken interaction, rather than on more formal, plamed occasions

for speaking, such as meetings.

The functions of conversation

The purposes of conversation incllrde t}te exchange of information;

the creation and maintenalce of social relationships such as

friendship; the negotiation of starus and social roles, as well as

deciding on and carrying out joint actions. Conversation therefore

has many functions, although its prirnary purpose i-n our own

language is probably social.

The units of conversation

The basic unit of conversation is an exchange. An exchange consists

of two moves (an initiating move and a response). Each move can

also be called a turn, and a turn can be taken without using words,

e.g. by a nod of the head. So for this dialogue the move and

exchange structure can be illustrated in the following way:

A

B

Jane.

Yes?

A

B

A

A

Tum

Could I borrow your bike, please?

Sure, it's in the garage.

Thanks very much.

1

lsolicit: calrj

Turn 3

Tum 5

Isolic : reguestl

[Acknowledge:

thankl

'Thanks very

'Could I bonow

your bike, please?'

'Jan€.'

mrrch.'

B

Iu.r'

Tum 4

2

lcivet availabld

lciue: conpvr

'Sure, it's in the

'Yes?'

garage.'

Exchange

1

Figurc 1 Az illustration of moue and exchaflge structure

{--

2

------------>

€xchange

3

,---------------

We can give a function to each move, e.g. request, acknowledge.

This may not be easy, and to do so we need to take account of

factors such as who the speakers are, where and when the

conversation occurs, as well as the position of the move in the

stream of speech.

Notice that an exchange, or a series ofexchanges, are nol

necessarily tie same thing as a conversation. The following is an

example of al exchange:

A Hi!

B HiI

The second example conlains lwo exchanges, but it is not a

conversation because the two speakers wanr to finish their business

as q'.'ickly as Possible'

A How much are the oranges?

B Eighteen pence each, madam.

A I'll have two, please.

B That's thirty-six

pence!

Conversation is open-ended and has the potential to develop in any

way. It is possible that the second example could contain a

conversation if the speakers decided to ralk about the price of

oranges. They may do riis in order to get a discount, or to develop a

social relationship, and the potential is always there in real life.

Unfonunately, many students never have the confidence or

INTRODUCTION

opportunity to go beyond simple exchanges like dre one above, and

one of the main objectives of this book is to introduce exercises

which allow students to develop tle ability to initiate and sustain

conversadon.

What do native speakers do in

conversation?

Conversation is such a natural part ofour lives that many people are

not conscious ofwhat happens within it. However, conversadon

follows certain rules which can be described. For example, when

we look at norma.l conversation we notice that:

usually only one person speaks at a rimel

the speakers changel

the length of any contriburion variesl

there are techniques for allowing the other pany or panies to

speak;

nei*rer the content nor the amount ofwhat we say is specified in

advance.

-

Conversation analysis seeks to explain how this occurs, and the aim

ofthe secdons which follow is to make the readers sensitive to the

main issues from a teaching point of view.

The co-operative principle

Normal conversations proceed so smoothly because we co-op€rate

in them. Grice (1975) has described four maxims or principles

which develop co-operative behaviour. These are:

The maxim of quality

Make your contribution one that is true. Specifcally:

a. Do not say what you believe to be false.

b. Do not say anything for which you lack adequate evidence.

The.maxim of quantity

Make your contribution just as informative as required and no

more.

The maxim of relation

Make your conribution relevant and timely.

The maxim of manner

Avoid obscurity and ambiguity.

Readers will realize that these maxims are often broken and, when

this happens, native speakers work harder to get at the underlying

meamng, e.g.

A How did you fnd the play?

B The lighting was good.

By choosing not to be as informative as required, B is probably

suggesting the plav is not worth commenting on. A lot of the

material written for teaching English as a foreign language is

deliberatel-v free of such ambiguity. This means that students have

problems later in conversational situations where the ma-.'

discourse may be one solution.

These maxims may also be observed differently in different

cultures, so we need to tell students ifthel'are saying too much or

too little without realizing it.

The making of meaning

When we speak we make promises, give advice or praise, issue

threats, etc. Some linguists refer to individual moves as speech acts'

Each of the following are examples ofspeech acts and we can try to

allocate a specific function to each example:

- Tum left at the next slreet. (Instruction?)

- Inoest in Crescent Ltfe. (Advice?)

-

Keep off the

grass. (Order?)

However, we need to know the context of the example to give it a

function pith anv certaintl', and it is eas-v to think ofsiruarions in

which the examples above might have a different function from the

one sho*'n. In conversadons the relationship betu'een the speaker

and the listener will have an important effect on how the listener

understands the particular speech act. For example, the wav in

which we hear and respond to a statement such as 1'oe lost my

ztallet, may well depend on whether we think the person is trying to

obtain money under false pretences or not! There is no room to

enter into a full discussion ofdiscourse analysis, but rhe following

issues are particularly relevant to the teaching of conversadon.

Most speech acts have more than one function, e.g. when we say to

a waitress, The music is rather lozl, rve are simultaneousll' reporting

that we cannot hear ourselves speak, and also complain.ing and

asking the waitress to do something about it. Any approach that

leads students to equate one particular language form with one

panicular language function, will lead to misunderstandings in

conversation because an imponant requirement for success is being

able to interpret intended speech acts correctly. There is also a need

to help students begin to become sensitive to why a speaker chose a

panicular speech act, e.g. by setting a listening usk which asks

students to comment on tlte purpose of what they hear - is it meant

as a challenge, a defence? etc.

INTRODT](:TION

Adjacency

The two moves in an exchange are related to each other through the

use ofadjacency pairs. These are utterances produced by two

successive speakers in which the second utterance can be identified

as being related to the first. Some examples ofadiacency pairs are:

I A Hello! (Greeting-Greetrng)

B HiI

2h

Dinner's ready ! (Call-Answer)

B Coming.

3A Is this yours? (Question-Answer)

B No.

In some cases we can predict the second part of a pair from t}re first.

As in example l, a greeting is normally followed by a greeting. In

otler cases there are a variely ofoptions. For example, a complaint

might be followed by an apology or a justification. Teachers need to

think about ways of developing appropriate second pans to

adjacency pairs from the srarr. For example, many drills require

students to reply to yes/no questions with 'yes' or 'no', plus a

repetition of the verb. We therefore get exchanges like:

A Are these cakes fresh?

B Yes, they are.

What students do not often get are opportunities to practise other

options, such as:

A Are these cakes fresh?

B I bought them this morning. Help yourself.

Even worse is the tendency to encourage students to produce

isolated sentences containing a target sfucture, e.g. If I had

f10,000 I'd buy a car. Unless we get away from quesaion-answerquesdon-answer sequences and the production of sentences without

either stimulus or response, students will always appear to be flat

and unresponsive in conversation because a minimal answer does

nothing to drive the conversation forward. !7e shall look at how

this might be done through conuolled activities in Chapter 2.

Turn taking

As native speakers we find it relatively easy and natural to know

who is to speak, when, and for how long. But rhis skill is nor

automatically transferred to a foreign language. Many students

have great difficulty in getring into a conversarion, knowing when

to give up their turn to others, and in bringing a conversation to a

close- In order for conversation to work smoothly, all participants

have to be alert to signals that a speaker is about to finish his or her

turn, and be able to come in witl a contribution which 6ts the

direction in which the conversation is moving. We need to rrain

students to sense when someone is about to finish. Falling

intonadon is ofien a signal for rhis.

It would also be useful for students to realize that quesrions like,

Did. anyone watch the football last nigit? funcdon as a general

invitation to someone Io develop a conversation. Foreigners also

sometimes lose their turn because they hesirate in order to find rhe

right word. Teaching our students expressions \ke,lVait, there's

mare, or That's not a/1, as well as fillers and hesitat.ion devices such

zs Enn . . .,Well . . .,so jou can gucss u:hat happercd . . ., erc. will

help them to keep going. Finally, ir is well worth looking ar wal s in

which we initiate and build on what otlers have said such as ?n&cr's

lihe what happened to me . . . and Dil I tell3tou about when . . .?, so

that students can make appropriate contributions. Some relevant

act.ivities can be found in Chapters 3 and 5.

Openings and closings

The devices used for opening and closing differenl conversadons

are very similar. Many conversadons start with adjacency pairs

designed to attract attendon, such as:

I A Have you got a light?

B Sure.

2 A Gosh it's hot in here today.

B I'm used to it.

Openings such as these allow further talk once the other pcrson's

attention has been obtained. Many foreign students use opcnings

that make them sound too direct and intrusive, for example, by

asking a very direct question. Closing too presents a problem when

the sudden introduction of a 6nal move like, Goodbye makes the

foreigner sound rude. Native speakers wi.ll tend to negotiate the end

ofa conversation so that nobody is left talking, and you will hear

expressions like:

- OKthen...

- Right. .

- \Vell, Inppose...

- Erm, I'm afraid . .

- I'oe got to go ttou;- I'll let you get bach to your writing.

- So I'll see you next weeh.

.

.

It is worth pointing these out. Nadve speakers sometimes try to cut

only producing a minimal response or even

saying nothing at all, but neither strategy is recommended for

students of English.

a conversadon short by

(

(

(

{

(

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

a

rl

i

a

I

|l

a

a

tl

I

!.

L

INTRODUCTION

ll

r oprcs

Different cultures talk about different things in their everyday

lives. Nadve speakers are very aware of what they should and

should not talk about with specific categories ofpeople in dteir own

language, but the rules may be different in a foreign language. Both

teachers and students need to develop a sense of'taboo' subiects if

they are to avoid offence.

Male and female differences in

conversauon

Current research reveals interesting sex differences in conversation

among native speakers. Women, for example, are more Iikely to

show an interest in personal details than men. They are also better

lsteners and more likely to help the person they are speaking to

develop a topic, by asking information questions and making

encouraging remarks and gestures. However, men are more

reluctant to disclose personal information. They prefer it when

there is a purpose for the conversation and they would rather talk

about outside topics, e.g. games, hobbies, politics, cars, etc. t}tan

themselves. This may influence our choice of topic.

Simplification in informal speech

There are many foreign students who pronounce the ildividual

sounds and words of English beautifu.lly but who still sound very

foreign. The reason is that in English the sound quality of a word,

particulady the vowels and certain consonants, changes depending

on whether the word is said in isolation or as pan ofa continuous

stream of words. Some of this is a result of simplification of

informal speech. One important reason for simplification is that

English is a stress-dmed language. rJ hen we speak, all the stressed

syllables in our sentences tend te come at roughly similar intervals

of time. This means that the following sentences (taken from

Broughton et al 1978), when spoken by the same speaker in normal

circumstances, would take the same amount of time to say, even

though they contain different numbers ofwords or syllables.

I lboughtadog.

2 lt's a dogl bought.

3 But it's a dog thatl bought.

They are the same length when spoken because they contain the

same number of suessed syllables ( dog and bought)- This means that

the unstressed syllables have to be squeezed il and the vowels,

which are in unstressed syllables, very often become the neutral or

t2

{

INTRODUCTION

weak vowel, or'schwa'which is represented by the symbol [:].

This is the rnost common sound in spoken English and the use of

weak forms means a native speaker will tend to say:

-

Itwas

him.

/rt waz hrm/ not /rt woz hrm,/

Giae it to me. /grv rt te mi/ not /grv rt tu: mi/

Elision, which is the 'missing out' of a consonant or vowel, or

is also very common. A native speaker would tend to say:

both,

/'f: : st'Ori :/ for'first three'.

For foreigners (panicularly those whose native language is

syllabus-timed, e.g. French), the tendency is to give each pan of

a word the same value and this can have a wearying effect on the

native speaker listener, who will, as a result, be less likely to remain

sympathetic and interested. It is therefore worth pointing out weak

forms from the start for recognition and production.

/'fs :s'0ri:/ not

I

I

I

t

t

I

I

I

t

a

a

I

F

Stress and

intonation

Good conversationalists use stress and intonation to keep

conversations going. A fall on words like 'OK' or 'So', often serves

to show tttal we are about to change the subject. A rise on 'really'is

a way ofshowing interest. All ofthese are important signals and it is

worth pointing these out to students when they occur so thar they

start iistening for them. A wide voice range is also more likely to

keep a listener interested than a monotone. This can be difficult for

students whose native language has a narrow voice range, and for

rhese students addirional sensidviry training may be needed.

Students also need to realize that the wrong intonation can Iead to

misunderstanding. For example, researchers found that Pakistani

ladies who were serving in the canteen of Heathrow often got a

hostile reacdon by pronouncing the word 'gravy' r.r.'ith a falling

intonation, rather tlan the rise wh.ich would be polite in British

English.

Gesture and body language

Vh.ile it is uue that speakers of English do not use as much gesture

as people in some other cultures, e.g. Italians, they do use their

hands to emphasize a point. The positioning ofthe body also has an

effect on the listener. Sitting on the edge ofa seat may be seen as

being aggressive. Slumping in it is a sign of boredom, and even

where we do not mean it this may be how it comes across. In some

cultures people also smnd very close to tiose they are talking to and

many Americans report discomfort when faced with MiddleEasterners who tend to value proximity and touch. Body language

is a complicated area but it is worth observing your students and

giving them feedback on how they appear to others.

t

I

)

)

l

I

)

INTRODUCTION

Summary

Teachers need Io be aware of the characterisdcs of nadve-speaker

performance in conversation if they are to teach conversation

effectively. They also need to consider which of the funcdons of

conversation are most relevant to the students. These will vary

according to Ievel and needs, but most general purpose students

would want to use English to

- give and receive informarion;

- collaborate in doing something;

-

share personal experiences and opinions wirh a view to building

social relationships.

Students will not be able ro do rhese things by ralking clozt

conversalion, and the stress in this book is lea rning by doing ldtro:ugh

activities which give students practice in a pattern of interaction

that is as close as possible to what competent nadve speakers do in

real life. This is the purpose of the F lumcy actiztities in Chapter 4.

However we recognize that students need guidance and support in

the early stages and this is the rationale behind rhe Controlled

actiz;ities in Chapter 2. We also believe that the performance of the

students can be improved by increasing their sensitivity to the way

that conversation works, and the tasks in Chapter 3 are mostly

aimed at developing awareness. The other vital ingredient is

feedback. Studenrs need to be able to assess *Ieir progress so that it

is possible to identify areas for further practice, and this issue is

rreated in Chapter 5.

Finally, the key to the smooth operation of task-based fluency work

is the effecrive managemenr of the materials, of rhe students, and of

the classroom environment. The crv from rnan,'- students'I just

want conversation Iessons" or'I iust want to practise ralking; I

know the grammar', suggesrs that conversation lessons are

somehow easier to prepare and teach, are inferior in sutus to 'the

grammar lesson', and so on. Yet many teachers will know to therr

cost how often the conversation lesson just does not quite work. In

Chapter I we look at how the activities in the book can be used and

put together to provide a coherent and purposeful approach. Above

all we hope that users of the book will find the approach suggested

pracdcal, useful, and interesting enough to develop ideas along

similar lines.

l5

I Towards a classroom

approach

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to give a briefaccount ofhow the

activities which can be found in chapters 2 to 5 can be combined to

provide a coherent approach to the teaching ofconvenation.

Ahhough many students say that their main purpose in learning

English is to be able to speak it, many students will not talk readily

in class, and the'discussion lesson' in which rhe teacher does most

of the talking is still too prevalent. Ifyou 6nd that this is happenirg

consistently then you should pause and ask yourself the following

questions:

I

Do I make an effon to prepare students for the discussion or

fluency activity?

Preparation is a vital ingredient for success. Students need to be

orientated to the topic, and an instruction like'Let's talk about

euthanasia' rarely works. Some of the fluency tasks in Chapter 4

have pre-tasks built in but some students may need more

orientation to a topic than others for cultural or linguisdc reasons.

Some simple techniques which can be used to prepare students for

a

particular topic include:

- The use of audio visual ards to atouse inleresl.

- A general orientation to the topic by means of a shon text,

questionnaire, series of statemenls for discussion and

modification, a video extract, etc. The only rule is that the pretask should never be too long.

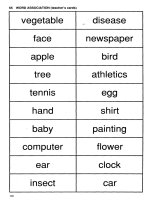

- Exercises to build up the vocabulary ne€ded for a task. This can

include matching words to pictures, putting words from a list

inro different categories, learning words from lists, etc.

2 Do students klow what is expected of them?

Students may need to be orientated to the task itselfso that they

know what is expected of them. For example, the insuuction to

'discuss' a topic may be meaningless to many students who do not

come from a culture where such discussion is a norma.l part of the

educational process. In some cases students may need training, and

this is discussed briefly later in this chapter. The general rule is to

formulate tasks in terms srudents can understand ald make sure