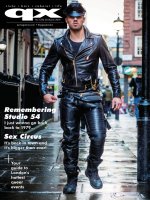

IT training new york magazine TruePDF 18 march 2019

Bạn đang xem bản rút gọn của tài liệu. Xem và tải ngay bản đầy đủ của tài liệu tại đây (36.07 MB, 96 trang )

TV. Streaming. On Demand.

y Rebecca

raister

p.16

Terry Gilliam / Ta-Nehisi Coates / Paul Cadmus / Pluss: Donald Trump’s Speed Dial

March 18–31, 2019

®

the

as

b

lain

e d.

s

to

.

exp

g

ng

ts

ni

d

w

od p

pe

ak

ed

it

s

a

u s :H

dy

a

e

lr

6

0,

Also:

Learn to exercise

your ear, and

other teeny-tiny

workouts.

p.47

m

?

he

By

g

ea

ur

n

i

t

e

for

yo

ere

ST

E

B

N

R

m nd A

a

K

s

i

r

Bo

a

d

A

atr’s

te

nt

io

n.

G

R

E

K

CH

H

A

0

0

1 rth

lis

the

te

po

s

ca

wo

march 18–31, 2019

features

M A K E U P BY PA U L E T T E CO O P E R

Stacey Abrams, ____?

She isn’t the governor of

Georgia. So what should she

do next? Abrams is conflicted.

By Rebecca Traister

16

The Great Pod Rush

Has Only Just Begun

But now that Big Money has

its grubby hands on it, will

podcasting ever be the same?

By Adam Sternbergh

and Boris Kachka

22

AACK!

Cathy Guisewite broke through

the glass ceiling by creating

a character for whom

disempowerment was a way

of life. She’s still facing

down that paradox today.

By Rachel Syme

36

Stacey Abrams

Photograph by Dan Winters

3

intelligencer

the culture pages

9

65

What the president’s

compulsive phone

habits say about him

By Olivia Nuzzi

12

100-Person Poll

Strangers on the

street tell us how the

presidency will end

14

Politics

Ta-Nehisi Coates on

race relations and the

Dems in the Trump era

By Eric Levitz

the cut

40

Report From

the Shows

Goth boots, RBG,

primary-color pantsuits, and Cathy Horyn

on Karl’s swan song

strategist

47

Best Bets

Rocking chairs for a

younger crowd; a store

designed for big boobs

49

Look Book

The Parsons student

who summers

at a larping camp

50

Micro-Workouts

Forget abs and

quads—show

your ears and toes

some love

By Katy Schneider

and Simone Kitchens

56

Food

What to eat at Hudson

Yards; Platt on Rocco

DiSpirito’s second act;

elevated hot pockets

6 Comments

90 New York

C

b

ey

92 The Approval

Matrix

4 n e w y o r k | nymag.com

march 18–31, 2019

The Man Who

Was Almost Killed

by ‘Don Quixote’

Terry Gilliam’s 30

years spent tilting

at windmills

By Bilge Ebiri

70

The Painting Our

Art Critic Can’t Stop

Thinking About

Paul Cadmus’s atlas

of American violence

By Jerry Saltz

72

Lady Killer

Jodie Comer plays

the kind of assassin

you might like

to go shopping with

By Allison P. Davis

74

The Hunter

Becomes the

Hunted

A former critic,

and co-creator

of Beetlejuice

on Broadway, can’t

shake the fear

By Scott Brown

76

Critics

movies by David

Edelstein With Us,

Jordan Peele’s horror

syntax keeps growing

theater by Sara

Holdren Be More

Chill does high

school with knowing

wickedness

tv by Matt Zoller

Seitz Kingdom

is resonant

and disturbing

80

To Do

Twenty-five

picks for the next

two weeks

on the cover:

Photograph by

Bobby Doherty for

New York Magazine.

this page:

Terry Gilliam.

Photograph by Jim

Naughten for

New York Magazine.

For customer service, call 800-678-0900.

O N T H E CO V E R : M A K E U P B Y R O B E R T R E Y E S F O R M A M - N YC

The Swamp

BLAZE NEW

TRAILS

INTRODUCING THE

FIRST-EVER LEXUS UX

We no longer travel great distances in the name of

exploration. Today, our frontier is all around us. For those

seeking this new frontier, the first-ever Lexus UX is a

new frontier for crossovers. Crafted purposefully for the

city. To nimbly handle corners with a best-in-class 17.1-ft

turning radius.1 To easily navigate cluttered roads with

Apple CarPlay®2 while connected to your iPhone.®3 And to

inspire a sense of freedom with a class-leading estimated

33 MPG.1,4 Introducing the Lexus UX and UX Hybrid

AWD,5 both available as F SPORT models. Crafted for

those who believe there is always something new to explore.

lexus.com/UX | #LexusUX

UX 200

Options shown. 1. 2019 UX vs. 2018/2019 competitors. Information from manufacturers’ websites as of 9/17/2018. 2. Apple CarPlay is a trademark of Apple Inc. All rights reserved. Always drive safely

and obey traffic laws. Apps, prices and services vary by phone carrier and are subject to change at any time without notice. Subject to smartphone connectivity and capability. Data charges may apply.

Apple CarPlay® functionality requires a compatible iPhone® tethered with an approved data cable into the USB media port. 3. iPhone is a registered trademark of Apple Inc. All rights reserved. 4. 2019

Lexus UX 200 EPA 29/city, 37/hwy, 33/comb MPG estimates. Actual mileage will vary. 5. UX AWD system operates at speeds up to 43 mph. ©2018 Lexus

Comments

PETER

BOGDANOVICH

IN CONVERSATION

The director on his films,

marriage and

infidelity, and the deaths

he didn’t mourn

By

ANDREW GOLDMAN

46 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 4 1 7 2 0 1 9

In New York’s latest issue, Simon van

Zuylen-Wood asked, “When Did

Everyone Become a Socialist?” (March

4–17). Susan Simon responded, “The

answer to your cover question … resides on

the cover of your [Hudson Yards] issue,”

which featured stories that portrayed the

new development as a gilded community

for the one percent. Of the socialism feature,

Armin Rosen wrote, “Man, this is good.

Really illustrates the weirdness of environments where everyone more or less thinks

the same.” Others took exception to the

focus of the story, which opened at a party.

Maya Kosoff tweeted, “A more honest and

incisive and less decadent story would have

been one about organizers in New York and

not media people at a party.” Emily Cameron

wrote, “The stereotypes of ‘the nearly allCaucasian DSA left’ depicted in this piece

give the wrong view of socialism. As a

25-year-old queer Latina and co-chair of

DSA Fresno in California’s rural Central

Valley, I can assure you that the DSA I know

1

is not a circus of ‘white, 21-to-36-year-old

Tecate drinkers’ on dating apps, listening

to podcasts, obsessed with BernieSanders.

I wish DSA chapters outside the media

bubble got attention. DSA is growing pre-

cisely because the left as a whole is growing.

The American left is complex, diverse, and

beautiful. That’s why we’re winning.” In the

story, van Zuylen-Wood explains that when

social theorist Michael Harrington founded

DSA in 1982, the “group occupied the ‘left

wing of the possible,’ a sensible enough

mantra that excited nobody and helped the

organization stay minuscule for decades.”

Harrington’s biographer and DSA charter

member Maurice Isserman, challenged

that assessment: “Harrington’s DSA was

6 new york | march 18–31, 2019

peter bogdanovich is often held up as a cautionary ta e of Holly

wood arrogance, Icarus with big frames and a nec

ief In a hurry

since adolescence, at 16 he talked his way into a

g classes with

Stella A ler; at 20, he persuaded C ifford Odets to him direct one

of his p ays Off Broadway; and he went on to b end and write

about the golden age movie directors he idolized, like Orson Welles,

John Ford, and William Wyler As soon as Bogdanovich became a

director in his own right, his

assurance didn t endear him to

some of the towns young aute

old egends I don t judge myself

on the basis of my contempo

s, he told the New York Times

in 1971 I judge myself against the directors I admire Hawks,

Lubitsch, Buster Keaton, Welles, Ford, Renoir, Hitchcock I cer

tain y don t think I m anywhere near as good as they are, but I think

I m pretty good And so, as the story goes, Bogdanovich directed two

arguab y perfect films, The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon, along

with the h t screwball comedy What s Up, Doc?, only to see his career

run aground after a ser es of flops But contrary to the legend, Bog

danovich never disappeared or stewed in defeat for long, and he as

enjoyed no fewer than three critical y hailed comebacks with Saint

Jack (1979), Mask (1985), and Cat s Meow (2002), as well as signifi

cant late career success as a documentarian, as with 2007 s Tom

Petty documentary, R nnin Down a Dream Bogdanovich has also

shown himself to be a surprisingly supple actor in such roles as The

Sopr nos shrink to the shrink, Dr Ell ot Kupferberg, and Netflix

recent y released a comp eted version of We less long unfinished The

Other Side of the Wind, in which Bogdanovich, n the th ck of his 70s

success, played a version of himself named Brooks Otter ake, a role

Wel es wrote to explore the fraught Oedipal themes of their own

relationship Now 79, Bogdanovich s noticeably frail as he recovers

from a fa l he suffered while at a French film festival, where he col

lected a lifetime achievement award; he shattered his

emur

We talk at a cluttered dining room tab e n the modest gr

floor

To uca Lake apartment he shares with his ex w fe Loui

ratten

and her mother Mid interview, a diminutive, grandmotherly

woman with a Dutch accent sneaks behind him through the tight

dini

oom on her way to t

itchen Bogdanovich mot

at my

copy

he Killing of the Un

n, the book he wrote abo

e 1980

mur

of his then girlfrien

layboy Playmate Doroth

ratten,

Lou

s ster Hide that bo

ill you? he requests Th

Doro

thy s mother Nelly Hoogstraten appears several more times to de

liver h m pi ls, to ask if he d like her to make coffee, to see when he d

like h s dinner Thank you, darl ng, he answers every time

Photograph by Robert Maxwell

founded in the midst of the Reagan Revolution, not exactly a propitious moment for

any left-wing group—reformist, revolutionary, or otherwise. Harrington deserves a

little credit for creating what proved to be

the institutional base for today’s muchexpanded DSA. Moreover, what is behind

DSA’s recent growth, if not a variant of

operating as the ‘left wing of the possible’? Isn’t that what Bernie Sanders repre-

sents? And Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez?

They are working within the Democratic

Party to push it leftward.”

Chicago journalist Alex Kotlowitz

revisited a murder that exemplifies

why so many violent crimes go unsolved in

the city (“Ramaine Hill Bore Witness,”

March 4–17). J. Brian Charles called it an

“amazing read … on an unsolved murder in

Chicago and why the witnesses won’t testify. It’s not some code of the streets; it’s

fear,” and Gus Christensen added, “This is

a solvable problem in the richest country

in the world!” UCLA law professor Adam

Winkler wrote, “Kotlowitz’s harrowing

2

account of gun violence in Chicago highlights the absurdity of the NRA’s favorite

shibboleths, like ‘A good guy with a gun is

the only thing that can stop a bad guy

with a gun.’ By using guns to silence and

intimidate crime victims and witnesses,

the bad guys ensure that lawlessness rules

a community. People know they will be tar-

geted if they testify in court and, as a result,

only one in four murders in the murder

capital of the country is prosecuted. Police

know who most of the killers are. But without cooperating witnesses, the wheels of

justice simply don’t turn. The community

profiled by Kotlowitz’s insightful and reveal-

ing article may best be described by another

adage about guns, this one from the Wild

West: ‘The only law that matters is the law

you carry on your hips.’”

Peter Bogdanovich, that notorious

director of Hollywood’s last golden age,

held nothing back in his interview with

Andrew Goldman (“In Conversation: Peter

Bogdanovich,” March 4–17). Bill McCuddy

tweeted, “This you gotta read. Cher can’t

act. Burt Reynolds is a prick. The list goes

on. Really terrific. And sad in a few spots.”

Channing Thomson said, “This is fascinating. He made a handful of great movies

in the 1970s, but he strikes me as being an

odd personality who hindered his own success through word and deed.” And Philip

Concannon wrote, “There’s an Odd Couple–

3

style sitcom to be made about the time

Orson Welles spent living in Peter

Bogdanovich’s house.” Other readers were

less charmed. @TheIndieHandbk tweeted,

“Bogdanovich comes across as something of

a scumbag in this interview, as do at least

half the people he talks about. And all I

can think is, Man, maybe the people of

Hollywood deserve each other.” Susan

Braudy took issue with the director’s characterization of his ex-wife and collaborator

Polly Platt: “I arranged to meet Platt in the

late 1980s partly because so many of my

Hollywood friends told me she was instrumental in the making of Bogdanovich’s

early and best films. If Platt had outlived

him, she would be much kinder about their

collaboration. The record speaks for itself:

Bogdanovich did his best films working

with her.”

L Send correspondence to

Or go to nymag.com to respond to individual stories.

THE PRIDE

OF BROADWAY

©Disney

LET IT

MOVE

YOU

lionking.com

PHOTOGRAPH: MARVIN ORELLANA/NEW YORK MAGAZINE

inside: How will the Trump presidency end? / Ta-Nehisi Coates on reparations and 2020

The Swamp:

Olivia Nuzzi

Trump’s Rolodex

His phone friends

may be more important

than his staff.

What’s that about?

shortly after news broke this month that Bill Shine would

resign as the White House communications director and deputy

chief of staff, a person knowledgeable about his decision told me

the former Fox News exec had come to understand the counterintuitive dynamic that defines many of Donald Trump’s relationships: Proximity can be meaningless, as those who have his ear are

often out of his sight. “When you talk to him at night, you’re gonna

have more impact than sitting in a room with six people,” the person said, referencing the president’s after-dark practice of calling

and fielding calls from a vast network of informal advisers.

Trump abides by what I call the “Groucho Marx Law of Fraternization,” meaning anyone choosing to be near him is suspect, while

everyone else gets points simply for existing elsewhere. “He always

kind of wants what he doesn’t completely have,” the New York

Times’ Maggie Haberman once said. “You are never more valuable

to Donald Trump than when you’re walking away from him.”

What explains this social idiosyncrasy? Obvious answers, like

march 18–31, 2019 | new york

9

intelligencer

self-loathing, don’t quite feel complete. But whatever the

psychological cause, the effect is manifest in at least one

thing: his compulsive phone habits. His Rolodex is a Greatest Hits and Deep Cuts composed of (mostly) friends, associates, media figures, and tycoons. Although Trump is known

to call senior members of his staff at all hours, his informal

advisers share a common attribute: They’re not there and,

therefore, they can’t be blamed when things are falling apart.

Their praise sounds less sycophantic and, therefore, more

compelling; the president seems to grant the calls coming

from outside the White House an inherent credibility. They

are also a welcome distraction, a link to his old life in Trump

Tower, when concepts such as “executive time,” a term used

by aides to make it seem like the president is doing something productive when he’s fucking around and calling TVshow hosts to gossip about ratings (a subject of intense interest for him, even now), were irrelevant.

Over the last two years, current and former officials from

his campaign and White House, as well as his friends and

acquaintances, have provided information about Trump’s

Rolodex to New York. One source almost literally provided

a Rolodex, sharing an internal document from the Trump

Organization with contact information for 145 employees

and 26 individual departments within Trump Tower. In the

White House, a similar document exists: The switchboard

operators maintain a list of cleared callers, a few dozen outsiders whose contact with the president was sanctioned by

Trump’s second chief of staff, John Kelly. The list includes

Eric Trump, Don Jr., Sean Hannity, Stephen Schwarzman,

Rupert Murdoch, Tom Barrack, and Robert Kraft.

And then there are the unsanctioned callers. Outgoing

calls from the Oval Office or the residence are unregulated,

learned of only after the fact from the call logs kept by

switchboard operators, while those to and from Trump’s

cell phone are unknown—a mystery to the official staffers,

who long ago abandoned any hope of controlling who the

president speaks to when they’re not around. And mostly

they’re not around. Those who couldn’t call the president

directly often went through Hope Hicks, Trump’s trusted

communications director, until she resigned last year.

Often, information has come through Rhona Graff, the

longtime gatekeeper of Trump Tower, who has served as a

channel for those seeking to quickly get a message to the

president outside the official communications structures.

As Roger Stone told the journalist Tara Palmeri in 2017,

Graff was the route for “anyone who thinks the system in

Washington will block their access.” Others to endorse this

plan? Gristedes’ John Catsimatidis.

Last month, Trump’s former personal attorney Michael

Cohen testified before Congress and confirmed that “Mr.

Trump” doesn’t email or text. In 2014, the journalist McKay

Coppins wrote that Trump still used a flip phone “because

he likes how the shape places the speaker closer to his

mouth.” But by the time he was running for president, he

possessed both an Android and an iPhone, from which he

lobbed countless tweets and instigated international news

cycles. In Team of Vipers, Cliff Sims, a staffer on Trump’s

campaign and in his West Wing, described how, on Election Night 2016, as everyone else anxiously watched the

returns, Trump was “casually” accepting calls from random

numbers and, at one point, yelled out for someone to “get

Rupert on the phone” (Murdoch later called to congratulate

Trump, who told him, “Not yet, Rupy,” according to Sims).

The first time I walked through the West Wing, a few weeks

10 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

The President’s

Party Line

“The vast

majority, he just

picks up,” a GOP

senator who

regularly

cold-called the

president told

the Washington

Post. “If he

doesn’t … he’ll

return them

within an hour.”

after Inauguration Day, I was confronted by a large photo

of Trump talking on his unsecure Android hanging in a

stairwell. He continued using unsecure personal devices,

allowing Russia and China to spy on his calls, according to

the New York Times. (In response to the report, Trump

tweeted, “I only use Government Phones, and have only one

seldom used government cell phone. Story is soooo wrong!”)

Most profiles of Trump since the 1980s have featured a

description of him making a phone call or a phone conversation between the writer and the chatty subject. Marie

Brenner, in her seminal portrait of Trump’s Chumbawamba

era, “After the Gold Rush,” said one such conversation went

on for two hours. My first interview with Trump, in 2014,

was by phone, which isn’t in itself unusual; lots of interviews happen that way. What was unusual was how much

of Trump came through the receiver, a level of comfort that

suggested he was picking up a conversation with someone

he’d known for years rather than not at all. Normally, distance can create a barrier, but with Trump, it’s almost like,

by removing the distraction of his physical being, he can

become something approaching human. I wrote then that

his voice conveyed a surprising sadness.

In February, Axios obtained three months of Trump’s

unofficial daily schedules, revealing that for a staggering

average of 60 percent of each workday, or the period

between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., the president engages in “executive time.” But what happens after 5 p.m.? The president

usually leaves the Oval Office around seven. His dinners

rarely take place “off campus,” meaning off the White House

grounds. By eight, he’s watching Fox News in the residence,

and by the time Hannity ends, at ten, he’s on the phone,

often with Hannity himself, or with one of the other members of his external cabinet, or with just anybody else he

feels like talking to. Politicians in Washington—and their

family members—have spoken about receiving calls from

the president with almost alarming frequency. So many

calls that they interrupt woodchopping or interactions with

constituents or, in the case of one call between Trump and

Mitch McConnell, a Nationals baseball game. Trump will

call if he sees you on TV and likes something you said. Or if

he sees you on TV and hates something you said. He’ll also

call to try to change your mind or to try to get you to change

someone else’s mind. Or to chitchat about golf. “I just feel

comfort in calling President Trump,” Senator John Barrasso

said to the Washington Post. Lindsey Graham told Mark

Leibovich this is the most contact he’s had with any president. And Graham is still answering the calls, even though,

during an antagonistic period, the president once read Graham’s private cell number aloud onstage at a rally, forcing

Graham to change his number.

Former staffers, whom Trump rarely banishes completely

from the outermost sphere of his orbit, have told New York

about receiving unexpected evening calls from their old

boss. One former campaign official said that, after not hearing from him for months, the president rang to ask if it was

a good idea to send a certain tweet. The ex-official said he

had the impression everyone else had told Trump no and he

was searching for someone who might tell him yes.

One person who has received late-night calls from the

president told me this: “If you’re Trump, the last thing you

want is a moment of self-reflection. That’s why he’s constantly on the phone at night. Everybody’s afraid of themselves. People fear silence because they don’t want to hear

■

voices. But Trump really fears that.”

WelleCo SUPER BOOSTER

Detoxifying

Liver Tonic

Formulated to boost the

liver’s natural cleansing

and detoxifying processes.

Helps to maintain liver health / Supports healthy

liver function / Helps to reduce free radicals

formed in the body.*

39 ¹⁄₂ Crosby St, NY, NYC

welleco.com

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

Malte, 30, Nolita

After the second

term, he might

face justice.

Think he’ll win

reelection*

Leslie, 54, Soho

He’ll run but won’t be

elected. Maybe

he’ll resign and Pence

will become president

for ten minutes

and pardon him.

Mindy, 23, Midtown East

Loses the 2020 election (wins the

primary). Closely gets impeached but

voted down by Congress.

Jezoen, 48, Upper East Side

americans come

to their senses.

Jonny, 24, Flatiron

His broken presidency

will have motivated

high voter turnout. Several

decades from now, he

will be the reason our ys em

shifts aggressively left.

100-Person Poll:

How Will the Trump

Presidency End?

intelligencer

%

Simona, 21,

Bushwick

Runs again but

doesn’t win.

Has a breakdown

on Twitter.

Rajendra, 21, Elmhurst

I doubt that America

will make the

same mistake again.

Jess, 31, New Jersey

unless the

democrats

can come up with

a really

great candidate.

Myliyah, 22, Bushwick

The optimist in me

say he gets impeached,

but then we’re left

with Pence, which

worries me because he

ctually knows

about government.

Realistically, he runs

again but doesn’t win.

Susan, 21, Lower East Side

I wish he

could be dragged

out of the

country right now,

but most likely

he will run again

and lose.

Think he’ll run

again and lose

in 2020

%

With Nancy Pelosi recently taking impeachment off the table—leading to consternation

among some Democrats—and the completion of the Mueller investigation looking

imminent, the question of how Trump’s presidency will and should end has never been

more contested, and more unknowable. We canvassed 100 people on the streets of New

York—at the Oculus,Washington Square Park, and Union Square—to find out how they

thought this would end. Here’s what they told us. interviews by kelsey hurwitz and yelena dzhanova

Samuel Moyn Yale professor | Donald Trump is likely to lose if he makes it to November 2020—and everyone on both sides of the political spectrum should want him to do so. Not only is it

12 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

Allan Lichtman American University professor | In a Washington Post interview on September 23, 2016, I predicted Donald Trump’s victory, using my forecasting system. I also

d our daughters.

predicted Trump’s impeachment. I stand by that prediction.

critical for the people themselves to throw Trump out of office, but getting him out some other way will reinforce suspicions that “the deep state” and elite forces rule in the place of democracy.

march 18–31, 2019 | new york

13

Yasmeen, 18,

Jamaica, Queens

truly feel like

he will be

impeached.

New York Magazine writer

Frank Rich

New York Magazine writer-at-large

A mix-and-match of the Nixon and

to erode Trump’s support, already

Mueller report will be worse than

we can imagine and will continue

and in all likelihood spend his

golden years in prison. The

certainly be criminally indicted

I no longer believe Trump will

resign, as I long believed he

would. At this stage, if Trump

leaves office, he will almost

Ghostwriter of The Art of the Deal

Tony Schwartz

by laziness and lies about the

wall. Massive opportunity

squandered. From now on, it will

just be photo ops and depositions.

As for the Donald Trump

presidency, it already ended, killed

I assume you’re referring to some

future Barron Trump presidency.

Columnist

Ann Coulter

of luck to his successor, President

Elizabeth Holmes.

2024, with a peaceful transition

of power. He wishes the best

Kristina, 29, Soho

This is unknowable, but my

sense is that the likely outcome

will be, in descending order:

(1) He’s impeached but acquitted

and wins reelection; (2) the 2020

election is close, the Democrat

wins, but Trump insists he

won anyway, won’t quit, leading

to federal marshals removing

him from White House amid civil

unrest; (3) a catastrophe in

foreign or domestic policy (like,

say, Katrina or Iraq) breaks

the base; (4) he loses badly to

New York Magazine writer-at-large

Andrew Sullivan

If Donald Jr., Jared, and/or

Ivanka get indicted, there is a

remote chance Trump could

resign in a deal to spare them.

However, that would be an act of

selflessness—something Trump

hasn’t evidenced in his first seven

decades on earth.

whichever Democratic candidate

wins the nomination. One caveat:

the worst of any modern

president, and he will lose to

Stephen, 64,

midtown

He’s over the

pressures.

The end, in descending order of

probability: (1) Walks away January

20, 2021, as Democrat takes oath of

office; (2) dies or resigns owing to

health; (3) walks away January 20,

2025, after serving eight years in

office; (4) resigns after cutting deal

to avoid prosecution.

New York Magazine columnist

Jonathan Chait

a better shot at reelection if

Democrats and the media obsess

about his daily outrage, most

recent tweet-insults, and his

personal corruptions and offenses.

we expose how Trump is serially

betraying the very people

he claims to champion.He has

The Trump presidency ends when

he’s voted out of office in

November 2020. But for that to

become a reality, it’s vital that

cuts, Federalist Society–approved

judges, etc.—within Trumpism.

The welfare chauvinism, mutant

nationalism, and Idiocracy-style

rhetorical cretinism are here to

stay as items of public consumption, even if the old tax-cutsand-tax-cuts Republican agenda

remains dominant. This will

be the case irrespective of what

happens to Trump, who has

only shown himself to be what

we knew him to be: the

opportunist nonpareil.

learned that they can pursue

their top policy priorities—tax

dragged off in irons, or humiliated in 2020. What seemed to be

an anomaly in 2016 has proved

to be a revelation. In the same

way that Trump understood

he could run what amounted

to a third-party campaign within

the GOP, Republicans have

In an important sense, the

Trump presidency is not going to

end—even if he is impeached,

Author of The Smallest Minority

Kevin D. Williamson

Robert, 33, Chelsea

After Trump learns that the

recently submitted Mueller

report includes his (scandalous)

tax returns and damning

information about his family’s

and the Trump Organization’s

finances, Trump abruptly

resigns (via Twitter, of course).

Jack, 45, Greenwich Village

Loses next election

and claims

election is hoax. Needs

to be removed.

Jordan, 38, Bushwick

Not sure; he hurts my soul.

Ryan, 21, Washington Square Park

Editor and publisher of The Nation

Katrina vanden Heuvel

a currently nonexistent

Democratic candidate.

Think he’ll

resign

Think he’ll

become a despot

1%

%

even bother

running

% Think he won’t

Have no

idea

%

Trump runs again

and wins, based off of wild

MAGA diehards

and Russian interference

… again!

Heidi Heitkamp Former U.S. senator | The Trump presidency will end in January 2025 unless we unite behind a vision of civility to and equal opportunity for all Americans.

The Trump presidency ends, in

Brian Feldman

drip of indictments, congressional

probes, and state investigations

will mean that his approval ratings

stay flat. He will run again because

Trump’s gonna Trump. This is all

subject to several frightening open

questions, however: Will there

indeed be free and fair elections?

Will this president accept the

result of those elections? And will

Democrats resist the urge to eat

their own faces off?

I believe that Trump will run again

in 2020 and lose. The slow drip-

Slate legal correspondent

Dahlia Lithwick

Agnew templates may apply.

If Trump is made to believe by

federal and state prosecutors and/

or Robert Mueller that he, his

business, and/or his crime family

face terminal legal consequences

the moment he leaves the White

House, he’ll make a deal to save

his ass (if not necessarily Donald

Jr.’s or Jared’s), declare himself

a winner, and fade into house arrest

at Mar-a-Lago as part of the grand

bargain. If the Vichy Republicans

en masse are made to believe

that the 2020 polls are their

obituaries foretold, they may finally

man up to help grease the skids.

We also asked 14 pundits, journalists,

academics, and activists to weigh in on how they see the

r

inistr tion en in

Think he’ll be

impeached and

convicted

%

in 2020 and have to

be deposed.*

% Think he’ll lose

It does not end—he changes the

laws and becomes dictator

with inspiration from his idols

Kim Jong-un and Putin.

*(2 OF THEM THINK HE’LL FLEE TO

RUSSIA AFTER HE’S DEPOSED)

Stacey, 35, Queens

Hopefully it

will just end.

Like Brexit.

What the Professionals Say...

P H OTO G R A P H : M A R K P E T E R S O N / R E D U X

Gina, 23, Greenwich Village

The Cheeto-head angers

a militia of people

who then try to attack

him. In the end he flees

the country to Russia.

Julius, 64, Jersey City

Best president I’ve

ever seen. His

administration knows

the problems of

America and the world.

Americans will suffer if

they don’t follow

him. He’ll be reelected.

Natalie, 20, East Harlem

*(1 THINKS HE’LL

DIE DURING HIS

SECOND TERM)

Cecile Richards Former Planned Parenthood president | The same way it started: with millions of women coming together to demand better for ourselves a

MORE PREDICTIONS

He’ll probably get reelected

and die halfway through.

He’s old and sucks.

beyond the capacities of my imagination—as was its commencement.

Patricia J. Williams Columbia Law School professor | I conceive of my work as facilitating a system of governance by rules. Alas, we live in unruly times. The end of the Trump presidency is thus

intelligencer

Politics:

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Is an Optimist

Now

A conversation

about race and 2020.

By Eric Levitz

14 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

What do you know about American politics today that you didn’t know on the day

Donald Trump was inaugurated?

I think I underestimated the left’s

response to Trump. I definitely underestimated the Democratic Party’s response.

I get this rap for being pessimistic, but it’s

inspiring to see. It’s really inspiring to see.

You can certainly see that movement in

how mainstream Democrats talk about race

and

ns of criminal justice.

Tha

oe Biden and Kamala

Harris are two of the leading contenders

for the party’s 2020 nomination—both

politicians who embraced some version of

“tough-on-crime liberalism” earlier in their

careers. Is it possible for them to earn the

votes of those who value racial justice?

Let me start by stipulating that I’m

always gonna be the guy that did not think

we would have a black president in my

lifetime. You need to take that into consideration when you hear any sort of prognostication from me.

That said, Biden and Kamala are different. Biden is really popular right now among

black voters, but it’s worth remembering

that Hillary Clinton was really popular

Photograph by Cole Wilson

among black voters early in ’08, too. And I

think Biden has more than just criminaljustice baggage when it comes to race.

I do think the implicit point you made

about there being a separation between

African-American voters and AfricanAmerican activists is a real thing. I was very

concerned about how Obama addressed

black audiences during his time as president. But I don’t think it ever hurt him in

any sort of demonstrable way. And I think

there’s a similar thing with Kamala: The

idea of threatening mothers of kids who

miss school with jail, under the notion that

you ultimately want to help them? That’s

really, really chilling.

But whether black voters will be concerned about it, though—I am not yet convinced that voters are gonna be as concerned

about it as I would like them to be. But then

I never thought reparations would be on the

Democratic Party’s discussion table, either.

On that point: Democratic presidential

candidate Julián Castro has come out in

support of reparations and promised a commission to study the best approach. Many

progressive commentators have insisted

that that doesn’t count.

When I say I am for reparations, I’m saying I am for the idea that this country and

its major institutions have had an extractive

relationship with black people for much of

our history, that this fact explains basically

all of the socioeconomic gap between black

and white America, and that, thus, the way

to close the gap is to pay it back. In terms of

political candidates and how this should be

talked about and how this should be dealt

with, it seems like it would be a very easy

solution. It’s actually the policy recommendation I gave in “The Case for Reparations,”

and that is to support HR 40. That’s the bill

that says you form a commission; you study

what damage was done from slavery and

the legacy of slavery, and then you try to

figure out the best ways to remedy it. It’s

pretty simple. I think that’s Nancy Pelosi’s

position at this point.

There’s a whole line of thinking that says

the recommendation for a study is somehow like a cop-out or weak. I don’t really

understand why that would be the case.

Look, if you have a sickness, you probably

start with a diagnosis.

White supremacy is a suite of harms

operating on multiple levels across the

board. In the piece, I was dealing with

redlining. Criminal-justice questions come

to mind. There are education questions,

there a

s.

What

t

up and

years of damage. And there are small-d

democratic reasons for why you should be

starting with a study instead of a plan. Have

you talked to the community? Has the community thought much about it? Has there

been much interaction with the community

about how they would like to be paid back?

Allow me to play white moderates’

advocate. The strongest version of their

argument, in my view, goes something like

this: It is very difficult to pass laws that massively redistribute resources from those

who have a lot to those who have little.

The first thing I would say is that the perspective you just outlined—it’s not new. It’s

basically been the white liberal approach to

race and to black America literally since

emancipation. People forget, for instance,

that the Freedmen’s Bureau was not just

some sort of racial set-aside; they actually

had to do it for poor whites also. So my basic

answer to that is quite simple: When I look

at the track record of programs enacted in

that way, it is not heartening to me.

What I’ve found, particularly in studying

New Deal policy—but not just New Deal

policy—is that people are not fooled by the

fact that you’re trying to close the racial gap

by including more people or doing it in such

a way as to not explicitly say “black.” They

know your motive, they know your aims,

and they oppose it exactly in that manner. I

mean, that was Obama’s approach for eight

years. The folks who voted for Trump

weren’t fooled by it. They weren’t fooled by

the fact that Obama employed this “rising

tide lifts all boats” rhetoric.

That’s the one part of your argument

I’m not sure about. Without question,

reactionary forces have leveraged racism

to try to defeat, undermine, or racially

circumscribe universal programs—and

they’ve often had success. Yet in 2017,

Social Security single-handedly lifted 1.5

million African-American seniors out of

poverty, according to the Center on Budget

and Policy Priorities. Without these benefits, the black elderly poverty rate would

have been 51.7 percent; instead it was 19

percent. And Donald Trump can’t touch it.

George W. Bush tried and failed.

Right. But the case for reparations is not

a case against universal programs. It’s a case

against universal programs as the sole, total

solution to this matter of white supremacy.

It’s not a case against the social safety net;

that should exist no matter what, right?

Race aside, that stuff should exist. But I

think about my great-grandparents: It’s nice

that, at this point, we have a Social Security

program we would support, but the price of

that was my great-grandparents not being

e. I can’t in my mind

all worked out in the

end. Do you understand what I’m saying?

Absolutely.

That was fucked up how it was passed.

Period. And that doesn’t mean we throw it

out right now, but it means that we’re mindful, going forward, in how we design social

programs. I am deeply scared of any attempt

to close the wealth gap, to ameliorate the

broad socioeconomic disparity in almost

every field between blacks and whites in this

country that avoids talking about why those

disparities are there to begin with.

I take it you’re not 100 percent satisfied

with the way Democrats are talking about it.

You know, I am not shocked or even disappointed when those moderates basically

use “rising tide lifts all boats” rhetoric to

address race. But part of why I always considered myself a product of the left was

because that was the place where you could

try to reimagine society. And in 2016, we

had the most serious left-leaning presidential candidate I’d seen since I was a kid and

Jesse [Jackson] ran. But I have to say,

unlike in Jesse’s campaign—which supported reparations—there isn’t the same

level of consciousness of that history in

Bernie Sanders’s.

And to see a candidate like Senator

Sanders just hand-wave reparations away

like it’s nothing, who says, “I think there are

better ways of dealing with this than writing a check.” There’s nothing wrong with

writing people checks! Especially to those

who have had their checks taken from

them. Let’s start there. So it’s hard to have

a left-wing candidate who is pushing the

boundaries on almost everything else, but

when it comes to race—I have a hard time

distinguishing his policies from Obama’s.

None of this makes Bernie a racist, and

none of it is an endorsement of the unspecific, vague reparations talk I’ve heard from

Kamala Harris. But I think it’s fair to question whether Bernie, and more importantly

the people around him, even understand

the illness they think they can treat through

class-exclusive solutions.

There are left-wing critiques of reparations that I appreciate. But the point of

reparations is to destroy white supremacy, not displace its emphasis, not integrate black people into its most acquisitive functions. It’s to question and assault

the entire paradigm.

It seems to me that what might set you

apart from both moderate and Marxist critics of reparations is actually your optimism—

about what’s possible in a democracy or

what storytelling can make possible.

I just don’t have another choice. I just

don’t have another choice. I don’t know how

I go and look my mom in the face. I don’t

know how I go and look my son in the face

and ask him to accept permanent second■

class citizenship of black people.

march 18–31, 2019 | new york

15

Stacey

Abrams,

?

Governor (The job she wanted most.)

Senator (The job Chuck Schumer wants her to run for.)

Veep (The job another white guy might want her for.)

President ( )

The Georgian who is usually sure about everything

finds herself conflicted about her future.

By

rebecca traister

16 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

Photograph by Dan Winters

podcast Why Is This Happening?, sold

out immediately after it was announced,

and in the hours before it starts, tickets

are going for hundreds of dollars on the

resale market. Abrams can see her excited

fans, but they can’t see her.

The hush isn’t unfriendly—she pulled

me off the street into the car, after all—

but it is disconcerting, simultaneously

intimate and slightly awkward. I’m dying

to ask some questions in these extra,

unscheduled minutes I’ve been granted

with my subject, whose time these days

is extremely limited. But I’ve known

Abrams for a few years; I’ve been in her

company often in recent months; I’m

familiar enough with the vibe in the car—

the “We’re being quiet now” vibe—that I

know better than to break the silence.

This is the same Stacey Abrams who, a

few weeks earlier, had deployed her winning gap-toothed smile and rousing rhetoric to break the curse of wretched State

of the Union responses. Her speech following the president’s was so effective

that even Fox News analyst Brit Hume

grumbled that she was “a person with a

lot of presence, [who] certainly speaks

very ably and well,” while his colleague

Chris Wallace noted that, in contrast to

network fave Donald J. Trum

e

seemed to get more to what peop

are like in the reality.”

Since concluding her 2018 campaign to

be Georgia’s governor—refusing to con18 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

cede in a race marred by voter-suppression

tactics and won by Republican Brian

Kemp, Georgia’s former secretary of State,

who’d held on to his job managing the

election despite being a candidate in it—

Abrams has been busier than ever. She

and her team have filed a federal lawsuit

and launched an organization called

Fair Fight to challenge Georgia’s entire

electoral system; Lauren Groh-Wargo,

Abrams’s former campaign manager and

the CEO of Fair Fight, has compared the

suit to Brown v. Board of Education in the

scope of the injustice it aims to remedy.

Abrams has also recently published a

widely circulated essay about identity

politics for Foreign Affairs; shared a

stage with Ava DuVernay in California;

appeared in an ad touting Fair Fight during the Super Bowl; and been a guest on

Late Night With Seth Meyers, BuzzFeed’s

AM2DM, and NPR’s Wait Wait … Don’t

Tell Me! On March 26, Picador will publish a new edition of her memoir–slash–

advice book, Lead From the Outside.

Everywhere she goes, she is surrounded

by people pulling at her sleeve, asking for

selfies, some trembling with nervousness,

some hollering “You’re my governor!”

across airport waiting areas. I heard one

woman exclaim, backstage at Late Night,

“I can’t wait to vote for you for president!”

Then there are the instances, as at the

Power Rising Summit for black women in

New Orleans in February, when a large

audience simply begins chanting, without

specificity, “Run, Stacey, run!”

Back in the car, Abrams takes an audible breath before opening the door and

greeting the whooping crowd with a

smile. That wordless transition between

private and public existence distills one of

Abrams’s many contradictions: She is a

serious introvert, yet her work requires

glad-handing extroversion; she is excruciatingly aware of the electoral challenges

that face her as a black woman who grew

up what she calls “genteel poor” in rural

Mississippi, yet she pushes forward politically with the drive and confidence of a

white man; she devours romance novels

and soap operas, yet she is also a sciencefiction, math, and tax-law geek; she can

come off as one of the most relatable politicians out there, yet she is a total egghead

who drops million-dollar vocabulary

words, once sending me to the dictionary

to confirm what panegyric means (I

mostly got it through context!). And she

is a woman who, having just run in a historic election that many of her fellow

Democrats expected her to lose, is now

being counted on to win, and perhaps

save her party, by prevailing in an equally

difficult Senate contest, or maybe the race

for the presidency. The deepest irony, of

course, is that what Abrams wants to do

is fundamentally rebuild the electoral system that failed her, just as the system

itself wants to pull her in.

P R E V I O U S S P R E A D : M A K E U P BY PA U L E T T E CO O P E R

am sitting in a car with former Georgia

House Minority Leader and recent gubernatorial

candidate Stacey Abrams. She’s just invited me in

from the cold outside Manhattan’s Gramercy

Theatre—where she’s soon to go onstage for an

interview with MSNBC’s Chris Hayes—but

Abrams is signaling in some ineffable way that

she’s not in the mood to talk. She’s checking her

phone and, every once in a while, peering through

the tinted windows at the long line of people hopping up and down in the February chill and in

anticipation of seeing her. The event, for Hayes’s

abrams’s penchant for silence may

occasionally make her seem sphinxlike,

but she is mischievous and wry with those

close to her. Once, one of her staffers and

I were marveling at the vast menagerie of

taxidermied animals at a gas station we’d

just left, when Abrams interjected, “They

stuff everything, including what you hit

with your car. Welcome to southern Georgia: Waste not, want not.” Backstage at

Late Night, I watch her fussing with her

special assistant, Chelsey Hall, about

what to wear on-air. Hall, whom colleagues describe as “basically Huma,”

presses her boss, 16 years her senior: “Stacey Yvonne Abrams. Put. It. On.” Abrams

grumps off to change.

Many have used the phrase “real deal”

to describe Abrams. “Donald Trump is

the warm-up act for the real deal: Stacey

Abrams,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck

Schumer told the press in advance of her

State of the Union response. Afterward,

billionaire Democratic donor Tom Steyer

picked up the thread, tweeting, “Stacey

Abrams is the real deal.

Now everyone in America

knows it.”

The suggestion that

there is something inherently real about Abrams is

worth its weight in political gold in a media environment where the murky

assessment of authenticity

has become a precious

commodity that few

female candidates are

thought to possess. As a

45-year-old black woman,

she’s certainly part of the

real Democratic base:

African-American women

have long been the most

reliable Democratic voters

and organizers, though

you wouldn’t know it from

how rarely their priorities have been

addressed by party leadership, let alone

how rarely they’ve been provided the

financial and institutional encouragement to, you know, lead the party.

But when pundits, and even regular

people, talk realness, they’re talking

optics as much as anything. And some of

Abrams’s traits—her occasional social

stiltedness, her insistence on keeping her

natural hair, her self-described “sturdy”

body type—make her simultaneously

stand out and blend in, at least among

those Americans who aren’t used to seeing anyone who looks and sounds like

them up on the podium. “I’m not normative,” Abrams likes to say about herself,

citing her “race and gender and physical

structure, the way I approach things.”

Nonnormative as she may be, Abrams is

an almost old-fashioned Democrat, with

her ideological (and personal) roots in the

civil-rights, labor, and women’s movements. Her parents, a librarian and a

dockworker, both of whom would later get

divinity degrees and become pastors, were

civil-rights activists from Hattiesburg,

Mississippi. As an undergraduate, she was

trained as an organizer at the A. Philip

Randolph Institute of the AFL-CIO; she

gave her State of the Union rebuttal in an

Atlanta union hall.

A graduate of Spelman College, with a

master’s in public policy from the University of Texas and a law degree from Yale,

Abrams worked as a tax attorney and

deputy city attorney for Atlanta before

being elected, in 2006, to the Georgia

statehouse. She assumed the minority

leadership position—becoming the first

even a democratic socialist. Yes, she talks

forcefully about the chasm of economic

inequality in the United States, the moral

bankruptcy of a system that treats poor

people as if they don’t deserve the dignity

of health care or a functional social safety

net. During a Q&A after a Fair Fight rally

in Albany, Georgia, Abrams tore into

what she says is the underlying message

of state Republicans’ opposition to Medicaid expansion: “If you’re too poor to get

health insurance, it’s your fault. That is

not true, and that is not right … We live in

a state that has a minimum wage of $5.15

an hour.”

But while Abrams supports raising the

minimum wage to about $15 an hour in cities like Atlanta, she’d stop short of a statewide increase, explaining that Georgia’s

history of resistance to unions has kept

wages so low that a blanket hike would be

too much of a shock to the economy.

“I’m not going to do class warfare; I

want to be wealthy,” she tells the far-fromwealthy crowd at the Fair Fight rally.

The irony is that Abrams

wants to fundamentally

rebuild the electoral system

that failed her, just as the

system wants to pull her in.

black woman to lead either party there—

in 2011. In the midst of her legal and

political career, Abrams has published

romance novels (under the name Selena

Montgomery) and founded several businesses, including one that made

formula-ready bottles for babies and

another that helps small companies get

paid more quickly by buying their invoices.

Abrams ran on unapologetically leftfor-Georgia stances on gun control,

criminal-justice reform, health care, and

education. But her progressivism isn’t

completely in sync with today’s cuttingedge policy ideas—she’s not a socialist or

“You’ve probably got aspirations about

that too.” Many in the room nod in

recognition.

Where Abrams is the most passionate

is in her willingness to rumble over

remaking electoral systems that are

rigged to deny the country’s most vulnerable their only real route to civic power. It

may not be as sexy as free college, but it’s

definitely radical— and as Abrams likes to

point out, without full enfranchisement,

we’ll never get elected officials who’ll back

policies that materially improve the lives

of people who aren’t well off and/or white.

Even before voter suppression (argumarch 18–31, 2019 | new york

19

ably) kept her from the governor’s mansion, Abrams was obsessed with the question of who was being counted.

In 2013, she founded the New Georgia

Project, a nonpartisan group whose goal

was to reach into the state’s poorest corners to register its more than 800,000

qualified-but-unregistered voters. And it

is those long-overlooked new voters who

get at least part of the credit for her pathbreaking performance in November:

Abrams won more votes than any Democrat in Georgia history.

The success of her long game—despite

her failure to gain the office she sought—

is what has prompted everyone from

Schumer to assorted passersby to offer

their view of what she should do next.

Schumer is pressuring her hard to run

against the vulnerable Republican senator from Georgia David Perdue (she jokes

about the daily calls she’s been fielding

from “friends of Chuck”), assuming that

she has the best chance of nudging the

party along the precarious path to taking

back the Senate.

Meanwhile, activists and commentators

are imagining her role in the 2020 presidential race. During her SOTU response,

former Obama adviser and Pod Save

America dude Dan Pfeiffer tweeted, “Stacey Abrams should run for president.”

There’s also been online rustling about

how Abrams would make the perfect nota-white-guy vice-presidential foil for any

one of the white-guy presidential

hopefuls. Biden-Abrams? Or

how about Sanders-Abrams? On

the Intercept, Sanders enthusiast Mehdi Hasan wrestled with

his guy’s relative senescence by

sketching out a scenario in which

Sanders would agree to serve

only one term and pick as his

running mate Abrams, who,

Hasan pointed out, “is black

(check), a woman (check), progressive (check), and unites the

various wings of the Democratic

Party like no other politician in

the United States.” Check!

Many who’ve known Abrams for years

aren’t surprised by her ascent. The Times

journalist Emily Bazelon, who attended

Yale Law School with Abrams, remembers

one class in which they were “two of the

only women who raised our hands with any

regularity,” and also “that she was

son we all thought had a future i

… Her magnetism and ability were that

evident.” Ben Jealous, the former president

of the NAACP and himself a recent—and

20 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

unsuccessful—gubernatorial candidate, in

Maryland, met Abrams when they were

training to be youth organizers. Last year,

he posted a photo of them together at 18,

recalling that back then “she told me … she

would be the first black governor of Georgia. I told her I believed her.”

That is the job Abrams wanted more

than anything. But it’s the one she can’t

run for right now, which leaves her with

some major decisions to make: Should

she risk the four-year wait for another

shot at the Georgia governor’s mansion?

Try for a Senate seat that was never part

of her plan? Or maybe take a bigger, earlier leap for the presidency, which she’s

unashamed to admit she’s long set her

sights on … just nowhere near this soon.

abrams is the second of six children.

Her elder sister, Andrea, is an anthropology professor in Kentucky; Leslie, just 11

months Stacey’s junior, was appointed in

2014 by President Obama as a U.S. District

Court judge in Georgia; Richard is a social

worker in Atlanta; Walter, who attended

Morehouse, struggles with drug addiction

and has been incarcerated; and her youngest sibling, Jeanine, is an evolutionary biologist who has been working at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stacey taught herself to read chapter

books by age 4, according to her family,

after Andrea got sick of reading to her.

She counts among her childhood favorites

Abrams says the spreadsheet

of goals she started 25 years ago

allowed her to “dare to want.”

books by the Brontës and all of Dickens;

she read Silas Marner at age 10.

“Basically, what kids were forced to

read when we got to high school, I’d read,”

she recalls. Later, she attended a

performing-arts school where she gravitated to chemistry, physics, and math.

(She also took guitar, but retains only the

ability to strum “anything by Van Halen.”)

After a high-school friend gave her a

novel by the black feminist writer Octavia

E. Butler, Abrams developed a passion for

science fiction. She’s a Trekkie who will

authoritatively rank series—“The Next

Generation and Voyager are about even; I

think Voyager is mildly superior, although

Picard is the quintessential captain. Then

I would do Discovery, Deep Space Nine,

and Enterprise. I don’t understand why

Enterprise was a show.” These days, she’s

into Doctor Who, having grown up on the

Tom Baker version. “Right before this

Photograph by Andres Kudacki

Abrams meets with supporters

at the Sonesta Gwinnett

Place in Georgia in February.

campaign started, I was sick and ended

up watching the Doctor,” she says. “Then,

over New Year’s, there was a marathon.

Now I’m watching all the new ones. I’ve

seen seasons three, four, five, six, and I’m

in the second half of seven.” Abrams

watched three episodes of Doctor Who to

chill out the afternoon before she gave her

State of the Union response.

Abrams’s precocity, and her impatience

with the less advanced, wasn’t always

greeted warmly. “I had a tendency to try

to help other children move faster, which

you’re not supposed to do. You’re not supposed to tell them the answers.”

With Abrams I’m reminded, as I have

been in encounters with several other

female politicians in recent years, of the

painful scene from Broadcast News in

which a crotchety old news executive

taunts Holly Hunter’s type-A heroine, “It

must be nice to always think you’re the

smartest person in the room!”

No, Hunter replies with despair: “It’s

awful.”

It was, perhaps, particularly awful for a

black girl in a predominantly white elementary school in Mississippi. “Stacey

may have read on the same level as the

teachers,” her sister Leslie recalls. “And she

wasn’t shy about correcting you. She was

never rude, but she’d say, ‘This is silly.’ It

was: ‘What is the purpose of this finger

paint? When I go home I’m reading Nancy

Drew. So why am I reading Dick and

Jane at school?’ ” Leslie laughs. “But you

couldn’t punish her for being smart! And

she wasn’t a bad child. So the teachers

were like: ‘Will you go do something useful then? Go make copies!’ Stacey made a

lot of copies.” That meant she spent a lot of

time with adults, like her principal, and

less time with her peers, whom she studied with a kind of distant curiosity.

“I was born trying to figure out why

other kids were just playing in a circle,”

Abrams says. “What are you doing in the

circle? Duck, Duck, Goose? What is the

goose supposed to do? You could be organizing; you could be producing products

that are for sale. You have a circle, but how

are you utilizing it?”

As an adult, Abrams made a conscious

decision not to hide (Continued on page 84)

march 18–31, 2019 | new york

21

THE GREAT

POD

RUSH

HAS ONLY

JUST

U

With 660,000 shows and 62 million listeners already,

1

How Podcasts

Learned

to Speak

The once-useless-seeming

medium that

became essential.

BY ADAM STERNBERGH

when you first heard about podcasts, do you remember how excited you

weren’t? Do you recall the first person

who said, “Did you know you can now

download audio files of people talking?”

To which you might have replied, “Talking

about … what?” To which they might have

22 n e w y o r k | m a r c h 1 8 – 3 1 , 2 0 1 9

replied, “About … anything!”—at which

point you realized that podcasts seemed

like radio but more amateurish, which

wasn’t the most compelling sales pitch.

I’m going to guess you’ve listened to a

podcast since then, maybe even a few. And

I’m going to guess that you’ve even become

obsessed with one or two. There are now

an estimated 660,000 podcasts in production (that’s a real number, not some comically inflated figure I invented to communicate “a lot”), offering up roughly

28 million individual episodes for your

listening enjoyment (again, a real number;

yes, someone counted). The first two seasons of the most popular podcast of all

time, Serial, have been downloaded 340

million times. In podcast lore, the form

was born in 2004, when the MTV VJ

Adam Curry and the software developer

Dave Winer distributed their shows Daily

Source Code and Morning Coffee Notes via

RSS feed. Or maybe it was really born in

2005, when the New Oxford American

Dictionary declared podcast the Word of

the Year. Or maybe it was born in 2009,

when abrasive stand-up Marc Maron

started his podcast, on which he interviews

fellow comedians and other celebrities in

his California garage, debuting a disarmingly intimate and bracing style that culminated in a conversation with Louis C.K.,

named by Slate four years later as the best

podcast episode of all time. Or maybe it

was born in 2015, when people realized

that Joe Rogan, a former sitcom star and

MMA enthusiast, had a podcast, The Joe

Rogan Experience, which started, in his

description, as “sitting in front of laptops

bullshitting” and was now being listened to

by 11 million people every week. Or maybe

podcasts were born way back in 1938,

when Orson Welles proved that a seductive voice could convince you of anything,

ERIC ISSELŽE/LIFE ON WHITE

the century’s first new art form is about to enter its corporate stage.