CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF SCHIZOPHRENIA - PART 8 docx

Bạn đang xem bản rút gọn của tài liệu. Xem và tải ngay bản đầy đủ của tài liệu tại đây (365.79 KB, 67 trang )

preexisting psychiatric disorder may increase vulnerability to the emergence or chronicity

of posttraumatic symptoms following exposure. Research to date supports the likely con

-

tribution of these, and other possible mechanisms, linking trauma exposure, schizophre

-

nia, and PTSD.

Several other contributory factors have also been hypothesized. For example, psy

-

chosis and associated treatment experiences (e.g., involuntary commitment) may them

-

selves represent DSM-IV-TR Criterion A traumas. The potential symptom overlap be

-

tween schizophrenia and PTSD (e.g., flashbacks being misinterpreted as hallucinations;

extreme avoidance and anhedonia interpreted as negative symptoms), may conflate the

apparent rates of PTSD in those diagnostic groups. Alternatively, PTSD associated with

psychotic symptoms may be misdiagnosed as a primary psychotic disorder.

Clients and advocacy groups often point to posttraumatic symptoms as among the

most troubling of these individuals’ life problems, and many U.S. states have prioritized

the development of “trauma-sensitive services” as a key reform to mental health and sub

-

stance abuse service systems. Major elements of trauma-sensitive services include (1) in

-

creased awareness by providers about trauma history and sequelae among clients; (2)

better understanding of special requirements of survivors; and (3) knowledge of trauma-

specific interventions for persons requiring such services. We discuss these three topics in

this chapter, and provide tools and useful references to increase mental health providers’

knowledge and competence in regard to trauma-related issues. Posttraumatic stress disor-

ders are among the most treatable of psychiatric syndromes, and it is important to recog-

nize and treat PTSD symptoms in clients with schizophrenia.

DEFINITIONS

Psychological trauma refers to the experience of an uncontrollable event perceived to

threaten a person’s sense of integrity or survival. A traumatic event is defined by DSM-IV-

TR as an event involving direct threat of death, severe bodily harm, or psychological in-

jury, which the person at the time finds intensely distressing (i.e., the person experiences

intense fear, helplessness, or horror). Common traumatic experiences include sexual and

physical assault, combat exposure, and the unexpected death of a loved one. Negative

psychiatric and health outcomes are associated with the total number of exposures to

traumatic events and with their intensity. Sexual assault and other forms of interpersonal

violence in which the victim suffers actual physical harm, along with childhood sexual

abuse, represent the forms of trauma most likely to lead to persistent psychiatric disor

-

ders, including PTSD. PTSD is defined by three types of symptoms: (1) reexperiencing the

trauma; (2) avoidance of trauma-related stimuli; and (3) overarousal. These symptoms

must be related to the index trauma and persist, or develop at least 1 month after expo

-

sure to that trauma. Examples of reexperiencing include intrusive, unwanted memories of

the event, nightmares, flashbacks, and distress when exposed to reminders of the trau

-

matic event (e.g., being in the vicinity of the traumatic event, meeting someone with simi

-

larities to the perpetrator). Avoidance symptoms include efforts to avoid thoughts, feel

-

ings, or activities related to the trauma; inability to recall important aspects of the

traumatic event; diminished interest in significant activities; detachment; restricted affect;

and a foreshortened sense of one’s own future. Overarousal symptoms include hypervig

-

ilance, exaggerated startle response, difficulty falling or staying asleep, difficulty concen

-

trating, and irritability or angry outbursts. DSM-IV-TR criteria require that a person

must have at least one intrusive, three avoidant, and two arousal symptoms to be diag

-

nosed with PTSD.

448 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

How do clients with both schizophrenia and PTSD present differently from those

with schizophrenia alone? First, it is important to recognize that most of these clients do

not spontaneously talk about their trauma experiences and related symptoms. Clinicians

generally believe that they know their client well enough to be aware when a particular

client has experienced a very adverse event. Thus, providers are often surprised when

they systematically inquire about trauma history in clients they have know for years, and

learn for the first time about traumatic events clients have experienced. The reality is that

a central feature of PTSD is avoidance. The last thing that most trauma survivors are

likely to do is to discuss spontaneously or describe past traumatic events, or associated

problems such as nightmares and avoidance (e.g., fear of going back to a setting where a

sexual assault occurred). Because clients with PTSD tend to appear more fearful,

avoidant, and distrustful of others, they are more difficult to engage. On average, they are

more likely to abuse substances (often to avoid memories of their traumatic experiences),

to experience revictimization, and to be assaultive toward others, including providers. In

general, clients with PTSD tend to be more impaired, low function, and symptomatic

than individuals without PTSD.

For example, one client reported believing that others could see into his mind, and he

frequently heard persecutory voices when he was out in public, which made him very

wary of leaving his house. Only when he was assessed for PTSD symptoms did his pro

-

viders become aware that the voices referred both to childhood incidents of being sexu-

ally abused and his own subsequent abuse of other, younger children. He believed that

people on the street knew about his past actions and were highly critical of him. The

voices were a form of expressing guilt and shame (common among abuse survivors), and

of reexperiencing the trauma. What was somewhat unusual in terms of PTSD (although

not unknown in severe cases) was that this client utilized psychotic mechanisms to ex-

press these symptoms and associated distorted cognitions. However, once he was treated

for PTSD, the voices essentially disappeared, and the client became less psychotic. An-

other client frequently relapsed into substance abuse when exposed to reminders of her

past trauma (so-called “triggers”). These slips also tended to lead to more general de-

creases in her ability to function independently, including unstable housing, inability to

hold a job, and frequent rehospitalizations. Treatment for PTSD helped this client de

-

velop alternative strategies to alcohol use in response to trauma-related stressors, and a

period of relative stability followed. The trauma-related problems described in these cli

-

ents represent either the primary or associated symptoms of PTSD. An understanding of

this disorder is crucial to clinicians’ ability to recognize the behaviors, attitudes, and

symptoms that people with schizophrenia and PTSD present.

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS SYNDROMES:

THE EVOLUTION OF THE CONCEPT

Recognition of the psychiatric complications associated with extreme forms of trauma

exposure has a long history, dating back at least to the U.S. Civil War. In the last half of

the 19th century, the concept of Da Costa syndrome, or irritable heart, appeared in the

medical literature. Seen first in combat veterans, it was characterized by anxiety (fearful

-

ness, chest pain mimicking heart attack), extreme fatigue, and arousal symptoms (palpi

-

tations, sweating). By the end of the 19th century, Breuer and Freud had recognized and

described the role of trauma in various neurotic disorders, particularly so-called “hyste

-

ria,” and Freud continued for many years to theorize about the role of traumatic events

in personality formation and disruption of functioning. Throughout the 20th century,

43. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Syndromes 449

posttraumatic reactions were recognized in psychiatry and military medicine, and gener

-

ally conceptualized under various labels that suggested organic etiologies (e.g., “shell

shock” in World War I, and “combat fatigue” in World War II). Psychiatry has also long

recognized that civilian traumas (e.g., dramatic changes in life circumstances; car acci

-

dents) can produce similar emotional reactions.

In more recent years, the psychological and psychophysiological components of

posttraumatic disorders have been better characterized through empirical studies, and the

affective, cognitive, and interpersonal alterations associated with trauma exposure have

been extensively researched and described in the literature. Neuroimaging techniques

have more recently allowed the field to examine the neurobiological alterations in persons

who develop PTSD, including hippocampal changes (atrophy) and alterations in amygdala

function. Both lines of research have been associated with advances in treating PTSD. A

variety of psychotherapeutic interventions (primarily based on cognitive-behavioral tech

-

niques) have become well established through multiple clinical trials, and effective treat

-

ments are available for a variety of trauma populations, including children, combat veterans,

sexual assault survivors, and women who experienced abuse in childhood. Biological

treatments, which build on the similarities between the neurobiology of PTSD and

depression, have also shown utility in reducing symptoms. Systematic reviews of these

treatments and their relative efficacy are available (see References and Recommended

Readings). However, until very recently, no proven treatments for clients with both

schizophrenia spectrum disorders and PTSD have been available. Several clinical research

groups are now actively addressing this gap in services, and promising treatment models

are described below.

TRAUMA, SCHIZOPHRENIA, AND PTSD

Unfortunately, until the last decade, theory and practice regarding severe mental illnesses,

such as schizophrenia, and posttraumatic stress syndromes were quite separate and dis-

tinct. Much of the seminal work on trauma-related psychiatric disorders focused on combat-

related stress responses, and scant research—and almost no treatment models in the

field—explicitly considered the intersection of trauma-related disorders with other major

DSM Axis I disorders. Following the inclusion of PTSD as a diagnosis in DSM-III, re

-

search on trauma-related disorders accelerated. The field became increasingly aware that

many forms of civilian trauma exposure, including childhood physical and sexual abuse,

are not only common events but also are frequently comorbid and possible contributory

factors in a variety of other psychiatric disorders. Exposure to traumatic events in general

population studies is associated with increased psychiatric morbidity, substance abuse, in

-

creased medical utilization, and generally poor health and functional outcomes. These re

-

lationships are often mediated by PTSD.

TRAUMA EXPOSURE AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

Limited systematic research has investigated trauma exposure in clients with schizophre

-

nia spectrum disorders. Most studies have looked at the broader category of severe men

-

tal illness (typically including both schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders, and

chronic and disabling major depression). These studies have reported overwhelmingly

high levels of trauma exposure, both prior to illness onset and throughout the course of

illness. In those few studies looking specifically at clients with schizophrenia, the same re

-

450 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

lationships are evident. For example, in a recently completed study of adverse childhood

events in a large sample of clients with schizophrenia receiving public mental health ser

-

vices (Rosenberg, Lu, Mueser, Jankowski, & Cournos, 2007), rates of childhood physical

abuse were much higher than those found in the National Comorbidity Study: 56.4%

abused versus 3.3% in the general population. Sexual abuse in childhood (33.6 versus

10.1%) was also elevated in the schizophrenia sample.

These rates are consistent with the larger set of studies looking at the combined

group of people with severe mental illness. These studies report almost universal (e.g.,

98%) exposure to any or all types of trauma over the lifetime. Although there are many

types of civilian trauma, the most common of which is the sudden, unexpected death of a

loved one, 87% of clients report more severe and less common traumas, including either

physical or sexual assault in childhood, in adulthood, or in both. Indeed, more than one-

third of clients living in the community report either physical or sexual assault in the last

year alone. By all accounts, being a person with schizophrenia or other severe mental ill

-

ness is generally a frightening and dangerous way to live, at least in the United States.

Often confined to low-income urban areas, likely to be intermittently homeless and incar

-

cerated, sometimes forced by circumstance into sex trading, and disproportionately likely

to abuse drugs in unsafe places such as crack houses, clients live in the most dangerous

spaces in a society where violence is rather common. In addition, it seems likely that these

clients’ common isolation and vulnerability make them likely targets of opportunity for

predators in such environments.

CORRELATES OF TRAUMA EXPOSURE

What happens to people following exposure to extreme, life-threatening events? For

many people, the hours and days following exposure are filled with anxiety, agitation,

and distress. Clients may feel emotionally numb, lose focus on the immediate environ-

ment, and feel as if they or events are “unreal” or “in a daze.” They may be unable to

stop thinking about the events, even though thinking about them is highly distressing.

People in the United States as a whole had at least an indirect experience of these symp

-

toms following 9/11, when, for example, people were horrified by the television footage

of the Twin Towers but could not help ruminating about the event. People found them

-

selves unable to concentrate on work or school. Some reported watching the news replays

over and over; others tried to avoid any news or mention of the attack. When these reac

-

tions become clinically significant and last for more than 2 days, they are called acute

stress disorder. For an unfortunately high percentage of trauma survivors, acute stress dis

-

order persists beyond 30 days, and progresses to PTSD. Other people exposed to trauma

may not meet criteria for acute stress disorder, but have instead delayed response to the

events and develop symptoms later. In either sequence, PTSD is the most common and di

-

rectly attributable psychiatric disorder to develop following trauma exposure, although

depression and substance use disorders may also ensue, with or without diagnosable

PTSD symptoms.

The steps by which PTSD develops after a trauma exposure have been well docu

-

mented. During and immediately following the event, the survivor experiences an intense

emotional response, including fear, anxiety, grief, helplessness, and often a complex mix

-

ture of all of these. Memories of the event are associated with reexperiencing all of these

emotions and, subsequently, elaborated emotions and ideas (e.g., guilt, sense of loss) as

the person continues to process the implications of the trauma. Because these recollec

-

tions are so emotionally charged and distressing, the person attempts to avoid memories

43. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Syndromes 451

or situations that are reminders of the trauma, which leads to further vigilance and

avoidant behavior. In addition, some traumatic events are so overwhelming that survi

-

vors’ assumptions about the world (e.g., “People are mostly OK”) and themselves (“I

know how to look out for danger as well as the next person”) can be shattered. They may

construct new cognitive frames or internal scripts that keep them locked in aspects of the

traumatic moment (e.g., “I could be attacked at any moment” or “No one can be

trusted”).

The severity of the trauma, the number of traumas to which persons have been ex

-

posed in their lifetime, the nature of available social supports, and the quality known as

psychological hardiness, or resilience, all influence the likelihood of developing PTSD fol

-

lowing exposure, as well as the severity and chronicity of this disorder. All these factors

seem to conspire to make people with schizophrenia highly vulnerable to developing

chronic PTSD.

Recent estimates of lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the general population range be

-

tween 8 and 12%, and the few available, community-based studies reporting point preva

-

lence of PTSD (the number of people who meet diagnostic criteria on any given day) sug

-

gest rates of approximately 2%: 2.7% for women and 1.2% for men. Studies of clients

with severe mental illness suggest much higher rates of PTSD. Seven studies have reported

current rates of PTSD ranging between 29 and 43% (Mueser, Rosenberg, Goodman, &

Trumbetta, 2002), yet PTSD, as discussed earlier, was rarely documented in clients’

charts. In the few studies with samples large enough to assess PTSD in clients by diagno-

sis, clients with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses had slightly lower rates (33%) than cli-

ents with mood disorders (45%), but rates in both groups were nevertheless much higher

than those in the general population. Another study reported that among persons hospi-

talized for a first episode of psychosis, 17% met criteria for current PTSD. This study, in

combination with the others, suggests that childhood trauma exposure and PTSD not

only occur more often in persons who develop schizophrenia and other forms of severe

mental illness, but that having severe mental illness also increases subsequent risk for

trauma and PTSD. As in the general population, PTSD severity in clients with severe

mental illness is related to severity of trauma exposure, and the high rates of PTSD in this

population are consistent with clients’ increased exposure to trauma. These rates also

suggest an elevated risk for developing PTSD given exposure to a traumatic event. For

example, in a sample of clients drawn from a large health maintenance organization,

Breslau, Davis, Andreski, and Peterson (1991) reported that the prevalence of PTSD

among those exposed to trauma was 24%. This rate of PTSD following trauma exposure

is approximately half the rate (47%) found in studies of trauma and PTSD in persons

with severe mental illness. The high PTSD rate in this population and its correlation with

worse functioning suggests that PTSD may interact with the course of co-occurring severe

mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and major mood disorders, worsening the out

-

come of both disorders. We developed a model to help us understand how trauma and

PTSD may interact with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses (see Figure 43.1).

TRAUMA, PTSD, AND THE COURSE OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

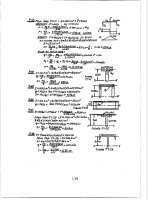

This model describes how PTSD directly and indirectly mediates the relationships among

trauma, more severe psychiatric symptoms, and greater utilization of acute care services

in clients with schizophrenia (Mueser et al., 2002). Specifically, we suggest that the symp

-

toms of PTSD may directly worsen the severity of schizophrenia due to clients’ avoidance

of trauma-related stimuli (resulting in social isolation), reexperiencing the trauma (resulting

452 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

in chronic stress), and hyperarousal (resulting in increased vulnerability to stress-induced

relapses). In addition, the model suggests that common clinical correlates of PTSD might

indirectly worsen schizophrenia, including increased substance abuse (leading to substance-

induced relapses), retraumatization (leading to stress-induced relapses), and poor working

alliance with case managers. It is important to treat PTSD in clients with schizophrenia to

reduce the suffering related to the disorder, and because PTSD may exacerbate the course

of schizophrenia, contributing to worse outcomes and greater utilization of costly ser-

vices through a number of mechanisms.

PTSD AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

PTSD is frequently chronic, often ebbs and wanes in intensity, and is characterized by

both clear biological changes and psychological symptoms. PTSD is also complicated by

the fact that it frequently occurs in conjunction with related disorders, such as depres

-

sion, substance abuse, problems of memory and cognition, and other physical and mental

health problems. The disorder is also associated with impairment of the person’s ability

to function in social or family life, including occupational instability, marital problems

and divorces, family discord, and difficulties in parenting. Given this cluster of primary

and secondary symptoms, it is readily apparent how some PTSD symptoms might be

overlooked in clients with schizophrenia, who frequently have problems in these life

spheres. Possible symptom overlap may lead to masking of PTSD in clients with a pri

-

mary psychotic disorder. For example, concentration and memory problems are common

in schizophrenia, as are restricted or blunted affect and sleep difficulties associated either

with the primary illness or with medication side effects. As with a client described earlier

in this chapter, PTSD may be expressed in psychotic terms, or in psychotic distortion of

actual traumatic events by clients with schizophrenia diagnoses. A client who was sexu

-

43. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Syndromes 453

FIGURE 43.1.

Heuristic model of how trauma and PTSD interact with schizophrenia to worsen the

course of illness. From Mueser, Rosenberg, Goodman, and Trumbetta (2002). Copyright 2002 by

Elsevier. Reprinted by permission.

Trauma

Substance

Abuse

Trauma

History

PTSD:

•

Reexperiencing trauma

•

Overarousal

•

Avoidance of trauma-

related stimuli

Symptom Severity,

Relapses, and Use of

Acute Care Services

Working

Alliance

Illness

Management

Services

ally abused in childhood might, for example, allude to this experience as being assaulted

by the devil, expressing both confusion about the event and the common desire of chil

-

dren to protect the actual perpetrator, who might even be a primary caretaker. Whatever

the sources of diagnostic ambiguity, including lack of provider awareness of trauma-

related disorders and lack of standardized screening for clients, multiple studies have now

reported that only about 5% of clients with severe mental illness and PTSD have the lat

-

ter diagnosis even listed in their charts, and almost none currently receive trauma-specific

treatment.

ASSESSMENT OF TRAUMA AND PTSD

Providers should be aware that there are simple, straightforward techniques for assessing

trauma history and PTSD in clients with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses.

Several studies, and much recent clinical experience, have now shown that clients respond

reliably and coherently to straightforward questions about trauma exposure (both early

and more recent), and can be assessed for PTSD symptoms with brief symptom invento

-

ries. These tests have been used successfully in paper-and-pencil format, as interviews,

and in computerized formats. They generally take about 10 minutes to complete. Despite

earlier concerns, these assessments rarely lead to increased distress (even in acutely ill cli-

ents), and are often appreciated by clients as indicators of provider concern about the is-

sues that really trouble them, yet have not been a focus of traditional mental health care.

One note of caution is worthy of mention: Providers who ask clients to participate in

these assessments, or who conduct them, may be uncomfortable themselves with some of

the topics covered (e.g., childhood sexual abuse or recent sexual assault experiences).

When this is the case, the providers may need some information and supervision on how

to conduct these assessments in a neutral, matter-of-fact, supportive way to ensure client

comfort and accurate, open reporting.

We have discussed how clients with both schizophrenia and PTSD may differ from

clients with schizophrenia alone. It is also important to observe that clients with both dis-

orders tend to present with many of the same issues as people with so-called “complex

PTSD,” as described by Herman (1992) and others. Complex PTSD has been observed in

people exposed to early or extreme stress, to neglect or abuse, and to multiple trauma ex

-

periences. In addition to the core symptoms of PTSD, which may be expressed in very in

-

tense form, complex PTSD involves dissociation, relationship difficulties, somatization,

revictimization, affect dysregulation, and disruptions in sense of self. Experts have argued

that people with complex PTSD are often diagnosed as having borderline personality dis

-

order, and this sometimes appears as a secondary diagnosis in clients with schizophrenia

who have extremely adverse life histories.

CURRENT TREATMENT APPROACHES

At this point in time, no published studies exist of treatment for clients with both

schizophrenia and posttraumatic stress syndromes. To our knowledge, none of the drug

trials for PTSD have included clients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders,

so we do not discuss pharmacological treatments in this chapter. Instead, we describe

several psychotherapeutic treatment models designed for the broader category of peo

-

ple with severe mental illness. The list is not comprehensive, but it is representative of

what is being developed, assessed, and implemented in the field. Developmental work

454 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

with these treatment models has included some (but not necessarily a majority) of cli

-

ents with schizophrenia. Assessment of the treatment models has involved either open

or randomized clinical trials of varying levels of rigor (e.g., uniform implementation;

good characterization of clients served; use of well-validated, standard outcome mea

-

sures).

Like trauma and PTSD treatments designed for the general population, these inter

-

ventions have relied on a relatively small set of therapeutic ingredients, often combining

with or employing somewhat different mixes and emphases. Common therapeutic ele

-

ments include psychoeducation, stress management techniques, teaching strategies and

resources to enhance personal safety, prolonged exposure to trauma-related stimuli (e.g.,

memories, safe but fear-eliciting situations), cognitive restructuring, group support, skills

training, and empowerment. Of these elements, the empirical literature on PTSD treat

-

ment in the general population has shown that prolonged exposure and cognitive restruc

-

turing are the most effective treatments. Interventions designed for more vulnerable pop

-

ulations, including those with psychotic disorders, have used both group and individual

formats (with some models combining the two), and intervention length has ranged from

12 weeks to 1 year or more. Some models have been developed specifically for women,

particularly women survivors of sexual abuse, whereas other, more general models are for

all types of trauma exposure (in either childhood or adulthood) leading to PTSD. Several

models focus on PTSD per se, whereas others attempt to address a broader array of prob-

lems associated with chronic victimization. These models, and the level of evidence sup-

porting them, are summarized in Table 43.1.

TREATMENT GUIDELINES

1. All clients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders should be assessed with stan-

dardized instruments for trauma exposure and for PTSD.

2. Providers working with these clients should be trained to understand post-

traumatic stress syndromes, and to recognize their symptom presentation in schizophre-

nia.

3. Services for such clients should be trauma-aware (e.g., housing recommendations;

gender of providers; guidelines for use of restraints for abused clients that factor in

trauma-related issues).

4. Clients should receive psychoeducation about trauma and posttraumatic stress

syndromes, including how to recognize PTSD symptoms, how PTSD might exacerbate

psychotic illness, and what treatments might be available.

5. Trauma-specific treatments (with different levels of empirical support) are avail

-

able and well described in the literature. Service systems that provide care for clients with

schizophrenia should choose trauma interventions best suited for their clients and set

-

tings, and train staff in providing these treatments.

6. Providers should learn who in their area is able to provide trauma-specific treat

-

ments for clients with both schizophrenia and PTSD symptoms.

7. Given the high level of ongoing trauma in clients with schizophrenia, periodic re

-

assessment for trauma exposure and PTSD should be part of standard care.

8. PTSD symptoms can persist over many years, and symptoms ebb and wane, often

in response to external stressors. Providers should be aware that clients’ PTSD may

reemerge, and follow-up treatments or “booster” sessions may be required when clients

undergo stress.

43. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Syndromes 455

456 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

TABLE 43.1. Treatment Approaches for PTSD and Other Posttraumatic Syndromes in Persons with

Schizophrenia and Other Severe Mental Illnesses

Intervention

name

(developer)

Target

population

Format

and length

Therapeutic

elements

Level of

evidence

Reference

Beyond Trauma

(Covington)

Women

abuse

survivors

Both group (11

sessions) and

individual

and group

(16–28 sessions)

Strengths-based

approach;

empowerment

oriented

Pre–post trial

under way

(150

participants)

Beyond Trauma

Manual

(S. Covington;

858-454-8528)

Seeking Safety

(Najavits)

Clients with

substance

abuse and

PTSD or

partial PTSD

25 topics

(variable

length);

group and

individual

Establish safety.

Teaches 80 safe

coping skills for

relationships,

substances, self-

harm, etc.

Several RCTs;

multiple open

trials (none

with identified

SMI clients)

Najavits (2002)

Target (Ford) Multiple-

trauma-

exposed

populations

Group and

individual

versions;

variable

length, 3–26

sessions

Strengths-based;

teaches symptom

monitoring and

self-regulatory

skills, experiential

exercises

Multiple open

trials (none for

SMI); one RCT

completed for

substance abuse

population

www.ptsdfreedo

m.org for

updates

Trauma

Recovery and

Empowerment

(TREM; Harris)

Women

trauma

survivors

Group

format, 24–33

sessions

Skills training,

psychoeducation,

peer support,

elements of CBT

Multiple open

trials, RCT

under way

(women with

SMI)

Harris (1998)

CBT for PTSD

among Public

Sector

Consumers

(Frueh)

People with

SMI and

PTSD

Group

(10–14) and

individual

(6–12)

sessions

Anxiety

management,

exposure, coping

and skills

enhancement

Treatment

development

phase (open trial

under way)

Frueh et al.

(2004)

CBT for PTSD

in SMI

(Mueser,

Rosenberg)

Clients with

SMI and

PTSD

Individual

(12–16)

sessions

Psychoeducation,

relaxation

One open trial

and one RCT

completed

Mueser et al.

(2004);

Rosenberg et al.

(2004)

Atrium (Miller

& Guidry)

Abuse

survivors

with related

problems

(substance

abuse, self-

injury,

violence,

severe

psychiatric

disorders)

12-session

individual,

group, or

peer-led

program

Psychoeducation,

relaxation,

mindfulness,

expressive

modalities,

elements of CBT

Participated in

multisite, open

trial (women

and violence

study)

www.dusty

miller.org

Syndrome-

Specific Group

Therapy for

Complex PTSD

(Shelley &

Munzenmeier)

People with

complex

PTSD and

SMI

12 sessions,

group

intervention

Psychoeducation,

skills training,

and social support

Pilot data only Syndrome-

Specific

Treatment

Program for

SMI Manual

(Vols. I–VI)

(shelleybpc

@aol.com)

Note. CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SMI, severe mental illness.

KEY POINTS

•

Trauma exposure is ubiquitous in clients with schizophrenia, as is PTSD, but trauma history

and posttraumatic syndromes are rarely assessed and treated in this population.

•

Trauma history and PTSD are associated with more severe symptoms (especially depres

-

sion, anxiety, and psychosis), worse functioning, and a more severe course of illness in cli

-

ents with schizophrenia.

•

Reliable and valid evaluations of trauma exposure and PTSD can be obtained in clients with

schizophrenia through the use of standardized assessment instruments, including inter

-

view, self-report, and computer-administered formats.

•

The assessment of traumatic experiences and PTSD in schizophrenia rarely leads to symp

-

tom exacerbations or other untoward clinical effects.

•

Treatment programs for trauma and PTSD in schizophrenia, based on effective interven

-

tions for posttraumatic syndromes in the general population, have recently been developed

and are being evaluated.

•

Preliminary experience with these treatment programs suggests that people with schizo

-

phrenia can be engaged and retained in treatment, and experience benefits from their par

-

ticipation.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READINGS

Blanchard, E. P., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T. C., & Forneris, C. A. (1996). Psychometric proper-

ties of the PTSD Checklist. Behavior Therapy, 34, 669–673.

Breslau, N., Davis, G. C., Andreski, P., & Peterson, E. (1991). Traumatic events and posttraumatic

stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 216–

222.

Cusack, K. J., Frueh, B. C., & Brady, K. T. (2004). Trauma history screening in a community mental

health center. Psychiatric Services, 55, 157–162.

Da Costa, J. M. (1871). On irritable heart: A clinical study of a form of functional cardiac disorder

and its consequences. American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 61, 17–52.

Frueh, B. C., Buckley,T.C., Cusack, K. J., Kimble, M.O.,Grubaugh, A. L., Turner, S. M., et al.(2004).

Cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among people with severe mental illness: A proposed

treatment model. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 10, 26–38.

Harris, M. (1998).Trauma Recovery and Empowerment: A clinician’s guide for working with women

in groups. New York: Free Press.

Harris, M., & Fallot, R. (Eds.). (2001). New directions for mental health services: Using trauma the

-

ory to design service systems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York:

Free Press.

Mueser, K. T., Bolton, E. E., Carty, P. C., Bradley, M. J., Ahlgren, K. F., DiStaso, D. R., et al. (2007).

The Trauma Recovery Group: A cognitive-behavioral program for PTSD in persons with severe

mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 43(3), 281–304.

Mueser, K. T., Rosenberg, S. D., Goodman, L. A., & Trumbetta, S. L. (2002). Trauma, PTSD, and the

course of schizophrenia: An interactive model. Schizophrenia Research, 53, 123–143.

Mueser, K. T., Rosenberg, S. D., Jankowski, M. K., Hamblen, J., & Descamps, M. (2004). A cogni

-

tive-behavioral treatment program for posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness.

American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 7, 107–146.

Mueser, K. T., Salyers,M. P., Rosenberg, S. D., Ford, J. D., Fox, L., & Carty, P. (2001). A psychometric

evaluation of trauma and PTSD assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psychological

Assessment, 13, 110–117.

Myers, A. B. R. (1870). On the etiology and prevalence of diseases of the heart among soldiers. Lon

-

don: Churchill.

43. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Syndromes 457

Najavits, L. M. (2002). Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New

York: Guilford Press.

Pratt, S. I., Rosenberg, S. D., Mueser, K. T., Brancato, J., Salyers, M. P., Jankowski, M. K., et al.

(2005). Evaluation of a PTSD psychoeducational program for psychiatric inpatients. Journal of

Mental Health, 14, 121–127.

Rosenberg, S. D., Lu, W., Mueser, K. T., Jankowski, M. K., & Cournos, F. (2007). Correlates of ad

-

verse childhood events in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services, 58,

245–253.

Rosenberg, S. D., Mueser, K. T., Friedman, M. J., Gorman, P. G., Drake, R. E., Vidaver, R. M., et al.

(2001). Developing effective treatments for post-traumatic disorders: A review and proposal.

Psychiatric Services, 52, 1453–1461.

Rosenberg, S. D., Mueser, K. T., Jankowski, M. K., Salyers, M. P., & Acker, K. (2004). Cognitive-be

-

havioral treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness: Results of a pilot

study. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 7, 171–186.

Salyers, M. P., Evans, L. J., Bond, G. R., & Meyer, P. S. (2004). Barriers to assessmentand treatment of

posttraumatic stress disorder and other trauma-related problems in people with severe mental

illness: Clinician perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal, 40, 17–31.

458 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

CHAPTER 44

MANAGEMENT OF

CO-OCCURRING SUBSTANCE

USE DISORDERS

DAVID J. KAVANAGH

NATURE OF THE ISSUES IN COMORBID POPULATIONS

In recent years there has been increasing interest in effective ways to manage people with

both psychoses and co-occurring substance use disorders (SUDs). Despite the importance

of these problems, treatment research in this area remains at a relatively early stage, with

few well-controlled trials and outcomes that are often quite weak. However, we now

have a substantial body of research on the nature, incidence, and correlates of SUDs in

psychoses, and on the nature and perceived limitations of existing services. This research

has clear implications for interventions.

SUDs Are Very Frequent in People with Psychoses

About half of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders have an SUD at some time in

their lives. In treatment settings, rates can be even higher—especially in acute or crisis ser

-

vices, or in services for people with high needs for ongoing support, because the combina

-

tion of problems increases problem severity and risk of relapse.

There are important implications for clinical practice that arise from this observa

-

tion. First, because comorbidity is so common, screening for substance use should be uni

-

versal and routine in initial assessments and status reviews of people with psychosis. Sec

-

ond, routinely offering more intensive or prolonged treatment than that available at

present to everyone with schizophrenia and an SUD would have substantial resource

implications. Unless budgets and staffing receive a substantial boost, or other consumers

receive less intervention, there will be severe limitations on the extent to which such addi

-

tional treatment can be contemplated. Exporting the problem to another service (e.g., an

alcohol and other drug service) just shifts rather than solves the resource problem.

459

Three potential strategies present themselves. One would be to embed most treat

-

ment for comorbidity within standard treatment sessions. A second would ensure that all

affected patients received at least a brief intervention. A third would restrict substantial

amounts of additional treatment to the patients most likely to benefit from it. This chap

-

ter takes the view that a combination of all three ideas should be considered (Table 44.1).

Risk Factors and Selected Substances Are Similar to the Rest

of the Population

Rates of co-occurring SUDs typically follow community patterns, so that young people

and men are at increased relative risk, as are people from groups with higher consump

-

tion (e.g., single or divorced people, the unemployed, members of alienated indigenous

communities or of cultural groups with heavy substance use). Substance use is also more

common in time periods or in geographical areas where substances are readily obtained

at low cost.

The substances selected by people with psychoses also follow the pattern in the gen

-

eral community. Typically, surveys in Western countries over the last 20 years have found

that the recreational drugs most commonly used by people with psychoses (other than

caffeine) are nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis, usually in that order. However, drug selec

-

tion can vary dramatically across time and locality, with changes in production, law en-

forcement, and fashion or acceptance. In the last 10 years, amphetamine, cocaine, and

heroin consumption have each demonstrated this phenomenon. There is also evidence

that the pattern of demographic correlates may differ across particular drugs—for exam-

ple, that age may be a weaker predictor for alcohol than for cannabis, because alcohol

has been less subject to cohort effects over the last 50 years. The predominant drug and

the demographic correlates can also vary across treatment services, according to local

characteristics and the nature of the service.

Together, these observations suggest that we need to design and offer treatments that

are appropriate for high-volume groups, such as young men, and for the substances cur-

rently in most common use. At the same time, the needs of other groups (e.g., women,

older people, users of less common drugs) should not be ignored.

SUDs Have a Substantial Impact on People with Psychoses

The high frequency of comorbidity would not be such a major issue if it did not have sub

-

stantial impact. Unfortunately, comorbidity has severe individual and collective effects

that encompass patients, their families and friends, a wide range of health and social ser

-

vices, and the community at large. SUDs contribute to costs by exacerbating symptoms,

producing functional deficits and triggering impulsive behaviors (including self-harm, ag

-

gression, and high-risk sexual activity). The impact is not just financial, as large as that is;

it also includes emotional and psychological impacts, and both objective and subjective

quality of life. Mental health services are not immune to the increased costs. Untreated,

this group is overrepresented by those who repeatedly relapse or have chronic, severe

functional deficits. They are particularly common in users of high-cost services, such as

crisis and emergency care, high-support community housing, and inpatient facilities. Un

-

less service capacity is high, this means that other consumers miss out on the level of ser

-

vices they need. Despite the difficulties in addressing comorbidity in a proactive fashion,

there is an imperative to do so.

The complexity of comorbid problems is usually compounded by multiple substance

use. An obvious implication is that treatment focusing on only one drug may have limited

460 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

impact or leave people at risk of relapse, if it ignores potential relationships with other

substances. Examples are people’s difficulties resisting consumption when intoxicated

with another drug; ongoing contact with suppliers, users, or usage contexts for other

drugs; use of the same mode of administration, such as smoking or injection for multiple

drugs; and strategic consumption to deal with effects of other drugs. Both clients and

treatments may productively target one substance at a particular time, but this focus

should not become myopic and miss cross-substance influences.

The high levels of service contact and poor response to previous treatment com

-

monly seen in this group lead many therapeutic staff to be doubtful of success or to lack

self-efficacy about being able to provide effective treatment. It is important to remind

ourselves that recovery from a substance-related problem often requires several attempts,

44. Management of Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders 461

TABLE 44.1. Treatment Recommendations on Co-Occurring Mental Disorders and SUDs

Recommendations from epidemiological research

1. Universally screen for SUDs in people with psychosis.

2. To maximize access and restrict cost:

•

Integrate comorbidity work in standard treatment.

•

Routinely apply brief interventions.

•

Restrict high-cost interventions to those who will benefit only from those treatments.

3. Have treatments that are suitable for the following, while ensuring that less common groups are

also addressed:

•

High-risk groups (e.g., young men).

•

Substances currently in common use among the service’s consumers (e.g., nicotine, alcohol,

cannabis, cocaine/amphetamines).

•

Use of multiple substances.

4. Ensure that treatments can deal with initial instability in substance control, and that optimism

about recovery is expressed. Even in low-intensity treatments, some ongoing, assertive contact

may be required.

5. Intervene early to help preserve prospects of functional recovery.

6. Present comorbidity interventions in the context of maintaining optimal physical and mental

health to reduce stigma and maximize engagement. Nicotine smoking should be an important

focus.

7. Any problematic responses by others should be addressed (e.g., in family intervention) and

highly confrontational approaches to clients should be avoided.

8. Any responses by the service to substance-related infractions should be proportional and

expected, and minimize threats to engagement or relapse.

9. Treatments should offer more opportunities for pleasure and mood enhancement than are taken

away.

10. Treatments for complex problems should sequentially focus on the single behavioral change with

the greatest potential impact on the current problems.

Recommendations based on treatment outcome research

1. Mental health and SUD treatments for people with serious mental disorders should be fully

integrated and routinely offered by the mental health service, with consultative support from

alcohol or other drug services where required.

2. People with serious mental disorders and severe substance dependence may require input from

multiple services.

3. Current trials do not offer strong support for any specific treatment component or set of

components. Approaches used with each disorder have some effect.

4. A staged approach to treatment intensity should be considered, with higher intensity treatments

reserved for consumers who do not respond to lower intensity treatments.

and that we have sometimes found it hard to maintain attempts to change our own be

-

haviors in the past. People with comorbid mental health problems may find it particularly

difficult to initiate and maintain behavior change, especially if they have deficits in prob

-

lem solving or prospective memory, experience severe negative symptoms, or are depressed—

as so many are. If their practitioners do not model persistence and optimism, it is difficult

for consumers to maintain optimism and persistence themselves.

There is an upside. Although SUDs have a very negative impact on outcomes, people

who develop a co-occurring SUD often have levels of premorbid functioning that are as

good as or better than those of patients without an SUD. One possible reason for this ob

-

servation is that people with higher premorbid social functioning may be at greater risk

of exposure to substance use. To the extent that premorbid abilities are preserved, treat

-

ing the SUD may offer a relatively good prognosis. This effect is most evident in consum

-

ers whose psychosis is truly secondary to their substance use, and who typically recover

rapidly once they stop consuming the drugs, but it may also be true of persons with truly

independent disorders. There may, however, be some urgency in addressing the problem

before it is too late. Use of cannabis and other substances triggers an earlier average tra

-

jectory of psychosis, interfering with both education and social development, and with

the final stages of brain maturation. It is imperative that we help consumers address

SUDs and maximize their potential, before windows of opportunity for socialization and

career development are lost. Ideally, we need to prevent the brain insult that underlies the

first episode of psychosis. If we cannot do that, we need to try to ensure that consumers’

initial episode is also their last, and that their ultimate functioning is maximized.

Small Amounts of Drugs Can Have Large Effects

As a group, people with psychosis and an SUD are very different from the majority of

people in the general population who request treatment for SUDs. On average their con-

sumption is lower, and they are less likely to show a severe substance dependence syn-

drome. This is partly because they can rarely afford large amounts, and partly because

many people with severe mental disorders are exquisitely vulnerable to negative impacts

from small quantities of drugs. The vulnerability does not extend only to symptoms and

interactions with prescribed drugs. Because this population usually already has significant

functional deficits, these individuals are very susceptible to additional impact. Given that

most have a very low income, smoking and other substance use have an early effect on

other spending, in many cases, affecting not only discretionary spending (e.g., movies,

outings, or small indulgences) and narrowing sources of pleasure but also impacting es

-

sential purchases, such as food, clothing, and shelter.

The same amount of a drug may have very different effects on the same person, de

-

pending on the situation at the time. So, a person within a more vulnerable period for

psychotic symptoms, or with temporarily less disposable money, may have more negative

effects than usual. There is also substantial individual variation. In some people, any use

of particular substances creates havoc for their mental state and functioning. This can be

difficult for consumers to acknowledge if they are using considerably less of the drugs

than their peers. As in other addiction contexts, highly vulnerable consumers often adopt

an initial goal of harm reduction or moderation before they appreciate that abstinence of

-

fers the best outcome. Respecting their decision and assisting them in the attempt does

not imply agreement that the goal is appropriate; it acknowledges their positive motiva

-

tion and maintains an alliance that can ultimately result in more complete success.

Not all effects of substances are direct. Some problems arise from negative responses

of other people. Intoxication is more salient in people who are displaying odd behavior. It

462 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

is also tempting for friends and relatives to blame substance users with serious mental

disorders for their own symptoms. These reactions substantially increase the risk of sub

-

sequent psychotic relapse. In fact, this indirect influence can sometimes be stronger than

direct effects of the drug. Exclusion and rejection are seen in a number of contexts, unfor

-

tunately, including health services and assisted accommodation. Effects of such exclusion

can be catastrophic.

There are at least two implications for treatment. First, interventions assisting fami

-

lies and friends to cope with the person’s co-occurring psychosis and SUD may be very

important. Second, we should ensure that our reactions to these people do not worsen

their prognosis or lead to their permanent exclusion. Although there are good reasons to

ban substance use within specific contexts (e.g., on treatment or accommodation sites, or

before sessions), avenues for support and treatment of those who do use must remain

open. Any consequences should be proportional, temporary, demonstrably fair (e.g., ab

-

breviation and rescheduling of the session), and protective of the health and welfare of all

parties. It is no more appropriate to exclude lapsing substance users from service than to

exclude people with symptomatic exacerbation from appropriate service responses.

The large impact that typically follows relatively low consumption of recreational

drugs means that the majority of people with serious mental disorder and an SUD who

are seen in most mental health services do not show high levels of physical dependence or

need assisted withdrawal. This is not to say that attention to physical risk is unimportant:

Both the psychosis and the substance use increase the risk of physical exposure, impaired

self-care, injury, and infection (including infection with HIV). Self-harm, suicide, and ei-

ther committing assault or being the victim of it are more likely in people with an SUD

than in those without an SUD, and assessment of these risks is essential. Given the height-

ened risk of serious physical disorder in this population, and the risk of misdiagnosis or

inadequate treatment, mental health and SUD services have an obligation to provide rele-

vant consultation and training to ensure that general medical staff are able to meet the

significant challenges this population may pose. Services are also needed for people with

both a severe mental disorder and severe substance dependence, who often need a high

level of ongoing treatment and support, and input from a range of specialist services.

Often There Is Little Else in the User’s Life

Substance use in people with psychosis is usually in the context of a very impoverished

existence, with drug users constituting their primary or only friends, and with few alter

-

native recreational activities. These individuals rarely use substances to address psychotic

symptoms, but they often cite relief of dysphoria or boredom as key reasons for con

-

sumption. Corollaries are that motivation enhancement and relief of dysphoria may be

important components of successful treatment. Because dysphoria lowers self-efficacy,

strategies that boost confidence and address responses to perceived failures may often be

required. Interventions need to provide more social advantages and opportunities for

mood enhancement than they take away.

This Group Usually Has Complex, Intertwined Issues

The term dual diagnosis comes nowhere near an accurate description of the complexity of

problems typically seen in this population. Most people with psychosis and co-occurring

SUD use more than one substance, and many have additional mental health problems

(e.g., depression, social anxiety, and personality disorders). As already noted, often they

44. Management of Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders 463

also have physical disorders and a complex web of social, financial, legal, housing, and

occupational issues. It is time that we recognize this complexity by using a different term.

Significant practical issues are raised by this complexity. Which problem should be

addressed first? Which ones are critical to overall recovery?

In some cases, the mental disorder may be secondary to the substance use, and treat

-

ing the latter can resolve the former. However, this is not strictly a group with independ

-

ent, co-occurring disorders. For most people with both psychosis and an SUD, the prob

-

lems are linked by threads of mutual influence. For example, symptom exacerbation is

more likely after greater cannabis use, but higher cannabis use is also more likely when

symptoms are worse.

A more complex or multifaceted treatment is not necessarily the answer—especially

if treatment strategies simultaneously impose high memory or performance demands on

participants. Focusing on one current treatment target that is likely to produce the most

impact on the total set of problems may be a better approach. An example of a potential

target with multiple impacts is increasing positive, nondrug activities: This potentially

affects not only the time spent on substance use and total amount consumed but also ad

-

dresses dysphoria and perhaps social contact. Another example, employment, offers mul

-

tiple opportunities for pleasure and increased functioning, provides a strong reason for

substance control, and is inconsistent with substance use over most of the week. Multi-

impact treatment targets need to be identified for each individual and tailored to his or

her current status and valued goals.

Priority Setting Requires a Balance of Frequency, Severity,

and Acceptability

The most commonly used drugs are not necessarily the ones with greatest impact on psy-

chotic symptoms, physical health, or social functioning. Injected or smoked drugs and

illegal drugs of unknown content or potency, of course, pose particular risks. Hallucino-

gens and amphetamines have particularly strong effects on symptoms, as can cannabis,

but as I already noted, nicotine and alcohol are by far the most commonly used sub-

stances. As a result, the latter drugs have the greatest impact in the population with

severe mental disorders, just as they do in the general population. There are sometimes

difficult priority issues relative to substances: Should we focus on the substances that most

commonly affect clients, or on those that have the greatest impact on individual users?

Clearly, there is not a single answer to this question, but initial work with individual

clients is usually more productive if it focuses on substances about which they are already

concerned. One substance that scores high on both frequency and risk is also a common

focus of client concern. Nicotine is not only the most common substance used by people

with psychoses (up to 80% smoke cigarettes according to surveys) but it is also the great

-

est single contributor after suicide to excess mortality and morbidity in psychosis. Nico

-

tine use is often neglected as a treatment target—perhaps because of high rates of smok

-

ing by staff, because of its use in the past to calm or reward clients, or because there is

little evidence that it exacerbates psychotic symptoms. In fact, nicotine moderates nega

-

tive symptoms, improving cognitive performance in particular. However, the additional

dopamine release and faster drug metabolism seen in smokers mean that up to 50% more

of the older antipsychotics is needed for effective symptom control. Cigarette smoking is

a noncontentious target for many consumers, because of exposure to public campaigns

on the dangers of smoking, and because it is not subject to the same opprobrium as illegal

substance use. Nicotine should not be neglected in assessment and intervention for

comorbidity.

464 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

DESCRIPTION OF TREATMENT APPROACHES,

AND EVIDENCE FOR THEM

There are three main approaches to multiple disorders. One is to address them sequen

-

tially. This may be especially useful when clearly there is one primary problem, and other

problems simply flow from it. A second approach is to treat the disorders in parallel. This

implies that they are independent disorders that co-occur by chance, and also that treat

-

ments for the disorders will not interfere with each other. A third approach is integrated

treatment for both disorders by a single treatment agent. Each aspect of the treatment

takes the full set of issues into account and is tailored to have maximum impact on multi

-

ple areas. A single, coherent treatment plan attempts to address the disorders and the as

-

sociations between them. This does not, of course, require that all treatment components

are applied simultaneously—just that all elements take account of the total context.

A body of research has attempted to determine which of these models is best for peo

-

ple with psychosis and SUDs. Although there are few randomized controlled trials and

significant methodological limitations to the current research, the current evidence is

more in favor of an integrated treatment by a single agent than treatment with other

models. There are several possible reasons for this observation: Integrated treatment, by

definition, ensures some treatment for both conditions, and communication is ensured.

There is more likely to be consistency in advice and objectives, and each aspect is more

likely to be tailored and timed to take into account other comorbid conditions. Consis-

tency is also present in the therapeutic relationship. Each of these features could conceiv-

ably be obtained in a model involving more than one treatment agent, and with parallel

or sequential aspects, but it would be much more difficult.

In many countries, services for mental health problems and SUDs are offered by sep-

arate agencies, with a very different mix of professional backgrounds, inclusion criteria,

treatment foci and objectives, methods, and degree of assertive follow-up. Frequently

they are in separate locations, and intersectoral communication is often problematic.

Gaps are commonly reported in perceived ability to manage problems that are seen as the

province of the companion sector. These structural features create significant difficulties

for individuals with multiple, complex problems. Historically, often they have been ex

-

cluded from one or both services altogether, or left to negotiate treatments with multiple

agencies themselves. This has sometimes meant that only the most motivated and re

-

sourceful consumers and families have been able to obtain an acceptable standard of

treatment for comorbidity. Sequential treatments often become sequential culs-de-sac;

parallel treatments may take diverging or conflicting paths, and integrated treatment may

be extremely difficult if not impossible.

How then do we resolve this problem? Even if services are combined, attitudes, prac

-

tices and professional specialities may still carry over. Should specialist comorbidity

teams be established? Such teams can be very useful in promoting cross-sectoral training

and offering supervision or specialist consultation, but a risk is that other staff members

may attempt to slough off all relevant consumers to that team, so that it is soon over

-

whelmed by the caseload. A set of service criteria and priorities would inevitably have to

be established, and there would be a new basis for service exclusion.

There is a practical alternative. If the regular treatment staff from each service takes

responsibility for the assessment and management of the kinds of comorbidity that rou

-

tinely present in its service, an integrated model of treatment can be delivered. Consumers

with serious mental disorders could be assured of treatment by the mental health service

for a comorbid SUD. Conversely, individuals presenting to a specialist SUD service could

expect to have comorbid anxiety or depression treated. Some services already run on this

44. Management of Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders 465

model, although some others remain stuck in a less flexible or encompassing role. A cor

-

ollary of the recommended approach is that staff members acquire competence in manag

-

ing the commonly presenting comorbidities in their service, and that quality control and

accreditation encompass management of comorbidity as a core function. Comanagement

of comorbid disorders across services, or management by specialist comorbidity trainers

or consultants, could then be limited to individuals with particularly severe or apparently

intractable problems.

EVIDENCE ON TREATMENT EFFECTS

Current evidence suggests that some atypical antipsychotic medications may reduce other

substance use, and that most medications for substance misuse may (with some provisos)

be safely applied in people with serious mental disorders. However, there are few data as

yet on the specific efficacy of the latter drugs for people with psychosis.

There are still very few randomized controlled trials on psychological interventions

for comorbidity in the literature. They often obtain relatively weak, short-lived, or patchy

results across different substances, and many positive results are not subsequently repli

-

cated. This is the case even when the intervention is much more substantial and intensive

than would be practical in a standard service. On the one hand, in common with the gen-

eral literature on the treatment of SUDs, initial changes by individual participants are

often unstable, and multiple attempts at control are often needed. Extended treatment

may often be required.

On the other hand, evidence on interventions for risky alcohol consumption in the

general population suggests that opportunistic brief interventions can be remarkably ef-

fective. These interventions typically involve feedback of results from screening and as-

sessment, and advice to stop or reduce substance use, sometimes with specific suggestions

on how to do it. The number and duration of treatment sessions differ widely, but single-

session interventions of 5 minutes or less still have significantly better effects than no

treatment, and brief interventions give the same average impact as longer ones.

Motivation enhancement,ormotivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), is

a style of intervention that can be used in either a brief format or as the precursor to lon

-

ger treatment. It encourages clients to express ambivalence about their current substance

use, and how it fits with their self-concept and goals. There is no attempt to persuade or

argue with clients—instead, they are encouraged to develop awareness of their own moti

-

vations for change. Both brief interventions in general and motivation enhancement have

particularly strong supportive evidence for change in alcohol consumption (Miller &

Wilbourne, 2002), but they have also been applied to other behavior targets.

There is some evidence that motivation enhancement can be effectively adapted to

comorbid populations, generating engagement in subsequent extended treatment, and

serving as a relatively brief, stand-alone intervention. However, as in the case of longer

treatments, evidence on substance-related changes is inconsistent. At least some of the

difficulty that is experienced in controlled trials may reflect the fact that some clients suc

-

cessfully make significant and sustained changes in their substance use after having an in

-

patient admission, with little or no specific intervention. Perhaps their reaction to an ad

-

mission and their awareness (whether preexisting, or triggered by staff comments) that

substances may have triggered it is as much intervention as this group needs. Or it may be

just a matter of regression to the mean: Their substance use before admission was more

than usual, triggering an episode, but they then returned to more usual consumption. We

need to find out more about natural recovery processes in this population to understand

how we can increase the proportion of people who fall into this group.

466 VI. SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND PROBLEMS

Up to now, there has been little success in a priori identification of consumers who

will benefit from brief comorbidity interventions. Those with less severe or less chronic

problems, for example, do not necessarily show better outcomes. This observation, to

-

gether with cost considerations, suggests that a staged model of intervention may be indi

-

cated, in which all affected consumers receive a brief intervention, with some repetition in

individuals with fragile motivation. Motivated consumers who have difficulty maintain

-

ing an attempt may need additional support and targeted skills training, or adjunctive

pharmacotherapy. A small group that is at acute physical and psychiatric risk and is un

-

able to respond to skills training may need more intensive environmental support (e.g.,

supervised living environments). Such a staged approach to treatment delivery would

need to ensure that consumers not see stage progression as a reflection of their own fail

-

ure (perhaps by drawing an analogy to particular medications being more effective with

some people than others).

GUIDELINES FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL TREATMENT

Where does this leave us as practitioners? Given the current state of the evidence, any rec

-

ommendations must be tentative. When the epidemiological and treatment outcome re

-

search are considered, some specific guidance is given. Table 44.1 summarizes the impli-

cations for treatment relative to the issues already discussed in preceding sections. But

what components of psychological intervention should be considered?

Development of Rapport

It is critical that clients trust that the information they divulge will not result in negative

outcomes (exclusion from service, legal consequences, or disapproval); otherwise, they

will withhold information about substance use (and other potentially sensitive issues).

One the one hand, at least “denial” of problems may also be more accurately described

as nondisclosure. On the other hand, provided that rapport and trust are well established,

reports of consumption can be as accurate as assays (or more so, if a report extends

beyond the detection period of the assay). Trust is established by the therapist demon

-

strating empathy and positive regard in response to other personal information, and by

providing specific reassurance about lack of consequences for disclosure. General conver

-

sations about the person’s interests, usual activities, and goals are especially useful in later

motivational interviewing.

Brief Intervention or Advice

If there is insufficient opportunity for anything more, people with comorbidity should be

provided nonjudgmental feedback on outcomes of screening and assessment. Brief advice

from an expert may be persuasive in some cases, particularly if the person is already con

-

cerned about the issue. However, highly confrontational interactions should be avoided

in this population, because of their potentially detrimental symptomatic impact. Further

-

more, some people are likely to react defensively to direct suggestions about either their

substance use or concurrent mental disorder. Motivational interviewing (Miller &

Rollnick, 2002) minimizes defensive reactions and often elicits motivation for change,

even when the person was not initially contemplating it. Adjustments for people with se

-

rious mental disorder may include splitting the process into several short sessions, revis

-

ing the process on each occasion, and including more summaries than usual. We have

found that the approach can even be used during a psychotic episode, as long as clients

44. Management of Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders 467

are not acutely distressed, and can maintain attention to a single topic of conversation

over a 5- to 10-minute period (with prompting, if necessary).

Planning behavior change should initially focus on preparations that specify when

and how action will occur, and strategies to support the person through the initial days.

Potential challenges in the first 7 days are identified, and ideas on how to address them

are generated, rehearsed, and practiced. Our version of this intervention (Start Over and

Survive [SOS]) totals 3 hours, including rapport development, motivational interviewing,

and planning, and leaves participants with a series of pocket-sized personalized leaflets to

remind them about their own situations and plans. In the case of participants who are liv

-

ing at home, we also deliver a single session to relatives, to generate empathy and encour

-

age their continued support, while setting appropriate limits. If there is a delay in ap

-

pointing case managers after discharge, we make brief, weekly telephone calls to clients

over the first month to acknowledge progress, to review their reasons for change, and to

cue problem solving.

Our research group uses individual sessions, because this provides maximum flexi

-

bility in delivering coherent, integrated, and individualized treatment over the course of

short inpatient stays (often 3–5 days), when consumers are acutely psychotic and thought

disordered. Within longer admissions or ongoing outpatient contact, group sessions may

be used to consolidate motivation and to model success. Obviously, care needs to be

taken that negative modeling, supplying drugs to other members, and conflict are

avoided.

Skills Training and Ongoing Group Support

Some clients need training in problem solving, substance refusal, management of

dysphoria, medication adherence, or other specific skills, before they are on track for re-

covery. Many also need ongoing encouragement, reengagement after lapses or symptom

exacerbations, or additional support when external stressors or dysphoria are higher than

usual. Development of pleasant activities, social relationships, and social roles that are